Sculptural flights of fancy

Updated: 2013-04-26 07:23

By Mike Peters (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Joel Shapiro's Now, a work that was more than six years in the making, in Guangzhou. Provided to China Daily |

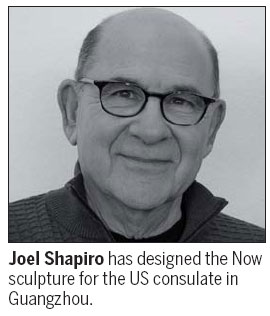

Joel Shapiro's huge aluminum sculpture in Guangzhou draws many interpretations

When Joel Shapiro went to work designing a massive sculpture for the new US consulate in Guangzhou, he didn't conceive it as "birdlike". That's the recurring adjective when people describe the finished piece, Now, and Shapiro doesn't mind a bit.

"I can see that," he says on his return to New York after supervising installation of the huge blue piece in China. "It's perfectly OK.

"What I wanted to project was a sense of uplift, make it celebratory and a reflection of individual spirit. It's a projection of thought into form: I don't know that there is any greater, deeper meaning."

There are all kinds of references that people can see, he says, though he avoided any suggestion of the number 4, which he learned is unlucky in Chinese tradition.

"I think there's a broad way for people to interpret work, and I'm totally up for an interpretation though I don't always agree with it based on their own experience." An art academic might view his work in the context of the history of sculpture, he says, while casual observers might be reminded of animals they liked.

The fact that there is no overriding narrative, "that's easier if you are doing work that is more explicit", is typical of his work. Now is composed of six pieces of painted aluminum that come together in a radical configuration but barely touch each other, another hallmark of a Shapiro piece.

At almost 7 meters tall, the piece was "a bit" too big for Shapiro to cut and put together in his studio.

"People suggested building it in China," he says, "and I'm sure it could have been done it would have been fun to do, in fact. But I would have had to be there, and I just didn't have the time."

So Shapiro teamed up with KC Fabrications, in Gardiner, NY, just south of New Paltz, and the fabrication took about nine months. After that, he toyed with the idea of hand-painting it himself.

Though he was tempted, he was not sure he could get the necessary adhesion, so he took advantage of new spray-paint technologies that have made it easier to get the look he wanted - paint the Pentagon has developed for military vehicles.

That included a matte finish.

"In the past, the only good paints were shiny," he says. "With matte you read the form, shiny you read the surface. You don't want the shiny, glossy, Buick look."

Since his first exhibition in 1970, Shapiro's work has been the subject of many one-person shows and retrospectives in the US and Europe. Prominent commissions include the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington; Conjunction, commissioned by the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies for the US embassy in Ottawa, Canada; and a public commission, Verge, for 23 Savile Row, London.

On April 30, FAPE which commissioned the Guangzhou piece will celebrate the work of Shapiro and others at a reception and dinner, where Shapiro will ceremonially present Now's design to US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Shapiro was not fazed when asked to create a "site-specific" work for Guangzhou - a place he had never seen.

"When the commission was initiated, the site was not developed. I had a full set of plans, and I built models of the site and the piece." Shapiro studied what the city looked like, and consulted frequently with building's architect, Craig Hartman of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, to integrate the work within the overall design. "I saw models of the building at the SOM offices in San Francisco," he adds, "so I felt quite comfortable with what I was doing."

That was true even when the consulate building expanded literally on the drawing board, becoming two stories instead of one.

"Adding one floor didn't really affect the scale of my piece. It's still big, expansive and functions well, one of the best sculptures I've made."

Six years after the process began, Shapiro and the six pieces of his sculpture were ready to head for China.

"It was carefully packed, and the fellows who built it went over and spent a week installing it. We had a great crane operator in Guangzhou who couldn't speak a word of English, but apparently hand signals are all the same everywhere," he says, making a circling motion with his hand that everybody understood meant "go slowly".

Shapiro says he was thrilled with the result.

"What did surprise me was the amount of light there was at night, and the pale but very intense blue paint color shows up very well in the evening landscape."

"The piece is really about my interest in form. I didn't want it to offend, but I wanted it to enliven the dialogue of form in the city.

"Guangzhou is a growing and changing city and it is a great honor to be asked to make a sculpture in such a vibrant context," he says.

That context includes Zaha Hadid's internationally acclaimed Guangzhou Opera House, which sits on the Pearl River across the street from the new consulate site. The juxtaposition prompted a last-minute adjustment in the installation plans, Shapiro says.

"In my original concept, my sculpture was situated so that it pointed at the opera house. It was an acknowledgment, pointing it out. But in Chinese culture pointing at something can be considered impolite, so we turned the piece to face another direction."

Because the consulate building will not be ready to open until later this year, there was no public event during the Now's installation, which disappointed Shapiro. But he got other opportunities to interact with locals, especially art students.

"I gave a couple of talks, one at Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and another at the Times Museum. The academy is divided into three sections: representational, abstract and public works, though even the kids in the abstract discipline were doing some representational stuff, with more references beyond the actual work.

"The students at the academy were advanced, very bright. They could have been students anywhere. Clearly sculpture plays a role in Chinese culture. You could tell when you showed images in a lecture I tried to show work that traced my own development. Sculpture has a universal language - a common alphabet - though it's affected by your own reference.

"I think they understood perfectly what I was doing."

michaelpeters@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 04/26/2013 page20)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

No let up in home price rises

Bird-watchers undaunted by H7N9 virus

Onset of flood season adds to quake zone risks

Vice-president Li meets US diplomat

China has a tourism law

Meeting delivers big deals

China denies border spat with India

Chinese consumers push US exports higher

US Weekly

|

|