Society

New horizons

Updated: 2011-04-12 08:01

By Wang Chao (China Daily)

Zhang Lei has a bachelor's degree in architecture, but he is yet to design a building. Instead, as part of his job, he visits newly decorated apartments to inspect the heating systems, gas pipes, sewage systems, window glasses and even the air quality in rooms.

|

An instructor (right) at the Guangzhou Suilian Helicopter Training Co teaches a student how to fly a helicopter. Provided to China Daily |

Zhang says that he is not an interior designer or a sanitation inspector, but a property condition inspector at Home-brains, a leading property inspection company in China.

His job is not something that one finds being advertised frequently on job boards or newspapers. Rather they are part of the growing number of odd or niche jobs springing up, thanks to the diverse economy and growing purchasing power.

"It's like a physical examination of the house," says Zhang. His inspections cover nearly 300 aspects, and he can earn as much as 1,000 yuan ($153) for a 100 square meter apartment. For conducting an air quality test, he gets paid an extra 400 yuan.

Demand for professionals like Zhang has risen sharply thanks to the housing boom. But that was not the case in 2007 when he entered the industry as a fresh graduate.

"I did not want to take the usual steps and decided to follow a different path," Zhang says.

But it was not an easy journey, as in 2007 Zhang's company conducted only 10 apartment visits every month. During the last two years demand for such services has risen sharply and the company currently undertakes nearly 200 visits every month.

"People are paying more attention to their living conditions and are not averse to spending more money to ensure that their new homes are safe and comfortable," he says.

New professions are blossoming in China as the traditional job market is getting increasingly saturated. Job seekers are now turning to niche jobs fuelled by the growing penchant for personalized services. Demand for personal and luxury services, skills training and a host of other sectors are also galloping in tandem with China's strong economic growth.

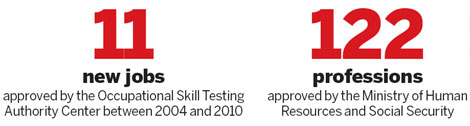

In 2004, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security came out with a list of nine new professions approved by the Occupational Skill Testing Authority Center (OSTAC) affiliated to it. Between 2004 and 2010, the ministry added 11 examples of new jobs, taking the total to 122 recognized professions.

Most of these jobs like locker repairer, jewelry designer and call attendant do not sound strange now, but were perceived as exotic back then.

The OSTAC says that its new job ranking is arrived at after measuring certain parameters. The job should require unique skills, be legal, full-time in nature, and have more than 5,000 practitioners in China, it says.

Experts, however, maintain that there has been a sharp rise in the number of niche and new jobs. By current estimates the number of such jobs is at least 10 or 20 times the figure estimated by the ministry, they say.

"New jobs have been rising exponentially over the years," says Hao Jian, a senior career consultant with Zhaopin Ltd, an online human resources company.

Despite the booming demand, there is not enough talent to fill these positions, Hao says. There are over 1 million jobs in the color consulting area alone, but less than 10,000 people have got the nod to take up these jobs.

Yu Xiaodong, director of the center for public nutrition and development of the National Development and Reform Commission, says that the number of authorized public nutritionists, a new profession approved by the ministry, was only 4,000 in 2010, while in Japan it was over 400,000.

Job portals like Zhaopin have been adding new sections on their websites for niche jobs based on demand. In 2009, it added 20 new categories, whereas by 2011 it grew to 87. Some of the niche jobs that figured in the website were for a video-conference host, personal luxury goods shopper and property condition inspector.

Hao says that there are several interesting trends that explain the rush for niche jobs.

Green jobs have grown nearly 20 percent in the past five years, thanks to the increased environmental awareness. It has also triggered demand for sewage treatment specialists and solar energy technicians, he says.

At the same time there is also a demand in the market for professionals with multiple talents. A fork lift truck driver with stacking skills can earn nearly 5,000 to 6,000 yuan every month at big retailers like Walmart, nearly double the salary of a regular truck driver, says Hao.

