Can Mandarin go from strength to strength?

Updated: 2015-11-21 00:40

By Riazat Butt(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

|

US high school students who participate in a summer camp learn calligraphy in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province in China . provided to china daily |

Ambitious push to introduce more Chinese-language programs in schools comes amid staffing issues and funding cuts, Riazat Butt reports.

Nick Marro spent five years learning Mandarin in the United States before he went to China. He had a two-month stint in Shanghai in 2010 and then spent all of 2012 at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for American-Chinese Studies.

“Being in China was like a water cannon to the face,” recalled the 25-year-old from Fairfax County, Virginia. “The Chinese I spoke with my classmates was not the Chinese I’d used in my textbooks.”

He overcame that shock and went on to find a job conducting research on Chinese commercial policy for a trade association in Beijing. “I always knew I’d do something in China, or with China. I think that much of China is the future, whether it’s business or cultural exchange. China is going to be at the epicenter.”

The White House is of a similar opinion.

Secretary of State John Kerry has described the US-China relationship as “the most consequential in the world”, while President Barack Obama used President Xi Jinping’s inaugural visit to announce a dramatic expansion of a 2009 initiative aimed at improving student engagement with China.

At a joint media conference with Xi on Sept 25, Obama set a target to have a million American students learning Mandarin by 2020. “After all,” he said, “if our countries are going to do more together around the world, then speaking each other’s language, truly understanding each other, is a good place to start.”

Carola McGiffert, president of the 100,000 Strong Foundation, an independent nonprofit organization, is responsible for getting 800,000 more K-12 students learning Chinese and meeting the new target.

“There are two different 100,000 goals,” she explained. “One is to have 100,000 young Americans studying abroad in China. The president announced we’d reached that number (and) wanted to set a new ambitious goal and grow the next generation of leaders.”

Her foundation has three main areas of focus. The first is to deliver a Mandarin-language curriculum that each state can adopt and tailor to its needs, she said. “The second thing to address is the lack of teachers. The Chinese government provides guest teachers, and we’re extremely grateful, but it’s not a scale model. They are here for two or three years, and they don’t have extensive experience of the American school system. We need to grow our domestic teaching corps as well as teaching colleges.”

According to a Asia Society report in 2010, if studying Chinese becomes as common as German (280,000 learners), the US would need 2,800 teachers over the next five years, and if it became as common as French (roughly 1 million learners), the US would need 10,000 teachers.

McGiffert estimated that there are only a few thousand Mandarin teachers in the US, including several hundred sent by Beijing.

“Our third area of focus is technology,” she said. “People need to leverage the technology that exists out there to access communities.”

The 100,000 Strong program is for students from all socio-economic backgrounds, but she admits that the current program is still not accessible enough.

“We have a very diverse country, and we need to make sure people from all backgrounds have access to Chinese language and culture,” she said. “Language is important. Chinese is a lens into the culture, but there is no replacement for being in the country and interacting with people. The study-abroad experience is incredibly valuable.”

She added that the foundation plans to launch a $25 million funding drive in the coming months to help meet Obama’s new target.

But there is more to the initiative than improving the linguistic capabilities of teenagers, according to McGiffert. In an article for The Hill in October, she wrote that the US-China strategic relationship was at a critical juncture: “While the bilateral relationship may, for the foreseeable future, be characterized by contention and competition, we must not let it drift toward conflict. We all — from the administration to members of Congress to the American people — must proactively seek opportunities for collaboration.”

The push for more Mandarin education comes at a time when the US government is cutting foreign language funding. In 2012, the Senate passed a bill eliminating the $27 million Foreign Language Assistance Program, the only federally funded program supporting foreign language instruction in K-12 schools, immersion programs, curriculum development, professional development and distance learning. A note on the Department for Education website said the cut affected existing grant-holders and future bids for funding.

In 2011, before the cut was finalized, Marty Abbott at the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages told the Huffington Post that higher education spending for foreign languages had already been cut by $50 million, down 40 percent on the previous year.

In June, the Senate Appropriations Committee also proposed a $35 million (25 percent) reduction to the Department of Education’s Title VI and Fulbright-Hays programs, which provide specialist language and area training for academics, aid workers and diplomats.

“It comes down to national capacity,” Dan Davidson, president at the American Councils for International Education, told China Daily. “Who is going to teach these people and how ready are they? Are the schools ready to respond to this challenge? There are federal initiatives to support the interaction with Chinese culture or encourage students to study abroad in China.”

He said his organization had surveyed 29 states and discovered there had been “a remarkable jump” in enrollment in Chinese study programs at K-12. According to its research, in California, enrollment rose 66.5 percent between 2007 and 2014-15, from 12,710 to 21,157, while in Ohio it went from 2,292 to 10,971, an increase of 378 percent. In Maryland, it rose from 3,000 to 7,770, and in Wisconsin, from just 472 to 4,970.

