Keeping the 'blood of Turpan' circulating

Updated: 2015-04-16 07:49

By Cui Jia(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Despite being more than 2,000 years old, the ancient karez irrigation system used in the areas around the ancient Silk Road city is still in use. Now, new developments are likely to reinforce the canal's importance, as Cui Jia reports.

Ablimit Yagup watched carefully as his son Ablikim was lowered into a narrow opening in the Gobi Desert near Turpan city in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. The 53-year-old then tied the steel wire around his own waist so he could descend to the bottom of the 30-meter-deep shaft and join Ablikim. From the base of the shaft, the two men entered a muddy subterranean canal filled with slow-running water.

The locals say that what runs in the canal, or karez, which means "well" in the Uygur language, is not water, but the very blood of Turpan itself. People have lived around the oasis settlement for millennia, and merchants, monks and preachers traversing the ancient Silk Road trade route knew the area as an important strategic point for refreshment and replenishment of supplies.

|

Ablikim Yagup works in a karez near his village in Turpan's Shanshan county. The mud and dirt he digs out is carried to the surface in a bucket via a maintenance shaft. The work has to be undertaken around April every year, before the snow on the Tianshan Mountains thaws in the spring. Zhao Ge / Xinhua |

|

Villagers in Shanshan county wash clothes using water from the karez irrigation system. Photos by Zhao Ge / Xinhua |

|

Ablimit Yagup (right) and his son don protective clothing before descending to the bottom of a shaft to remove the mud that clogs the local karez. Photos by Zhao Ge / Xinhua |

Ablimit and his son are following in the family tradition. Like previous generations, their job is to remove the sodden sand that clogs the local karez to keep the blood of Turpan circulating.

"Without the invention of the karez, Turpan, which has prospered under different kingdoms and religions throughout history, simply wouldn't exist," said Chen Xinwei of the Turpan Cultural Relics Bureau, who has been working to preserve the ancient man-made structures, many of which are still in use, despite being built more than 2,000 years ago.

'Fire State'

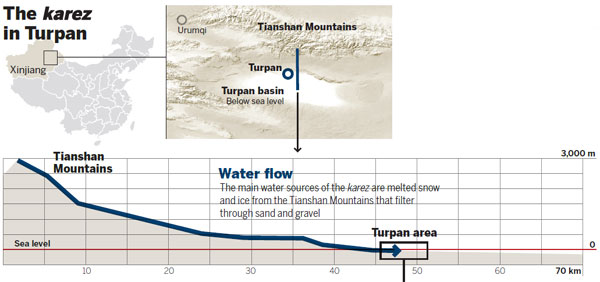

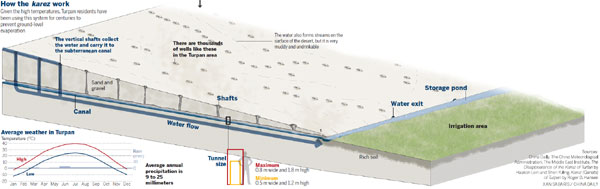

Turpan is the hottest and driest area of China. The highest ambient temperature on record in the area is 48 C, but in the Gobi Desert the surface temperature of the sand dunes can rise as high as 82 C, so it's no surprise to learn that Turpan is known as the "Fire State". The karez irrigation system was developed to prevent water evaporating at ground level.

The karez are fed by meltwater from the Tianshan Mountains. The water is filtered through sand and gravel at the foot of the mountains, before gravity carries it through the karez to the oases that form where the canals resurface. The vineyards nourished by the icy water are said to produce the sweetest grapes in China, and the underground streams provide potable drinking supplies for the local people.

In 2009, a survey conducted by Chen's bureau found that Turpan had 1,108 extant karez, and that 278 of them still carried water. The others have either dried up or have partially collapsed, according to Chen, who added that the shorter karez range from 3 to 5 kilometers in length, while the longest stretch more than 10 km. A small oasis forms at the end of every karez.

The karez nicknamed "Midun" near Ablimit's village in Turpan's Shanshan county is still full of life and acts as a water source for nearby villagers.

Unclogging the karez is delicate work and the basic techniques employed have remained unchanged for centuries, although tractors have replaced donkeys as the motive power to lower people into the vertical maintenance shafts, and battery-powered headlamps have replaced oil lamps to illuminate the dark, dank tunnels. Everything else is done by hand.

