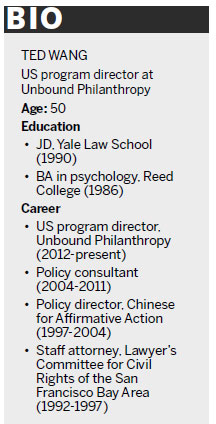

Seeing his Army engineer father wronged, Ted Wang turns activist

When Ted Wang's father filed a lawsuit in the late 1970s against the US government - specifically the secretary of the US Army and former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld - he wanted acknowledgement that he had been wronged.

At the time of the suit, Hung Ping Wang was in the US Army Corps of Engineers as an engineer but in his decade-plus career at the federal agency he had never been promoted despite having plenty of experience in Taiwan and a master's degree from Stanford University in California.

|

|

|

The elder Wang was told explicitly that a promotion would never happen because he spoke English with an accent, and that he could never manage people because of that. Watching his father struggle in his workplace despite being qualified for the job influenced Ted to eventually go to law school and then become a civil rights advocate, focusing on racial injustice and discrimination.

"I witnessed that growing up, and seeing how difficult it was, and how frustrating it was for someone who was intelligent, qualified, had probably more experience than most people in his workplace, to not be respected because he spoke English with an accent," Wang said.

"What became clear when he talked about it was that this was not an isolated experience. All of his former classmates, friends who had come to the United States, had had a similar experience of having their qualifications overlooked because they didn't fit the idea somebody had of a manager: someone who can't speak English perfectly," he said.

Wang immigrated to Oregon from Taiwan and was a teenager when his father filed the lawsuit. In the 1970s, the state was almost completely white, he said, and his family was greeted with hostility where it settled because it was the neighborhood's first non-white family.

"People actually burnt something on our front lawn (during the lawsuit)," Wang said.

"It was a completely different era where people were much more explicit about their biases."

The lawsuit - Hung Ping Wang vs. Martin Hoffman, Secretary of the Army, and Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense - dragged on for years and took a substantial amount of money, Wang said.

Ultimately, the elder Wang lost the suit because no bias or discrimination was found. He was allowed to retire with full benefits in his 40s, but without the promotion he wanted.

"The reason why people file lawsuits is because they want someone to acknowledge that they were wronged. He never got that," Wang said. "He was able to start a successful business, doing construction real estate so I think that took some of the pain away - that he was able to have a successful second career - but I'm sure for a long time, the fact that nobody acknowledged his experience was really painful for him."

|

Ted Wang, program director at Unbound Philanthropy, has spent his entire career in community advocacy, hugely influenced by a racial discrimination lawsuit his father filed against the government when Wang was a teen. Amy He / China Daily |

The younger Wang later attended Reed College, studying psychology before going to law school at Yale University. After law school and with his father's legal battle as an impetus, he began his career in community organizing and civil rights advocacy.

Wang, now 50, worked at the Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights, a national civil rights organization, for seven years when he got out of law school. He then worked at the Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA) organization for another seven years, both organizations in San Francisco, where he moved after college.

"It was the period where I had the greatest personal growth. It was a small organization that we were able to build up over time," said Wang, who is still based in San Francisco, where he lives with his wife and son.

At the CAA, Wang oversaw work on getting immigrants language access, making sure that federal agencies had personnel that spoke a variety of languages and that federal materials and information were printed in different languages as well.

"We were also able to able to get the first language access ordinates adopted in the whole country. It was passed by the city of Oakland and then shortly afterwards, San Francisco, within months," he said. "You actually need really strong advocacy to make sure those are in place. If you don't have political power, you don't have accountability, laws don't get implemented. If you have a general requirement that things become accessible to immigrants, but nobody is looking at it, nobody is thinking about, 'How do I do this proactively?' then it's not carried out in a responsible way. That was the goal of our local organizing."

Now Wang is a program director at Unbound Philanthropy, based in New York with a London office, where he works with organizations seeking to improve the lives of immigrants in the US. Unbound is a small to mid-sized foundation that gives a little under $6 million a year to 45 to 50 US and UK organizations that focus on community building and immigrant advocacy. Wang sees the work as crucial to the growth of the US.

"One priority is to create more welcoming communities at the regional level, to try to help receiving communities understand how immigrants can help them economically and otherwise, and to understand that this country is going through a big transformation in terms of demographics, and that's not a thing we should be afraid of," he said. "It's happening and it will be good to have policies that facilitate better understanding, and programs that actually engage people across communities."

amyhe@chinadailyusa.com