|

Large Medium Small |

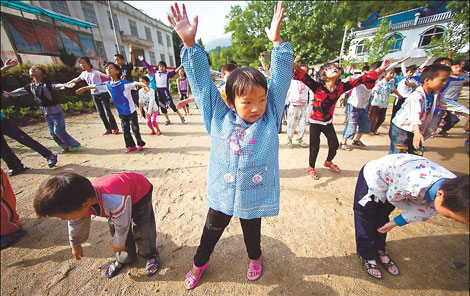

Yangshan Village Primary School students performing their morning exercises on the school's dirt basketball court during a rare break in the rain, earlier this month. Roots & Shoots's Anhui Poverty Elevation Program teaches rural children while building infrastructure. Photos By Jonah M. Kessel / China Daily

|

Roots & Shoots believes education is key to reversing poverty, but sampling rural life is also enlightening for its volunteers, Erik Nilsson finds

It was Australian volunteer teacher Jiang Chao who taught 13-year-old Wu Shengqiao her favorite English-language phrase - "Never give up". But 18-year-old Jiang says that it was Wu and her classmates, who are growing up in one of the country's poorest villages, that taught him what that really means.

Jiang says teaching in Anhui province's rural Yangshan has shown him the power of perseverance when facing adversity.

"I've learned that life's a challenge but you can pull through if you persist," he says. "The kids here are poor, but some of tvhem have amazing English."

Jiang says this realization became even clearer when he met an elderly rice mill operator who lives near the school.

"He has a lot of kids and animals to feed, and machines to pay for, and he's old. But he keeps going and doesn't even think about retirement."

What hardship - and overcoming it - means is one of the lessons NGOs Roots & Shoots and American Field Service (AFS) hope their 30 Chinese and foreign volunteers, aged 16 to 34, get from their experiences.

The volunteers teach summer classes for 50 of the 140 primary school students in Yangshan, a subsistence farming settlement where the average annual per capita income is 1,200 yuan ($177) - and that is a sharp increase from just 700 yuan three years ago.

Yangshan Village Primary School principal Qi Jiaquan says the paving of the village road in 2005, the tourism development of nearby Tiantingzhai National Park and expanding tea cultivation have elevated local incomes. In addition, mobile phone reception became available last year, although there's still no Internet.

But despite improvements, local earnings still hover around a fifth of the national average.

Consequently, one-third of Yangshan's 3,000 inhabitants - almost everyone of working age - have left to labor in cities, mostly in Shanghai and Jiangsu province.

Yangshan's poverty, Qi explains, has mostly been caused by what villagers call "The Three 100,000s".

First, 100,000 locals died in the Civil War. Then, a nearby hydropower project inundated 100,000 mu (6,666 hectares) of land and displaced 100,000 people, he says.

The shortage of taxable incomes has generated little revenue for the local education bureau, which began fully subsidizing students' 300-yuan annual tuition last year.

Qi explains that some parents, who could afford the fees before nine-year education became compulsory, didn't value schooling enough to send their children to school.

"Sometimes, daughters farm while sons go to class," Qi says.

Believing that education is integral to reversing intergenerational poverty, Roots & Shoots entered into a partnership with the school in 2005, the NGO's Shanghai general affairs director Li Yujing says.

The organization first replaced two structurally hazardous school buildings, with the local government matching its 100,000-yuan donation. It then installed a water purification system to treat the water piped from the village's only source.

Because malnutrition has been a longstanding local problem, Roots & Shoots also started providing every student with an egg and milk box on school days. Most villagers' clothing was donated by the NGO, and the organization has run dozens of other projects, from decorating the activity room to planting an organic garden to teach the kids about safer food production.

This year's biggest undertaking was funding construction of a new restroom. The public lavatory students had been using is a rudimentary brick-and-concrete structure without running water.

"Many volunteers tried to go without eating or drinking to avoid using the toilet in the first few days. But they soon learned they couldn't do it," Li says.

Volunteers are forbidden from relieving themselves outdoors and are encouraged to report those who do.

Experiencing rural ruggedness is enlightening for the young urbanites, Li explains.

