Death and glory in the mountains

Updated: 2015-04-22 07:41

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Nearly 80 years ago, Chinese forces resisted the invading Japanese at a small hillside village just outside of Beijing. The soldiers' stories and the sacrifices they made have become an obsession for one resident of the capital, who is determined to keep their memory alive, as Zhao Xu reports.

On April 4, the day before the national Tomb Sweeping Festival, Yang Guoqing stowed two coffins in the trunk of his car and took a 20-minute drive to the hills near his home.

After walking uphill for two hours accompanied by about 40 people, Yang arrived at a piece of land less than 4 meters square.

|

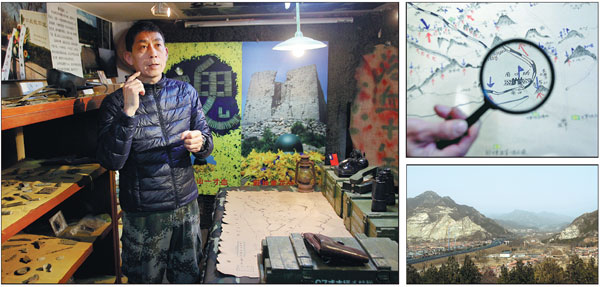

Left: Yang Guoqing, a mountaineering guide from Beijing, displays the exhibits in his small museum. Top right: Yang points out the location of Nankou on a map he drew himself. Bottom right: Yang discovered the site of the battle of Nankou while hiking and camping in the district a few kilometers north of Beijing. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

|

A gas mask Yang discovered suggests the Japanese used poison gas during their invasion. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

|

Corroded bullets Yang unearthed during his numerous trips to the site of the battle. Photos by Zou Hong / China Daily |

"On one side was the Great Wall, while on the other was a steep slope leading to the base of the mountain," said the 52-year-old mountaineering guide, who lives in a northern suburb of Beijing.

"I had discovered two skeletons at that spot a few months earlier, so I took two small caskets along so I could bury the bones."

It was not the first time Yang had hauled coffins up the craggy incline, and he has conducted several memorial services for those who lost their lives in the rocky landscape almost 80 years ago.

In August 1937, fierce fighting broke out between 100,000 Chinese soldiers and the invading Japanese Imperial Army in the mountainous region on Beijing's doorstep. "Further north is the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Historically, conquering armies from the north had to pass through this area before advancing farther south to the country's heartland. That's why the area is called Nankou, which means, 'Southern Mouth', " Yang said.

The situation faced by the Chinese army that fateful summer was one of the grimmest ever faced by a defending force. "The Japanese army had taken Beijing by the end of July (from the south), and now they were pouring in from the north. This meant that any army that sought to defend Nankou would have to fight on two fronts - the south and the north," he said.

"The Japanese army, with their armored fighting vehicles and bomber planes, predicted that Nankou would fall within three days of the attack, but the Chinese defended the village for 18 days, losing 10,000 men and killing about 3,000 of the enemy. After the battle, the Japanese collected the bodies of their dead and burned them, but this is the final resting place of the Chinese soldiers," he added.

Yang also took a trip to the mountains on a chilly, early spring day two weeks before the Tomb Sweeping Festival. The wind whistled through the skeletal branches of the trees where the buds had just begun to show, and the ancient horse trails used by traveling merchants were hidden under thorn bushes.

Except for the occasional tweet of a bird and the crackle of the dry leaves underfoot, everything was silent. That silence speaks evocatively to Zuo Bingde, an 88-year-old who has spent his whole life in Nankou. "I was just 10 when the fighting broke out. Every valley was filled with the deafening sound of gunfire. From our little house, I saw plumes of dark smoke rising up from the mountain ridges during the day, and the gleaming trajectories of the Japanese shells at night," he said.

A dramatic discovery

For many people, the war is just a distant memory, but the village and surrounding countryside hold a fascination for Yang, who grew up in the vicinity and knows the area like the back of his hand.

His obsession with the battle began with a dramatic discovery in 2005, when he was 42. "At the time I was working as a guide for a local mountaineering club. One day, as we were camping on a mountain called Gaolou or 'High-rise', I suddenly spotted an ancient fire tower pitted with bullet holes," he said. "This was at the highest point of the Beijing section of the Great Wall, 1,400 meters above sea level. No one, no thing, could have punched holes in that thick stone wall except bullets fired from a powerful machine gun."

Yang returned a year later, after studying the county records and talking with many elders in the neighboring villages. This time, though, he was accompanied by a few friends and a metal detector.

"Treasure hunters will know how excited we all felt," Yang said. "I remember the first time the detector bleeped, I shouted 'get down' to the others and threw myself on the ground, just in case it was an unexploded bomb or landmine. Later, we got up and started digging, eventually discovering an acid-eaten cartridge case. We were elated, but I had absolutely no idea what was to come - all the heavy things that were about to inundate my mind," he said.

As Yang dug deeper and looked more closely, he discovered a cache of wartime debris. "The stuff was everywhere, cartridges and fragments of bullets and rusted cannons, all separated from us by almost 80 years and a thin layer of soil," he said. "There are bomb craters and small trenches hidden under the bushes. That's where the Chinese soldiers fired as the Japanese charged up the slope."

Yang's quest for history hit a mournful and disturbing note in November 2011, when he spent a night on a snow-covered mountain beside a deep ravine the locals call "The Valley of the Dead". "At one time, the land was strewn with bodies from the fighting. They were later washed down into the valley below by torrential rain," Yang said. "The locals believed the valley was haunted. I decided to spend a night there - not to test the rumor, but to be closer to the war."

