Beijing looks to cure its medical malaise

Updated: 2015-12-09 07:52

By Wang Xiaodong(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

The capital's top legislative body is mulling proposals to improve its controversial 'dual-number' system for emergency health services, as Wang Xiaodong reports.

Beijing's emergency medical services will be subject to stricter regulation and greater scrutiny if a draft proposal currently being reviewed by the Beijing People's Congress becomes law.

The draft specifies a number of stringent, mandatory standards and procedures to eradicate profiteering, ensure that service providers dispatch ambulances immediately after receiving emergency calls and guarantee that patients are always either taken to the nearest possible hospital, or to a hospital specified by their family.

Operators will also be obliged to make their charges public, according to the draft, which proposes fines of as much as 100,000 yuan ($15,600) for violators.

If the proposal becomes law, service providers will come under the supervision of the Beijing health authorities, while relevant government departments will have the power to guide and manage their activities in cases of emergency or public safety.

The Beijing People's Congress, the capital's top legislative body, said the public's right to basic healthcare is "non-negotiable" and should be guaranteed by service providers under the supervision of the government, rather than through market forces and the profit motive.

End of an era?

The proposed changes could spell the end for the capital's unique, but controversial, "dual-number" medical emergency system, under which two separate operators compete to provide almost identical services.

The system has recently come under fire after one of the providers, the Beijing Red Cross Emergency Rescue Center, was accused of delaying a patient's treatment and providing an inconclusive and potentially life-threatening diagnosis.

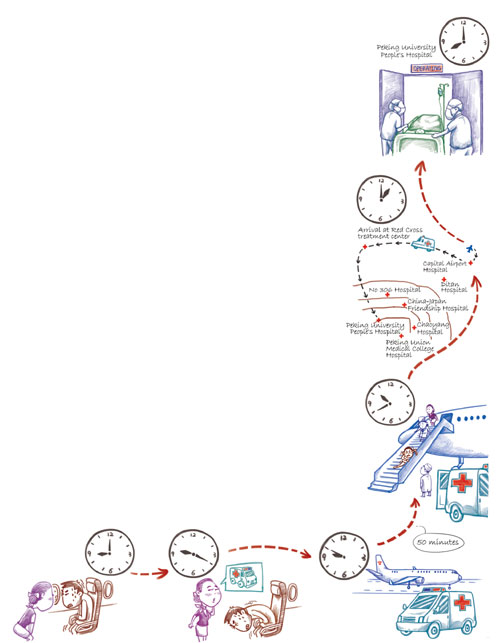

On Nov 9, Zhang Yang, a journalist with the Liaoning Radio and Television Station in Shenyang, Liaoning province, developed an acute intestinal obstruction during a flight from Shenyang to Beijing.

The 35-year-old claims that a Red Cross ambulance transferred him to the organization's treatment center, rather than a better-equipped hospital nearby, and although he spent three hours in excruciating pain at the center, the doctors were unable to determine the cause of his problem.

Zhang claims the center only agreed to take him to the Peking University People's Hospital, one of the capital's leading medical facilities, after the intervention of a physician friend who insisted on the transfer.

By the time Zhang arrived at the hospital, though, his condition had deteriorated to the point where surgery was unavoidable.

The Red Cross center admitted that its ambulance had transferred Zhang to its treatment center against the advice of the medical practitioners at the Beijing Airport Hospital, but insisted that it was the best option, given severe congestion on the capital's major roads and the center's close proximity to the airport.

On Sunday, the center apologized to Zhang in a statement on its micro blog: "We failed to provide more hospital options when transferring the patient, and we did not pay enough care to the patient during treatment."

Unique, but flawed?

Unlike other parts of China where there is only one number for medical emergencies - 120 - Beijing has two main service providers: the Beijing Red Cross, which can be reached by dialing 999, and the Beijing Emergency Medical Center, supervised by the Beijing Municipal Commission of Health and Family Commission, which uses 120.

Ma Yanming, an official at the Beijing Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning, said the organizations share similar functions, but the Beijing Emergency Medical Center doesn't operate treatment centers and only transports patients to hospitals, while the Beijing Red Cross Emergency Rescue Center has its own treatment center.

Although the Beijing Emergency Medical Center provided treatment at its own hospital when it was first established in 1988, the services were withdrawn in 2005.

"The primary reason for stopping 120 (the Beijing Emergency Medical Center) from running its own hospital was to eliminate possible conflicts of interest when it provided emergency services for its own hospital," Ma said.

The reasons behind the founding of the Red Cross center, despite the existence of the Beijing Emergency Medical Center, were essentially market-driven. "The main reason was to introduce competition into the sector and meet market demand," he said.

Yu Ying, a physician who worked in the emergency department at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital for 10 years, defended the Red Cross center, saying the services it provides are essential because a lack of staff and ambulances at the Beijing Emergency Medical Center means it is unable to meet demand in the capital.

