Life and Leisure

Custom-made culture

By Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-05 11:45

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Villagers at Xijiang, Guizhou province, stage a grand show of their history featuring brilliant folk attire and rich customs at the central square. Photos by Erik Nilsson / China Daily Villagers at Xijiang, Guizhou province, stage a grand show of their history featuring brilliant folk attire and rich customs at the central square. Photos by Erik Nilsson / China Daily |

Tourism has helped the Miao ethnic group preserve their culture and traditions and brought a new awareness of their cultural identity. Erik Nilsson reports

Xijiang's "drum people" say they march toward modernity to the rhythm of tradition. Most of the 6,000 residents of the world's largest Miao village in Guizhou province - known for the belief that their ancestors' souls dwell inside percussion instruments - say tourism has spared them from becoming migrant workers. Consequently, they can remain in the settlement and live according to local customs. "Many people who went to work in cities have been coming back," 35-year-old guesthouse owner Li Zhen says. "After living outside, we have a new awareness of the importance of our ethnic culture and of ways to preserve it."

Li left in 1997 to work for two years in a Shanghai textile factory, where she earned 1,000 yuan ($148) a month.

"When I returned, life here was as hard as it was in Shanghai," Li recalls. "But things got better once Xijiang's tourism took off over the last few years."

The accelerated momentum of the village's tourism development has been largely propelled by provincial government investment. Xijiang's location on the fringes of Leishan county, which is about 260 km to the east of the provincial capital Guiyang and lures holidaymakers with its bullfights, cockfights and dogfights, has also proved a boon.

In 2007, Li built the first of the settlement's 50 nongjiale (rural resorts) with 400,000 yuan she borrowed from the bank, and which she has already repaid.

"We serve guests, but they serve us, too," Li says. "Life's good now."

Leishan county publicity bureau chief Huang Liangzhong explains Li's story is typical of Xijiang.

"This is the home of Miao culture, but many people left after reform and opening up," he says. "However, tourism's development has brought most of them back."

Among the county's population of 150,000 in a national census of 2003, Miao, Shui and other ethnic groups take up more than 123,000.

Still, as painter Li Yufu points out, the newfound prosperity that funds the preservation of tradition also impacts on it in other ways.

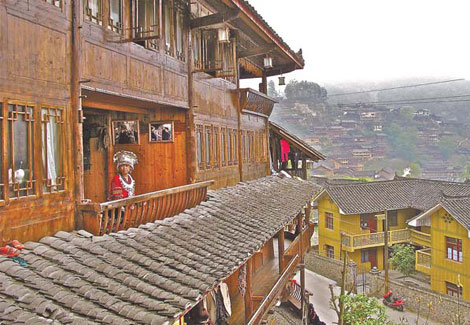

While preserving ancient wooden houses, Xijiang villagers have built many guesthouses to meet the growing demands of tourists. |

"Modernity has a strong influence on our customs," the 41-year-old says. "Putting on so many performances leaves us with little time to just live our lives."

He explains that because the Han Spring Festival overlaps with the Miao's around February, the tourist rush keeps local people too busy to celebrate.

The upside is that while villagers can't enjoy much time observing customs with family and friends, they get to show them to outsiders, and earn considerable income.

Certainly, the cultural exchange starts from the moment visitors arrive and are greeted by male lusheng (a polyphonic bamboo flute) players and women vocalists singing ancient songs of welcome.

The women's chorus lifts hollow water buffalo horns brimming with rice liquor to the lips of travelers, who must guzzle the entire "cup" if they touch it with their hands. Those who decide to grab the bull by the horns and take the challenge beware - the largest of these vessels can contain up to 1 kg of the alcohol.

Such ceremonies are staged not only to show hospitality but also to ward off bad luck, as failing to host the boozy reception is thought to invite evil fortune.

Miao people are good at making lovely music with plain looking leaves. |

This belief flows from the powerful undercurrents of mysticism that determine the course of life in Xijiang, whose first settlers are said to have arrived some 600 years ago.

Local lore holds that one must undress upon encountering a snake shedding its skin, for instance, and that illnesses are cured by pouring fowls' blood on the sacred bridges found outside every home.

Another testimony to spirituality's importance in Xijiang is the zangtou, or shaman, who is responsible for deciding the planting and harvest season dates, and auspiciously starting festivals by sacrificing a pig.

The title is passed from father to the youngest son, but villagers can vote out a bungling zangtou or vote in a promising successor if the sorcerer sires no male offspring.

Xijiang's zangtou Tang Shoucheng says he is happy to have a 9-year-old boy to inherit his station.

Tang doubles as the local math teacher, so, in addition to teaching the community's youth number tricks, he's also teaching his son secret spells long passed down their lineage.

Tang says he's happy local tradition has not only survived modernization in Xijiang but also is being presented to the world at the Shanghai World Expo's Guizhou Pavilion. He believes the Miao should not only perpetuate their customs but also share them with the others.

"I want to go to university to study history, culture and tourism," he explains.

"After graduation, I hope I can return to Xijiang to contribute to Miao customs' preservation and advancement."