Volunteers sleep on crowded concrete classroom floors and are allowed to take five-minute showers in pairs every two days. They lashed together the bamboo and tarp shower in the schoolyard on the first of their five days in the village. And they have to chop wood to heat water for showers and cooking meals, which they prepare in shifts.

"Many of them have never washed their own clothes or dishes, but they have to here," Li says.

Jiang says he has learned a lot from the experiences.

"This is an opportunity for me to do stuff I've never done - washing dishes, cleaning rooms and making food."

A housekeeper takes care of chores in his family's home in Shanghai, he says.

German Lennart Zimpfer says he had never before experienced this way of life.

The 19-year-old massages his palms, made sore by a day of woodcutting. "It was really difficult. My hands hurt," he says.

"I wanted to see what it was like to live simply. Shanghai's living standard is the same as Germany's, and it's good for me to see the other side of China."

Volunteers also learn how to make more out of less and why they should, Li explains.

They bring their own chopsticks and receive limited meat rations. They aren't allowed to waste anything.

"Only having five minutes to shower made me realize the importance of water," Shanghai Finance University student Zhang Shiqi says.

But volunteers agree that the children make enduring the rustic conditions worthwhile.

Zhang explains the students and volunteers, many of whom are only children like him, become like family.

"Both (groups) get the siblings they need but don't have," the 19-year-old says. "I wish I could take them back to Shanghai with me."

The children are so eager to attend the program that they often arrive around 6 am, more than two hours before classes. Reaching the school requires hiking up to an hour and a half over mountain trails that melt into slop during the frequent downpours, AFS international cultural program manager Cao Yikai says.

But before the sun has fully unwrapped the morning mists from the mountains, the schoolyard is teeming with giggling kids, poking, tickling and jumping on volunteers.

"This," Cao says, as a boy leaps on his back, "is their favorite activity."

The children's families share their enthusiasm.

Huang Congying says her 5-year-old granddaughter Zhang Yang adores the summer school.

The 62-year-old is raising the girl, while her father does construction work in Zhejiang province and her mother serves as a low-level local official in Hubei province.

"We really welcome Roots & Shoots and hope more programs can run here," Huang says in the local dialect.

While interactions between volunteers and villagers are overwhelmingly warm, clashes do occur, Li says.

She explains villagers rarely shower, wash their hands or brush their teeth.

"Some volunteers can't accept that. They're very surprised when I ask them to not shower for a few days," Li says.

The NGO distributes toothbrushes, teaches the kids how to use them and encourages them to educate their families about hygiene, she says.

Differing ideas about cleanliness also extend to food. Because locals don't have refrigerators, they salt and hang the one or two pieces meat they eat every year. The hunks grow coats of mold that villagers believe add flavor.

And they are eager to share the delicacy - usually reserved for Spring Festival - with the volunteers.

"We're happy they want to give us their best," Li says. "But we feel it's dirty and unhealthy."

Ultimately, the volunteers are thankful the villagers appreciate their contributions. And, as Qi explains, their work is showing results.

Yangshan's students score highest out of the 14 schools in Tiantingzhai town and eight neighboring villages on the local government's third-grade exam, he says.

But the remaining challenges are vast. Courses are overcrowded, and students of different ages and academic abilities must take classes together.

While roughly a dozen students finish the primary school every year, only about 30 have attended university since the school opened in 1982, Qi says.

Yangshan's five primary school teachers lack university educations, but other instructors are unwilling to work in such poor conditions for the 1,500-yuan monthly salaries. The principal says he's worried about replacing a teacher up for retirement.

He places hope in Anhui Normal University student Liu Bangde, one of the few locals to receive higher education.

"I want to become a teacher and return to help kids from my hometown," says the 20-year-old, whose 12-year-old brother studies in Yangshan.

"Liu's story is very meaningful," Li says. "It shows you can come from here and still get a good education."

But the need for quality schooling isn't the sole realm of the university-bound, Qi says.

"Education is important, no matter what work you do," he says. "Yangshan has experienced big changes in recent years. I hope that we could someday be as good as city schools."