Although the Red Cross treatment center was at the center of Zhang's complaint, he was also critical of the carrier, China Southern Airlines, and said he was forced to wait nearly 50 minutes for the plane doors to be opened after landing at the Beijing Capital International Airport, even though an airport ambulance was waiting for him outside.

He also claimed he was forced to "crawl" to the ambulance unaided because members of the cabin crew were quarreling about which of them should transfer him to the ambulance and who should be held responsible in the event of a mishap.

In a statement, China Southern said a malfunction in the plane's braking system had prevented it from taxiing to its allotted parking berth after landing, so the crew had to wait until the aircraft had been towed to the correct location before the doors could be opened.

Beijing Capital International Airport said it would improve coordination with airlines and upgrade its emergency rescue system to ensure that the lives of sick passengers remain the top priority in the future.

The airport ambulance took Zhang to the Beijing Airport Hospital, where the doctors suggested that he should be transferred to either the Beijing Chaoyang Hospital or the Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

An ambulance was requested from the Red Cross center to transfer Zhang to one of the hospitals, but he was instead taken to the Red Cross treatment center, a move driven by the profit motive, according to Zhang, who said the doctors at the center, unable to determine the cause of his problem, even asked him if he had taken illegal drugs.

Zhang Yang's experience exposed mismanagement and a lack of coordination at the airport, according to Zhang Qihuai, a lawyer specializing in aviation at the Beijing Lanpeng Law Firm.

"Airports should give the highest priority to emergency cases involving passengers' lives," he said. "Both airports and airlines should implement effective emergency plans to ensure that patients receive the best possible treatment as quickly as possible."

The Red Cross center became the focus of sustained public criticism after Zhang posted an account of his experience on his micro blog in late November, prompting a raft of comments.

"It's not unusual for 999 and 120 crews to take patients to the hospitals with which they are associated. Some of my friends have had similar unfortunate experiences," wrote one netizen under the username "jasmine0714".

Irregularities

Yu, the former emergency room doctor, said Beijing's emergency services often transport patients to hospitals where they have connections, which means irregularities - such as emergency staff accepting kickbacks from hospitals - are commonplace.

In 2009, the family of a man surnamed Lin who died at the Beijing Red Cross center after a car accident accused the staff of being reluctant to transfer him to a better-equipped hospital. A court in Beijing later ruled that the center should bear half of the responsibility for Lin's death, and ordered it to pay the family compensation of 167,500 yuan.

"To regulate the market, it is imperative that the emergency transfer of patients is completely separate from their treatment at the hospital," Yu said, adding that the problem has been exacerbated by a severe shortage of experienced doctors.

"When I worked at the emergency department at Peking Union Medical College Hospital three years ago, there was a serious outflow of doctors and nurses," she said. "More than 80 percent of the doctors usually quit after working for just two or three years."

The excessive workload and poor pay were the main reasons for the talent drain, she said. "This is a serious problem. How can patients receive good emergency treatment if experienced doctors constantly move on, leaving only inexperienced practitioners to do the job?"

The laws governing emergency services need to be updated and improved to provide badly needed supervision of emergency rescue services, she said. "Greater government investment is required to ensure the sector's healthy development."

Although Zhang Yang said he had accepted the Red Cross center's apology, he stressed that he wants to see the system improve.

"My aim in continuing to fight in recent days was not to gain anything personal, such as an apology or compensation. What I want to see is a change for the better in the current emergency medical rescue system, even if it's just a small improvement. However, I am now confident that it will change for the better."

Contact the writer at wangxiaodong@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily USA 12/09/2015 page6)

- People exit rebel-held area in Syrian peace deal

- Two DPRK music groups to perform in China

- False bomb alert prompts security measures at Mexico City airport

- Russia fires missiles at IS positions

- US House passes bill to tighten visa waiver program

- Obama, Modi vow to secure 'strong' climate change agreement

Panchen Lama enthronement 20th anniversary celebrated

Panchen Lama enthronement 20th anniversary celebrated

Printer changes the chocolates into the 3rd dimension

Printer changes the chocolates into the 3rd dimension

Think all Chinese dama do is dance, buy gold? Think again

Think all Chinese dama do is dance, buy gold? Think again

China's top 10 venture capital firms

China's top 10 venture capital firms

33-car pileup leaves six dead, four injured in Shanxi

33-car pileup leaves six dead, four injured in Shanxi

US marks 74th anniversary of Pearl Harbor attacks

US marks 74th anniversary of Pearl Harbor attacks

Christmas lights across the world's shopping districts

Christmas lights across the world's shopping districts

Top 10 best airports where flight delays aren't a pain

Top 10 best airports where flight delays aren't a pain

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|