The work has to be undertaken around April every year, ahead of the massive volume of meltwater that will flow down from the mountains after the spring thaw. The work is of prime importance to the locals, and it must be done thoroughly to prevent the canal from becoming clogged and blocking the flow of water.

"Midun is not a difficult karez to clean, but some are more than 70 meters deep and extremely narrow, so we have to stoop and work on our knees," Ablikim said. The 29-year-old, who has spent the last 10 years as his father's apprentice, uses the pickaxe-shaped tool, designed for digging mud and widening the canal, that belonged to his grandfather.

He said the work is dangerous because the ancient structures can collapse at any time, and without warning. "It's hard to imagine how many people have lost their lives constructing and maintaining the karez."

Ablikim and his father repeatedly loaded the soggy mud into a basket, which was then lifted up through the shaft. Working together, they can remove 2 to 3 metric tons of mud and dirt from Midun every day.

People who know how to maintain karez have become great assets for Chen's team, which has been renovating the ancient irrigation system since 2009. "We call them 'karez craftsmen' whose skills are passed down from generation to generation. There are many of them in Turpan's villages and they are key for future renovation projects," he said.

So far, more than 600 km of the underground canals have been reinforced, and more than 10,000 vertical shafts have been repaired. Preparations for the renovation of 15 more karez are underway and the work will start later this year, according to Chen.

In addition to government funding, the contractors hired to build the high-speed railway that links Turpan and Urumqi, the regional capital, have also allocated special funds to reinforce karez near the railway link, which came into operation in November, to ensure they will be able to withstand the vibrations caused by the trains.

The openings of the maintenance shafts, which also allow water to enter the canals, can be seen dotted across the Gobi Desert in Turpan. They are a constant reminder to the locals that more than 5,000 km of the "Great Underground Wall of China" lie just below their feet.

Developmental disagreements

The karez system is considered one of China's greatest surviving ancient man-made structures, but experts are unable to agree on who developed the system in Turpan, Chen said.

Some say the technique was passed on by travelers from inland China about 2,000 years ago, while others argue that it was imported from Central or Western Asia, a plausible theory given that karez are also found in Afghanistan and Iran. A third group believes that the local people invented the system as a survival strategy in the Fire State.

Chen, 34, was born in Turpan and grew up drinking water from the local karez. "The karez link the people of Turpan together. People from different ethnic groups meet at the karez and learn about each others' cultures. Sadly, the one I used to drink from has now dried up," he said.

The State Council recently upgraded Turpan's status from prefecture to city to improve administrative efficiency and help accommodate its development as part of the Silk Road Economic Belt, which has been proposed by President Xi Jinping with the aim of improving cooperation with countries in Asia, Europe and Africa.

Chen said the status upgrade is good news, but he is concerned about whether Turpan's extremely limited water resources will be sufficient to support all the development projects. The locals are heavily reliant on borehole water that's pumped to the surface from wells as deep as 200 meters underground, and the area's groundwater resources have been already excessively exploited, he said.

"The ancient karez system is very environmentally friendly because it just collects and transports natural water. We should encourage people to use more karez water. Unlike other cultural relics, such as the remains of ancient cities, human activities are good for the karez. The more people that use the karez, the better the system can be protected," he added.

"These ancient structures were essential to people on the ancient Silk Road, and they can continue to support life on the Silk Road Economic Belt 2,000 years later. How magical is that?"

Xinhua contributed to the story.

(China Daily 04/16/2015 page6)

HK singer-actress Mok takes fans on global journey

HK singer-actress Mok takes fans on global journey

Sandstorm engulfs North China

Sandstorm engulfs North China

Qinghai quake: Reliving the memory

Qinghai quake: Reliving the memory

Father horses around to save his son

Father horses around to save his son

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - April 15

Ten photos you don't wanna miss - April 15

Oil paper umbrellas made in Sichuan

Oil paper umbrellas made in Sichuan

Ex-student sought in shooting death of North Carolina college

Ex-student sought in shooting death of North Carolina college

Women in politics - Hillary Clinton is just one of them

Women in politics - Hillary Clinton is just one of them

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Japan tops China as top holder of US debt

Paulson: US should have joined AIIB

Economic reforms in China are 'needed'

Li Na named Laureus exceptional award winner

Alibaba may face 'blacklist' trouble in US as fakes continue to abound

US to help smart cities

Clinton's win not guaranteed despite global celebrity

US has record number of applications for H-1B tech visas

US Weekly

|

|