View

Yuan blame game a distraction

By Dan Steinbock (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-19 07:56

|

Large Medium Small |

As the November mid-term elections in the United States approach, the Democrats and the Republicans have both found a new villain to run against. "China emerges as a scapegoat in campaign ads," as The New York Times recently put it.

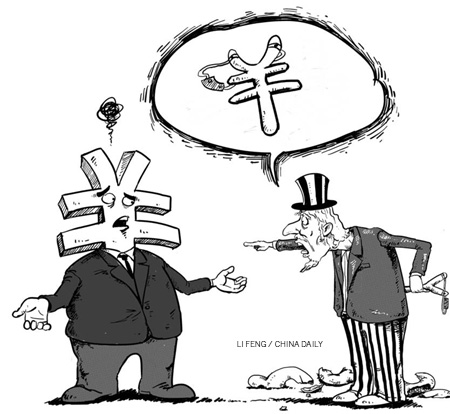

The China blame game is taking place amid escalating trade tensions. As the US puts pressure on China to allow its currency to increase in value, the rising euro and yen have led the European Union (EU) and Japan to join the chorus. The charges are not new, but the tone has escalated steadily since early summer, when the prospects of the Democrats' loss in the mid-term elections became evident.

Due to economic stagnation, political polarization and unemployment in the advanced world, the yuan has become a convenient scapegoat. Yet the very concept of "currency manipulation" is flawed. Today, all governments take measures that affect the exchange rates directly or indirectly.

The debate over "currency manipulation" moved to a new level in September, when the US House of Representatives approved legislation that would allow the US to seek trade sanctions against China and other countries for "engaging in currency manipulation" to gain trade advantages.

However, cheap imports from China have not been the primary cause for the decline of manufacturing output or job losses in the US. Even a significant exchange adjustment would not bring the lost low-cost jobs back to the US. Instead of importing low-cost products from East Asia, US consumers would just buy them from Vietnam, Bangladesh or Sri Lanka.

Had China been the primary cause for the US trade deficit, China would have accounted for it. In reality, when the US trade deficit peaked in 2007-08, China contributed a third of the deficit, while Japan, Russia and oil-producing countries accounted for the rest.

Last year, China's current account surplus was 6.1 percent of GDP, whereas Saudi Arabia's amounted to 11.5 percent. In Germany and Japan, the comparable figures were 6.6 percent and 5 percent. Yet neither Saudi Arabia nor Germany nor Japan has been accused of currency manipulation.

Right before the euro crisis in spring, the US enjoyed the benefits of the strong euro. By the logic of "currency manipulation", the EU should have accused the US of manipulating the exchange rate to boost exports at the expense of the euro zone.

When George W. Bush was the US president, the White House supported free trade but stood for unilateralism in security. In contrast, the Barack Obama administration has supported multilateral security policies but has been flirting with unilateralism in trade. Consequently, a series of currency frictions have been sparked worldwide because global rebalancing has failed.

By the logic of the US House of Representatives, Washington should challenge dozens of nations worldwide for currency manipulation - including itself. After all, every country has the option to or not to devalue its currency. In the advanced world, the preferred option has been "quantitative easing" (QE). In 2008, the US Federal Reserve resorted to QE to overcome recession by printing more currency notes and injecting it into the national economy.

Other G7 nations followed in the footprints. Fed chief Ben Bernanke has made a case for a second round of QE in the US, which will be accompanied by more of the same in the United Kingdom, and Japan.

Since QE, essentially, devalues a country's currency, it is also a form of "currency manipulation". It is not direct but an indirect currency intervention. Yet the net effect is the same.

QE encourages speculators to bet that the currency will decline in value. The large increase in the domestic money supply will lower domestic interest rates, which prepares the conditions for a carry trade (investors borrow low-yield currencies and invest in high-yield ones).

China and other emerging economies could thus use the logic of the House of Representatives to accuse the US and other G7 nations of "currency manipulation" that may deepen stagnation. As a result of QE, "hot money" is driven into the high-yield emerging economies, which is likely to further inflate dangerous asset bubbles in emerging Asia.

New rounds of QE may not do much to stimulate the economy, but they have the potential to disrupt global recovery. US critics argue that a new QE is more likely to debase the dollar and thus accelerate "debt monetization", inflating away the soaring US debt.

In October 2008, the joint threat of global financial meltdown and converging national interests prompted the G20 to form a common front. Today, different regions are recovering at different speeds. As a result, national interests have diverged and cooperation is more difficult.

In the US, Western Europe and Japan, China has been portrayed as the problem. This conveniently diverts public opinion from the deteriorating dollar.

Undue pressure on China is the wrong approach to the problem. China's current account surplus has declined, its domestic demand has increased dramatically; and its real exchange rate has appreciated by more than that of any other large country in comparison to the 10-year pre-crisis average.

Effective global rebalancing requires international and multilateral cooperation. The currency blame game has the potential to undo much of the post-crisis gains in the world economy. It is just another distraction from the painful long-term structural reforms that are vital for the global recovery.

The author is the research director of International Business at the India, China and America Institute, an independent think tank in the US.