Despite his resolve, Yang was terrified when he heard a loud rustling sound shortly after sunset. He stayed awake until the early hours, occasionally venturing from his tent. "When I awoke, the sun was high in the sky, and I discovered boar bristles on the tree trunks just a few steps from my tent. I had gotten myself in the way of a wild boar that had impatiently rubbed itself against the tree," he said.

"The wind was vicious at midnight, scooping up the snow and making every tree branch squeal. It died down later, though, and gave way to an all-encompassing stillness in which the sound of a single leaf falling to the ground was distinctly audible," Yang said. "For me, it was like a replay of the battle - its heated hours and its aftermath."

Yang said the memory is indelible, but not as harrowing as an experience that involved garlic rather than ghosts. "As I dug deeper, I found an iron shovel, and then a teacup and a bowl, both with porcelain enamel. The cup was used to cover the bowl. I opened it gingerly and there it was, a garlic bulb whose inside had rotten away but whose outside was still intact," he said. "Initially, I thought it might have been dropped there by someone, maybe a few years ago. But as I removed the items and dug again with my spade, I discovered a belt buckle, a bullet clip and a tube of toothpaste with Chinese characters that said it had been produced by a manufacturer in Shanghai in the 1930s. All of these things were lying on top of an unused gas mask.

"The Chinese soldiers probably died suddenly while resting in this area away from the main battlefield, overpowered by deadly gunfire, or more likely, by a cloud of the poison gas the Japanese used," he said. "Like a still life painting, those everyday items offered a poignant reminder of the cruelty of war."

Today, the teacup, bowl and gas mask share the same shelf in Yang's small underground museum below his family's tiny shop. "Each shelf is dedicated to a different part of the battleground," he said, scanning his collection of nearly 2,000 items, including cartridges, helmets, hat badges, and in one case, a few shards of bone wrapped in cloth and sealed in a small box. "It's an addiction. Not going there for a few days would be hard for me because I feel those who died there are calling to me, and their stories are still waiting to be told."

Begging forgiveness

Occasionally, he is accompanied by Chinese and expat members of his hiking club, the sons and daughters of men who fought in the battle, or on very rare occasions, the elderly veterans themselves.

"In August 2014, I took a veteran called Jia Shanming to the battleground. By then, he was 97," Yang recalled. "When we arrived at the exact place where he had fought, the old man knelt down and said, 'Forgive me, brothers, for propping my gun on your dead bodies, and for leaving you here for so long.' "

According to Jia, no sand bags were available during the battle, so the Chinese troops had no alternative but to use the bodies of their fallen comrades to prop up their machine guns to prevent them from shaking violently when fired.

Jia, who now lives in Henan province, about 1,000 kilometers from Beijing, carries several scars on his upper left arm, but he doesn't need them to remind him of an experience he will never forget. "When I arrived at Nankou, seven days into the battle, I smelled human flesh and literally had to walk over the dead to reach my position," he said. "The chambers of our machine guns became so hot that the cooling water circulating inside the guns was boiling."

On Aug 8, 2009, four years after he got his first "glimpse of war" at Gaolou, or Hill No. 1390 as it was designated by the Chinese army, Yang and some friends walked to the top of the mountain carrying a 150-kilogram stone stele bearing the inscription, "A Belated Memorial".

"So far, I've erected five memorial stones, and carved inscriptions on three of them alone in the mountains. I hope people who come here for fun will discover the history for themselves," he said, lighting a cigarette and placing it on a rock in front of a stele. "We may never know the names of those dead soldiers, but we owe each of them a deep bow."

It's now nearly three weeks since the Tomb Sweeping Festival, but Yang is still emotionally in thrall to his recent experience. "Most of those who were with me were students from a nearby university. They told me war had never been so real to them," he said. "For me, the heroism of the Chinese army lies not in winning, but in fighting vehemently with little hope of winning."

The two corpses he buried earlier this month were discovered lying face down, one on top of the other. "At first, I thought both were Chinese because after winning the battle, the Japanese collected and burned the bodies of their dead," he said. "But, lodged in the rib cage of one of the bodies, I found a bullet of the type known to have been used by the Chinese Army at the time, as well as a couple of shirt buttons that appeared to have been made in Japan.

"They may have died while trying to kill each other. I buried both of them, because we Chinese believe in people resting in peace," he said. "But deep inside, I really hope that the Japanese will acknowledge the history and all the suffering their war brought to the Chinese and to their own people. Only when that happens will the dead rest peacefully."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 04/22/2015 page6)

Weird stuff you can buy on Taobao

Weird stuff you can buy on Taobao

Top 5 wealthiest women in world's tech sector

Top 5 wealthiest women in world's tech sector

Outsiders challenge traditional smartphone makers

Outsiders challenge traditional smartphone makers

Helicopter replica on the road

Helicopter replica on the road

Chinese real estate deals in US topical forum

Chinese real estate deals in US topical forum

Singing Chinese language's praises

Singing Chinese language's praises

Foreign girls join in ancient Chinese coming-of-age ritual

Foreign girls join in ancient Chinese coming-of-age ritual

Shanghai auto show kicks off

Shanghai auto show kicks off

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Obama submits nuclear energy cooperation deal with China

US urges Japan to handle wartime history in constructive way

Mexico bans poultry, egg imports from bird flu-hit Iowa

Bloomberg: Chinese investment sustains US cities

Bloomberg: Chinese investment sustains US cities

China, Pakistan elevate ties, commit to long-lasting friendship

'Belt-Road' to exchange goodwill with economic coopertation

Swarm of Chinese applications deplete US investor visas

US Weekly

|

|