Focus

Animal live show ban nears

By Hu Yongqi and Zhang Leilong in Zhengzhou, and Duan Yan in Beijing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-23 08:04

|

Large Medium Small |

|

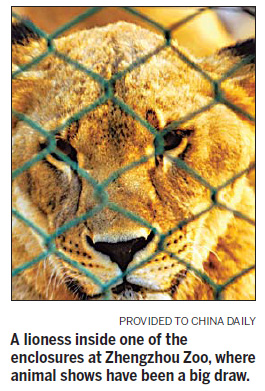

A lion performs a balancing act on a rolling ball during a performance at Zhengzhou Zoo in early November. Xiang Mingchao / China Daily |

Zoos cagey as many will struggle to survive after January deadline. Hu Yongqi and Zhang Leilong in Zhengzhou, and Duan Yan in Beijing report.

As the black bears rode around the ring on bicycles, Xiang Xiaohui clapped her hands and screamed, her face a picture of excitement.

"It's amazing," said the thrilled 9-year-old, as she sat with 500 others watching the show at Zhengzhou Zoo, the largest in Henan province. "The lions also ride horses here instead of eating them, like it says they should do in my school textbooks."

For many youngsters like Xiang that afternoon, it was the first time they had seen such daring stunts. It is also likely to be the last.

As of January, all 250 or so public zoos and wildlife parks nationwide will be banned from staging live shows as part of fresh efforts by the central government to improve animal welfare.

The move strikes a blow for animal rights groups in their battle to improve the treatment of wildlife in China.

Yet, it will also have a serious economic and cultural impact.

Zoos will lose a lucrative revenue stream and animal trainers argue the blanket ban will take away their livelihoods.

Unlike in some countries where wildlife parks are heavily subsidized by the government, zoos in China rely on their incomes to cover daily running costs and are largely profit-driven businesses.

Zhengzhou Zoo, for example, only receives money from the municipal authorities for projects involving rare species or necessary repairs. Everything else is paid for with the revenue it makes on entrance fees.

Experts say the need to make a profit is largely to blame for the rampant exploitation of animals.

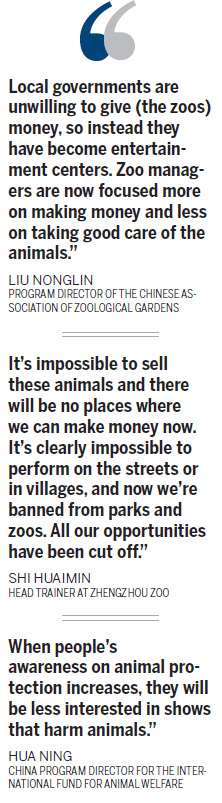

"Local governments are unwilling to give (the zoos) money, so instead they have become entertainment centers," said Liu Nonglin, program director of the Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens. He worked with officials from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development to draft the new regulations.

"Zoo managers are now focused more on making money and less on taking good care of the animals," said Liu.

According to figures provided by its management office, Zhengzhou Zoo receives more than 1 million visitors a year and generates roughly 20 million yuan ($3 million). Almost half of that money, however, comes from ticket sales for its animal shows.

With the combined salaries of its 146 employees topping 3.6 million yuan, cutting the performances will leave a large hole in the budget.

Despite having an adverse effect on the income, Wang Jiantang, the zoo's Party chief, said the new rules will be "resolutely implement".

"After all, it's all for the good of the animals," he added.

End of training

After enjoying the bears' performance, Xiang Xiaohui and her parents were shocked when China Daily reporters told them about the forthcoming ban. They were not the only ones.

In Puyang, Henan's so-called "city of animal training", many people are also struggling to understand why their profession is being outlawed.

"Why is the regulation so one-size-fits-all?" asked Shi Huaimin, 46, a native of the city who heads the team of trainers at Zhengzhou Zoo. "Taming animals is a cultural phenomenon that has existed in Puyang for six, seven decades.

"If we can't perform, there may be no way to protect this heritage and it could disappear entirely," he warned.

The city, which sits on the northern shore of the Yellow River, has been famous for its animal trainers since the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). As residents were unable to grow much on its sandy, barren lands, large numbers were forced to make a living as entertainers, traveling China with monkeys, camels and even dogs. Today, it is a pillar industry that involves more than 400 villagers.

Liu at the Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens said that, although the ban will be tough on communities in Puyang, it is in keeping with "the global consensus that animal performances shouldn't be allowed".

Shi and his team started running the shows at Zhengzhou Zoo in September 2009 after moving from Wuhan, capital of Hubei province.

Performances were originally twice a day, seven days a week, but as the troupe's popularity grew, the number was increased to four a day.

In August this year, an inspection team from the State Forestry Administration ordered the park to cancel two shows - one in which tigers jump through flaming rings, the other involving bears playing with fire sticks - as they feared they "may be harmful to the animals".

The team cancelled the shows but Shi denied any of his animals are mistreated.

"If my son is sick, my wife can take him to the hospital. But if one of the animals gets sick, I immediately come back because these animals are what we live on," he said, his eyes filling with tears.

However, as it is the trainers and not zoos that usually own the performance animals, that bonus could soon become a burden.

"It's impossible to sell these animals and there will be no places where we can make money now," said Shi, who explained that food for 10 animals can cost roughly 900 yuan a day. "How are we going to make this money?

"It's clearly impossible to perform on the streets or in villages, and now we're banned from parks and zoos. All our opportunities have been cut off," he added.

Natural lessons

Although happy about the ban, animal rights campaigners are now urging authorities to further crackdown on wildlife performances through education.

"When people's awareness on animal protection increases, they will be less interested in shows that harm animals," said HuaNing, China program director for the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

Xiamen AnimalProtection Association is also compiling China's first textbook on animal protection, which will be distributed among elementary and middle schools throughout the city on the coast of Fujian province.

After visiting Dalian Zoo in Northeast China's Liaoning province, Xiao Bing, the Xiamen group's chairman, said he was ignored when he complained about employees selling live chickens for visitors to feed the tigers, a practice that is already prohibited.

"The food for these animals is not enough and that's why we have seen more incidents of zoo animals attacking people in recent years. Keeping the beasts hungry will only make them more likely to attack," said Xiao.

China still does not have any laws on animal welfare. A draft of the Animal Protection Law was released in September 2009 but is still under consideration.

The Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens' 10-year development guide for zoos is also still in the design stage.

In the meantime, program director Liu said the new regulations will be the "first step" in guiding the country's zoos back to their original purpose: teaching people about the wonders of nature.

"We have to stop these bad things (like live shows) first and then we'll be free to do more things," he said. "Otherwise, all we'll be doing is putting out fires."

Xiang Mingchao contributed to this story.

|

Dogs perform tricks at Zhengzhou Zoo in Henan province. Animal performances have for a long time been popular in Chinese zoos, which need good ticket sales to boost their revenues. Provided to China Daily |

|

A black bear rides a bicycle as part of a show at Zhengzhou Zoo. The shows will be banned from January. Xiang Mingchao / China Daily |