Orville Schell looks at what makes today's China tick

Updated: 2013-09-27 11:47

By Michael Barris in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

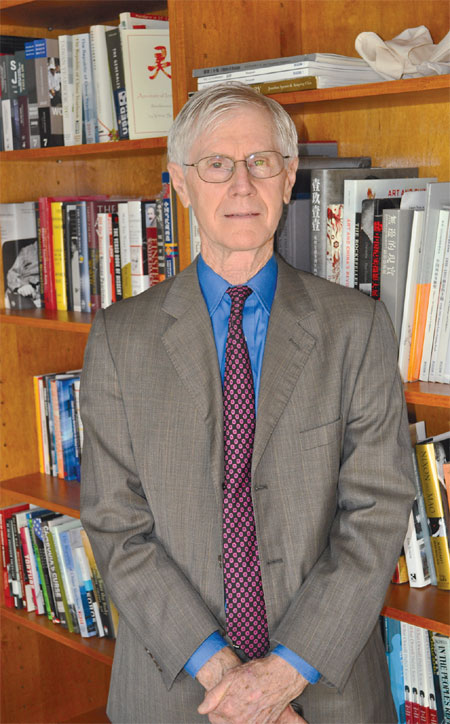

Author Orville Schell, Arthur Ross Director of the Center on US-China Relations at the Asia Society in New York City.Michael Barris / China Daily |

China's modern history is messy, to say the least. As Orville Schell puts it, "It looks like a series of dead ends, failures, unsuccessful reforms, and halted resolutions." Despite 30-plus years as a China scholar and journalist, Schell admits, "I hadn't been able to really make sense out of it."

Until now.

Schell, the director of the Center on US-China Relations at the Asia Society in Manhattan, has co-written Wealth and Power: China's Long March to the Twenty-First Century (Random House, New York). The critically acclaimed book's premise is that China attained its economic prosperity and influence due to its 150-year weaving of a national narrative of foreign exploitation and victimization, starting with its humiliation in 1842 by the British in the First Opium War.

"There is a deep yearning for China to restore itself to a position of greatness," Schell says during an interview in his office at the Asia Society. "And the initial challenge was to become strong enough and rich enough that it wouldn't be bullied."

Schell and his co-author, John Delury, the US-China Relations Center's former associate director, organized the book around the lives of 11 major officials, writers, activists and leaders in China's evolutionary drama, all of whom are captivated by the notion of overcoming national humiliation and securing national wealth and power.

In terms of achieving the latter, China's success has been nothing short of dazzling. Since the introduction of economic reforms in 1978, China has been the world's fastest-growing major economy. Currently the world's second-largest economy, it is on track to overtake the United States as the world's leading economic power by decade's end. Both its military might and its influence on the international stage are growing.

But while it is one thing to be powerful, it is another thing to be respected, Schell says, reiterating the book's conclusion.

With prosperity in hand, China now is entering "another stage which I don't think it quite foresaw," Schell says. "And that is to be a society that people elsewhere in the world admire. This is really what soft power is about. The allure of one society for another, to make people want to go there, be there, become citizens, look at their films, read their books. It's the overt form of admiration."

China's leaders, Schell says, are sometimes "a little incredulous that (China's attainment of wealth and power) shouldn't turn the trick in terms of attaining soft power and global respect. It turns out there's another chapter ahead - another challenge, which is how do you reorganize yourself in a way that makes people feel comfortable, that makes people feel enticed by your social, cultural, political and economic experiment?"

If China wishes to be "a truly great power - a power that is respected and possibly even admired by other countries and societies," Schell says, "it does need to work out a proper balance between the government and its people."

Power act

Very often, he says, "the United States has not been a very good example" of striking an effective government-public equilibrium: "Look at the pre-Civil Rights movement. Look at the Vietnam War, the Iraq war, the treatment of people who disagreed with those policies. The United States did not act like a great power, certainly not like a great society. So I think China too, has its issues."

