|

Large Medium Small |

|

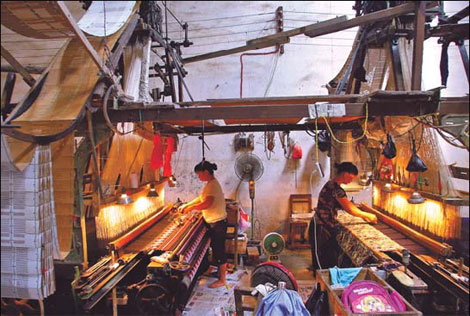

A weaver operates a "primitive" loom nicknamed "the pig basket". Photos by Huo Yan / China Daily |

Hand-woven brocade at the Shanghai Expo sheds light on the beauty of a centuries-old craft that crystallizes the dreams and hard work of the ethnic Zhuang in Guangxi, China's largest ethnic group, reports Raymond Zhou

Yesterday, amidst the fanfare of the opening of Guangxi Week at the 2010 World Expo, a hand-woven tapestry became the centerpiece that wowed the audiences who flocked to Shanghai. Had it been done by weaving machines and stitched together, it would have been nothing extraordinary.

But what seemed like an ordinary piece of handicraft was actually the largest of its kind, at 6.6 m by 3.68 m, and took five workers 96 days to finish. That does not take into account the time spent on the design, which lasted eight months.

"We wanted to highlight our ethnic culture, but we also wanted new elements," explains Zhou Tengkao, who was responsible for designing the artwork. "We had five major revisions and finally settled on the dove, using it as a mosaic for a world map. In the lower part of the pattern, we adopted the images of the phoenix, the embroidered ball and the drum to represent Zhuang culture. Put together, it conveys the hope of all people in Guangxi for world peace and prosperity."

Zhuang embroidery, like most handicrafts, fell out of favor because of the intensity of manual labor. A small tapestry takes one worker three days to produce and sells for only 30 yuan ($4.43). Without counting the cost of material and with a worker making only a few hundred yuan a month, the sale price cannot offset the cost.

Zhuang is China's largest ethnic group, with 17 million people. Guangxi is officially called Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, and preserving this tradition is more important than making economic sense out of it. In rural Guangxi, a bride has to include an embroidered quilt in her dowry. Young women would give small pieces that they wove for their loved ones as a token of love, especially at the songfest, an important local festival. Even though the days are long gone when every family had a loom and every woman could weave, in Binyang, a town one hour from downtown Nanning, a factory still weaves yarns the old-fashioned way.

|

The largest Zhuang embroidery of its kind is on display at the Shanghai Expo, incorporating images of a dove and a world map. |

In the outer room, there are seemingly machine-powered looms, each manned by one female weaver. A wall of single-color yarn faces the worker. The wooden shuttles have an elongated hole in the middle, where threads of various colors are housed. Despite the look of automation the looms are operated by the worker.

How does she know when to use color and which color? The pattern of the tapestry is determined beforehand, which become cardboard slates with small holes in them, called the heddle or harness. The yarn passes through its eyeholes. It moves forward as the fabric is woven. But the details about the colors have to be memorized by the weaver.

"It takes two or three months to remember one pattern," says a weaver surnamed Huang. "If you make one mistake, you have to go back and fix it."

In the inner room, even the facade of machine operation is gone. The loom is exactly the same as it was hundreds of years ago. Instead of a stack of cardboard, now we have a bamboo basket overhead that holds the single-color yarn. Besides the rugged look, it can weave a fabric of half a meter, about half the width as the "machine" kind.

|

The modern loom is still powered by hand, but yields wider tapestries. The modern loom is still powered by hand, but yields wider tapestries. |

Here, weavers sit instead of standing. They have a band that holds their waist. "This job not only strains the eyes, but is hard on the back," Huang says.

The brocade presented at the Shanghai Expo required six weavers to work simultaneously and at exactly the same speed. If one gets it wrong, everyone has to go back to the same place to fix it.

"All this was done in a workshop with no air-conditioning," says Tan Xiangguang, who led the project in a 12-hour-a-day weaving marathon.

Tan, 55, started her weaving career at the age of 16. "We had to cooperate as if were just one person," she says. "Traditional yarn looks coarse and easily breaks when used as the longitudinal thread. This time we used something stronger and more refined, and it yielded a pattern that is smoother."

Tan wants to use this seamless brocade to bring the world's attention to her hometown and to have more people love this unique form of ethnic craft. In ancient times, the local legend goes, it was a fairy goddess who discovered the beauty of Zhuang embroidery: There was a Zhuang family of a mother and her three sons. The mother was a skillful weaver. She was working on a brocade with a house, a garden, an orchard, some farmland and some farm animals.

A gale swept the brocade away. It turned out the fairy goddess wanted to learn the craft of Zhuang embroidery. The mother dispatched her sons, one by one, to search for it. Both the eldest son and the second son ended up taking trips elsewhere and forgot their mission. The youngest son endured highs and lows and finally found the fairy goddess in a red dress. She was imitating the pattern of the embroidery and was not ready to return it. The son snatched it away and rode home.

Unbeknownst to him, the goddess had woven her own image into his mother's work. When he arrived home, the landscape in the pattern grew larger and larger, turning into a life-size farmland with all the images becoming real. That included the red-dressed fairy goddess. And she and the youngest son wed, living a life of rustic happiness ever after.

Many visitors to the Shanghai Expo who get a glimpse of this tapestry will surely fall in love with Guangxi, its people, its crafts and its landscape.

Huang Zhaohua and Zheng Yan contributed to this story.