William Daniel Garst

Money is need not greed for Chinese

Updated: 2009-11-27 07:56

By William Daniel Garst (China Daily)

Have Chinese become totally materialistic and mad about money? Is this behavior creating a deep moral crisis even as the country's GDP grows at breakneck speed?

Plenty of dramatic anecdotal evidence exists to suggest that this is indeed the case. For example, last month a young girl from a rich family in Chongqing literally spent millions of yuan to welcome her pet dog home. Earlier this year, officials in a county of Hubei province ordered civil servants and employees of State-owned companies to buy 23,000 packs of the province's brand of cigarettes every year. The edict, which was widely ridiculed and quickly revoked, sought to boost the local economy.

But after living in China for four years, I have learned that it is a very complex place, which belies sweeping generalizations.

If pressed to answer in "yes or no" to the two questions posed in the beginning, I would say "no" for ordinary people, but "yes" for many of the nouveau riche.

| ||||

One big reason for this behavior is that people have to save lots of money for a rainy day, especially medical emergencies. Thus ordinary Chinese strive to make money out of necessity, not to blow it on consumer goods. But thriftiness remains deeply entrenched among the people, especially among the older generation.

For example, after a British colleague moved into a nice big flat in the upscale Seasons Park Complex near Dongsishitiao in Beijing, his Chinese girlfriend told him not to disclose the rent they were paying to her visiting mother, lest she should think they were being overly profligate.

But this frugality does not stop ordinary Chinese people from being generous when it comes to helping those in need. After the Sichuan earthquake last year, I was struck by the large sums our company's lower level employees donated to the disaster relief fund. Chinese colleagues making less than 5,000 yuan a month put hundreds of yuan into the donation boxes. Nothing like this happened in the US after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, something that makes me deeply ashamed for my country.

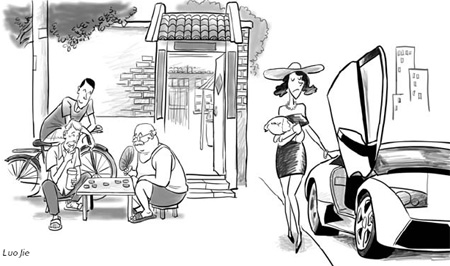

But unlike ordinary Chinese, who continue to save, many affluent people have been bitten by the materialism bug. Evidence of conspicuous consumption can be seen everywhere in large cities such as Beijing. Posh apartments, big cars, particularly SUVs, and other luxury products have become important status symbols for the still relatively small, but rapidly expanding number of "Chuppies" (Chinese young urban professionals).

Of course, other countries that moved from poverty to affluence have also had their share of nouveau riche behavior. Indeed, in the US, it formed the basis of the Thorstein Veblen classic, The History of the Leisure Class.

But what's more troubling for China is that recent US experience suggests this phenomenon could persist even in mature developed economies. The trademark slogan of the 1980s in America was "greed is good", though the Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has described the roaring 1990s as the "greediest decade in history". The greed didn't stop there, either, for from 2003 to 2007, Americans over-leveraged themselves while competing to own the biggest homes on the block.

The American experience contains another warning for China: This materialism has not made Americans any happier. In fact, in international surveys, such as the University of Michigan World Values Survey, America consistently fails to rank among top 20 countries when it comes to happiness (China ranked 46th in the most recent survey).

An important research on happiness done by Richard Layard, a professor in London School of Economics, shows that the income growth in the US, especially after the 1970s, was disproportionate to the rise in the happiness level.

Layard suggests that a crucial piece of this puzzle is the role of socio-economic equality in happiness. In highly unequal societies - socio-economic inequality has recently risen sharply in America - people measure their happiness by comparing their wealth and material possessions against their more affluent counterparts. Happiness is determined by one's ability to "keep up with the Joneses".

But this quest can only lead to frustration. In unequal societies, most of the people, even those who are well off, are by definition relatively less affluent. Thus Layard argues that the happiest societies are closely-knit ones marked by high levels of equality.

This claim conforms to my observation of life in China. The ordinary folks in my old Dongzhimen neighborhood, engaged in very simple and non-materialistic pleasures - adults singing and dancing in Nanguan Park and children playing with their old scruffy toys in hutongs - are among the happiest people I have seen in Beijing. The northern part of this neighborhood remains a closely-knit siheyuan community. Everyone has roughly the same income and living standard.

Over the past three decades, China has taken tremendous strides in reducing poverty. This certainly matters because recent research on happiness also shows that poverty and happiness do not mix. The govern-ment is trying to address China's widening socio-economic inequality by improving access to health care and education, and adopting other social welfare measures.

A good start has been made, but more needs to be done. The success of these efforts will determine the extent to which the Middle Kingdom will be gripped by materialism and craze for money on its way to becoming an affluent economy.

The author is a teacher at Peking University.

(China Daily 11/27/2009 page9)

Specials

President Hu visits the US

President Hu Jintao is on a state visit to the US from Jan 18 to 21.

Ancient life

The discovery of the fossile of a female pterosaur nicknamed as Mrs T and her un-laid egg are shedding new light on ancient mysteries.

Economic figures

China's GDP growth jumped 10.3 percent year-on-year in 2010, boosted by a faster-than-expected 9.8 percent expansion in the fourth quarter.