"There is also great demand for other professionals like chefs who can speak foreign languages and sports agents familiar with both sports and marketing activities," he says.

Hao says that the underlying factor that is propelling the demand is the rapid personalization of services.

"Employers are looking for more personal services like personal health consultants to design low-calorie family menus; dish-order assistants for those who can never decide what to order in a restaurant; and personal luxury goods shopper to help find the most appropriate Rolex or Louis Vuitton bags," he says.

Guo Haiping is one such personal service provider. He is an authorized pet trainer who works out of his clients' homes. Every day he travels to apartments, villas, lanes and traditional courtyards in Beijing, to train dogs.

"There has always been a misconception that pet trainers trained several animals together in kennels. It is no longer the case," Guo says.

As a professional pet trainer, Guo was the first to start door-to-door pet training services in Beijing. Clients get more personalized services as the trainer trains only one dog during the whole session.

Guo's training has three levels - preliminary, intermediate and advanced. The preliminary training includes walking rules, eating courtesies and other basic commands. The intermediate level involves the same training but for more than one month. The advanced level is usually for kennels to prepare them for pet competitions.

A behavior correction session, or the preliminary training, costs 2,500 yuan, and lasts for two weeks.

With more pet owners seeking personalized training services, Guo earns anywhere between 6,000 to 15,000 yuan every month.

Despite being satisfied with his job as a "personal dog trainer", Guo says that the government is putting up barriers for his new profession.

"Take Beijing as an example. The government does not allow citizens to raise dogs taller than 35 cm, as it may hurt others. Such laws restrict our business. It also reflects the ignorance of regulators. Dogs should be classified by breed and not size," says Guo.

Unlike Guo, Guan Xiwen's services are targeted at the affluent in China. To take his classes, clients need to pay at least 200,000 yuan ($30,600).

Guan is one of six coaches at the Guangzhou Suilian Helicopter Training Company in Guangdong province, that teach people how to fly a helicopter. He is busy most of the time as he has six to seven students to train at a time.

"Soaring like a bird in the sky is something that everyone dreams about," he says. "When people make enough money and are able to afford helicopters of their own, they come to professionals like us for training."

Guan says most of his students take the classes for various reasons. While some come with a desire to learn it as a vocation, there are others who are sent by their employers to acquire additional skills. There are also students who have their own helicopters, but come to classes just for fun, he says.

"Rich people are tired of cars and golf. Flying is certainly much cooler," he says.

Career consultant Hao, however, says that policy constraints are not the only barrier for development of new professions. Lack of industry standards and evaluation systems are other major problems, he says.

"For example, how does one evaluate the performance of a personal luxury goods shopper? How does one know whether or not they are deceiving customers?"

The government should expedite the legislation process for new professions to protect customers' rights and sustain the momentum, he says.

Others like Liu Xiaodong, however, feel that despite the high profit margins, new jobs have innumerable risk factors and unsteady revenue flows.

"Service-based jobs are usually paid by work volumes, or the level of customer satisfaction," says Liu, who has worked in vocational institutes for more than 20 years. "It is quite possible that a new job practitioner can earn a lot on one day and virtually nothing for the next few months."

Hao says that most of the new jobs are service-oriented and involve personal reputation. He feels that it would be difficult for newcomers to compete at the beginning of their careers.

"People going to gyms can often notice this phenomenon as personal coaches with the same experience have different client numbers. Customers search for experts based on referrals from family, colleagues and friends," he says.

Lack of academic and comprehensive training is also plaguing the growth of new professions. Most of the new job practitioners either learn the skills themselves, or get trained at vocational schools. There are very few colleges or universities that offer training in such fields.

"The disparity between higher education and demand has led to a situation where there is no sustainable supply of high-quality talent," Liu Xiaodong says.

Specials

In the swim

Out of every 10 swimsuits in the world, seven are made in China.

Big spenders

Travelers spend more on shopping than food, hotels, other expenses

Rise in super rich

Rising property prices and a fast-growing economy have been the key drivers.