That tone of activism that runs through Schell's speech reflects his pedigree. His father, Orville Schell, Jr, was a prominent lawyer - "a conventional straight-laced corporate lawyer who had a conscience," Schell says. Besides heading the New York City Bar Association, the elder Schell chaired the Human Rights group Americas Watch and cofounded Helsinki Watch, forerunner to Human Rights Watch.

How did his father's viewpoint influence Schell? "You certainly were aware - he had a very international view of things," Schell, 73, recalls. "He was a deep believer in justice for all. I do believe there are certain human values which people in all countries share and have some obligation to protect for each other." Schell would eventually come into his own as an activist, when as a writer involved in anti-war activism and journalism, he joined others who refused to pay tax as a protest against the Vietnam War.

Born in New York, Schell began earning a bachelor's degree in Chinese studies, jumping from Stanford University to National Taiwan University. Transferring to Harvard University, he added Asian history, culture and politics to the mix. While pursuing a master's degree in Chinese studies at the University of California, Berkeley, he teamed up with a professor to co-author a three-volume work, The China Reader, that would be the first of his numerous books and articles on China.

Writing widely for magazines such as The New Yorker, Harper's, and The Nation, and coproducing China-related programs for the Public Broadcasting Service and CBS' 60 Minutes, led to Schell's selection as dean of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Today, as the Arthur Ross Director of the Center on US-China Relations at the nonprofit Asia Society, he oversees a program of multimedia journalism, research and public events aimed at forging closer ties between Asia and the West.

Permanent revolution

He first visited China in 1974, during the last years of Mao Zedong's era. Schell acknowledges being awed at Mao's Marxist pursuit of "permanent revolution" which aimed to reverse the dominance of Confucian passivity and purge China of its ancient notions of order in an effort to unleash the country's productive forces.

Schell says Mao's actions can be seen as clearing the way for Deng Xiaoping, starting in 1978, to advance market-oriented reforms that would ultimately lead to China's economic explosion, improved standard of living and a new brand of socialist thinking. "You may not like Mao, you may not think he was a kind man, but looked at through the eyes of history, you have to say that China through his revolution broke loose from its past," Schell says. "When Deng Xiaoping came along, there wasn't a lot of cultural resistance. Women had been freed. Families were not so conservative."

Schell calls co-writing Wealth and Power "one of the most wonderful experiences of my intellectual life". Although other authors have grappled with China's rise to prosperity, "we wanted to make our book very essayistic, wanted to make it a personal historical discovery, not just research", Schell says. "To help Americans and Westerners come to some conclusions about - how did China get here? Nobody has answered that question. Westerners would struggle for decades to figure out various theories of development. How does a country that was poor and backward - how does it develop? And none of those theories had any relevance to the Chinese experience."

michaelbarris@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 09/27/2013 page11)

Serena Williams back to Beijing for new crown

Serena Williams back to Beijing for new crown

'Battle of the sexes' to start China Open

'Battle of the sexes' to start China Open

US astronaut praises China's space program

US astronaut praises China's space program

Christie's holds inaugural auction

Christie's holds inaugural auction

Aviation gains from exchanges

Aviation gains from exchanges

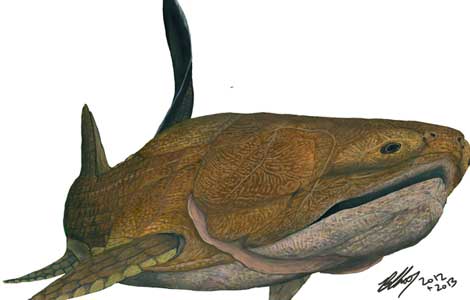

Early fish ancestor found

Early fish ancestor found

Singers' son sentenced to 10 years for rape

Singers' son sentenced to 10 years for rape

Djokovic announces engagement to girlfriend

Djokovic announces engagement to girlfriend

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US arms sales to Taiwan still sticking point

Can the 'Asian pivot' be saved?

Trending news across China

Overseas entrepreneurs connect with reform

Russia to guard Syria chemical weapon destruction

Interpol issues arrest notice for 'white widow'

US astronaut praises China's space program

Wang, Kerry meet second time

US Weekly

|

|