Life and Leisure

In this life and the next

By Zhu Linyong (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-11 11:28

|

Large Medium Small |

|

The Living World series, painted wood, by Ju Ming on display in the National Art Museum of China. Photos by Cui Meng / China Daily |

Artist Ju Ming says he enjoys sculpting so much that he will never stop, which is good news for his many fans, Zhu Linyong reports

The largest solo mainland show of works by Ju Ming, arguably Taiwan's most influential sculptor, is currently running at the National Art Museum of China.

On view are 150 larger-than-life pieces of his Living World series, works Ju has produced over the past 30 years in a wide range of media, including wood, stone, ceramics, bronze, sponge, styrofoam and stainless steel.

At the entrance to the museum, viewers will encounter two of Ju's humorous works - a group of brightly colored, stainless steel paratroopers suspended in mid-air, and a queuing crowd comprised of copper-cast individuals with varied facial expressions.

Ju's works occupy four exhibition halls, featuring a myriad of figures, such as fashionable young ladies, gossiping crowds, ballerinas, soldiers, monks and swimmers, all wrought in a minimalist approach.

The exhibition also debuts Ju's most recent, philosophical works, entitled Imprisonment, as part of the Living World series.

The ongoing exhibition offers local viewers "a window to another domain of Ju's masterful art", says museum dean Fan Di'an.

Ju's first successful solo show was held in the same museum in 2006, featuring his Tai Chi sculptures - his signature works - which are popular in public spaces in Taiwan, Hong Kong and many other cities around the world.

In Fan's view, the contemplative and spiritually charged Tai Chi works reveal Ju's perfect combination of modern sculptural language and ideas from Eastern aesthetics.

But Fan says Ju's Living World series not only "demonstrates a maestro's prowess in the use of materials, it also expresses his sharp observations of reality and his humorous, optimistic outlook on life, and overflowing, child-like innocence".

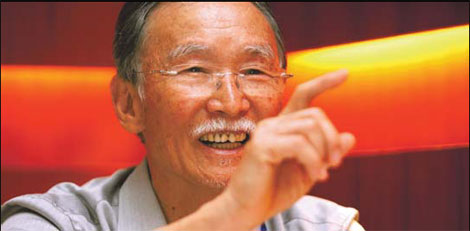

Wearing a work cap, the thin, short and brisk 73-year-old artist impressed local viewers with his unassuming and easy-going demeanor at the recent opening of the exhibition.

"This time, I have brought to you a whole new set of works. I hope you'll like them," Ju said simply at the opening, casually waving his right hand.

"Ju has been known as an exceptionally persistent, challenge-loving artist, who, despite many twists and turns in his life, has pressed on with courage and brought one delightful surprise after another to enthusiasts of his art," said Su-mei Wu, executive director of Taipei-based Juming Culture and Education Foundation.

"Sculpting is happiness, which is why I've been doing it for decades," Ju said. "But of course, hard work is the other side to it."

Taiwan's most influential master sculptor Ju Ming visits Beijing. |

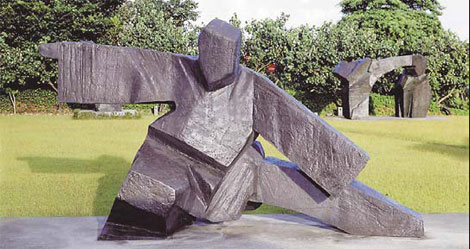

Single Whip from the Tai Chi series, copper, by Ju Ming. |

Ju always quotes the following lines as advice to the younger generations of artists:

"With effort, even an ugly duckling can become a swan. People relying on their cleverness to avoid hard work always get distracted by their own cleverness in the end."

"For the slightly stupider among us, we have no other option but to keep on working," Ju explained. "As long as one is hardworking and determined, he will succeed. Absolutely. Those who fail are the ones that do not have the perseverance."

Ju himself is a good example of this.