“This is full-time mainstream education. If you were to add on evening or weekend classes and private tuition, it would be considerably more,” he said, adding that the councils’ last census showed there were 125,000 students in all. “And we’re well on the way to beating that.”

But it is not enough for students to learn Mandarin; they have to stick with it, he said.

Marro said he had specific reasons for wanting to learn Chinese: “I’m half Asian — my mom is Malay — and we have Chinese cousins. I had a huge identity crisis — about whether I was white or Asian, and part of the way to deal with that was to explore my heritage.”

His high school did not offer a Chinese study program, but he was aware of one that did and got the help he needed to pursue his interest. Later, he enrolled in a four-year degree in Chinese language and literature at the University of Virginia.

Not every high school or university will have the resources to accommodate students wanting to learn Chinese, he said, but there needs to be funding for language departments to survive.

Marro welcomed the drive to get more high school students learning Chinese, but he foresees problems: “Not everyone is going to be super passionate about Chinese like me. Having been a high school student and having seen the environment, it’s going to be a challenge, and starting early is important.”

He emphasized the need to spend time in China, to get the “water cannon” effect. “Spending time in the target country is crucial. When I left college I graduated with 20 people who either had a major or minor in Chinese. I was one of three people who made it out here.”

The fact American students can gain from studying in China is not in dispute, according to Professor Joseph Stetar, an education policy expert at Seton Hall University, New Jersey. In a piece for University World News last year, he asked how the benefits of 100,000 Strong could be maximized and quoted a 2013 report from the Institute of International Education that said 26,686 US students studied in China in 2011. However, he explained, more than 20,000 were engaged in short-term, study-abroad credit programs or study tours where the opportunities for integration into a Chinese university were limited.

“Only 2,184, less than 10 percent, were enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degrees in Chinese universities, and many of those were in programs where English, not Chinese, was the medium of instruction.”

He quoted 2014 data from the international office of Peking University, one of China’s elite higher education institutions, that showed 56 of the 1,619 international students enrolled in the college’s undergraduate degree programs taught in Chinese were American. For its graduate degree programs, the number was 37 of the 630.

With China’s elite universities being “fertile breeding grounds” for future leaders, it would be hard to characterize an effort that resulted in only 93 American students enrolled in Chinese-medium degree programs at Peking University as being successful, Stetar wrote.

“More needs to be done to prepare and support American students who can score sufficiently on the HSK (the standardize Chinese-language test), to gain admission and succeed in Chinese-medium degree programs,” he added.

- London tube station evacuated over security threat

- China law firm Yingke opens China Center in London

- ROK accepts DPRK's proposal for working-level talks

- DPRK proposes working-level talks with S. Korea

- France, Russia launch more strikes against IS targets in Syria

- Chinese bearing maker prepares Michigan facility

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

Snow hits North China as temperature drops

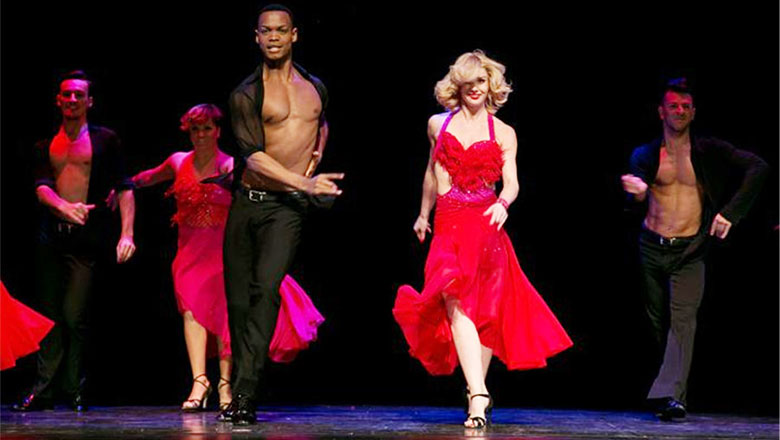

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

'Burn the Floor' thrills its Beijing audience

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Where do China's damaged currency notes go?

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Shenyang's 50 gas-electric hybrid buses to hit the road

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Top 10 global innovators in 2015

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Leaders attend APEC welcome dinner in Manila

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Amazing finds unearthed at the Marquis of Haihun's tomb

Automakers debut key models at LA Auto Show

Automakers debut key models at LA Auto Show

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

Xi pledges $2 billion to help developing countries

Young people from US look forward to Xi's state visit: Survey

US Weekly

|

|