The artist, originally named Ju Chuan-tai, was born into a poor peasant's family in Miaoli county, Tongsiao, in 1938, in the waning years of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan. He was the 11th child in his family.

Now ranked among Asia's most preeminent sculptors, Ju showed his artistic talent as a teenager.

He drew ancient heroes with gusto, and his sketches were regularly displayed on the walls of the family home.

Looking at them, villagers shook their heads, marveling at his mastery of such skill without having received instruction.

At that time, Ju had to combine study with labor, herding cows and sheep after school. He spent his childhood preoccupied with finding enough food to eat.

At 13, Ju got his one and only academic diploma. Afterwards, he helped to support his family, working as a clerk in a grocery store.

At 15, Ju became an apprentice of veteran woodcarver Lee Chin-chuan.

Trained to carve traditional religious and historical motifs, Ju quickly acquired an impressive technical proficiency. He soon opened his own workshop teaching students. Yet despite such achievements, skill alone was not enough.

"What I learned then was how to manufacture those traditional wood carvings, which can found in temples. However, I wanted to be an artist rather than a small-town craftsman," Ju recalled.

During his leisure time, Ju tried to create works that he considered art and he entered them in competitions.

His initial attempts failed. But he kept on trying and eventually his works began to be accepted for exhibitions and even won prizes.

By then, Ju had come to see that he could only develop further as a sculptor if he re-apprenticed himself, this time to Taiwan's pioneering modern artist Yu-Yu Yang.

Yang agreed, impressed by "Ju's flowing lines through the natural grain of the wood, the form executed with such an assured gentleness and humility".

Ju's first solo exhibition was held in March 1976 at the National Museum of History in Taipei, thanks to Yang, who convinced the museum authorities to show his student's pieces.

The works displayed at the exhibition included sculptures of water buffaloes, an important symbol of Taiwan's country life, and historical and legendary figures, rendered in a rustic and simple manner.

With their articulate forms and sincere expression of feelings, the sculptures had a power and charm that immediately captured the attention of the local art community and media.

As a result, Ju became a prominent figure in the back-to-the-roots movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, when artists in Taiwan began saying no to the idolization of Western-style art and started looking for something more in touch with their life and culture.

But, despite his unprecedented success with native imagery, Ju was not content.

Ju had begun practicing tai chi, on Yang's advice, in order to develop physical and mental discipline. He believes he benefited immensely from this practice and gradually started thinking about sculpting works on the theme of tai chi, which had never been done before.

More abstract than his previous native-flavored works, his Tai Chi series consisted of large, monumental wood and bronze sculptures.

He carefully studied each movement and posture of tai chi before he rendered them, fully expressing in simple forms tai chi's spirit of calmness, stability and strength.

The Tai Chi series garnered rave responses from foreign viewers when shown abroad, but provoked harsh criticism at home. People impressed with his previous works, scolded him as "having stepped away from tradition".

However, the criticism did not stop him from seeking new challenges.

"I can take tai chi only so far I like to innovate. When I sculpt tai chi, the postures and spirit of tai chi must always be brought out. This means than I am not given free reign," Ju later explained.

Just like his Tai Chi works, each figure in the Living World series is minimalist - a carved line for a nose, two for the eyes, a circle for a mouth. Yet every character seems to be alive and telling a different story of modern-day living.

Tai Chi and the Living World series have earned Ju a worldwide reputation and pronounced him a master of figurative art, noted art collector and curator Chang Tsong-zung says.

Ju has forged a sculptural language of his own. And with the ever-transforming appearances in the Living World series "came multiple breakthroughs in terms of external artistic morphology", Taiwan art critic I-ming Chen says.

Meanwhile, Ju has continued to make his art more inclusive and conceptual. His latest Imprisonment works deal with the subtle distinction between good and evil, other-imprisonment and self-imprisonment, freedom and its limits. As Ju himself proclaims: "I will keep working on the Living World series until I grow old, because it is so interesting and there is so much to present. In fact, I will want to keep doing it even in my next life."