Life and Leisure

Say cheese!

By Mike Peters (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-16 13:51

|

Large Medium Small |

A Dutchman is carving out a niche for artisan cheese in China. Mike Peters chews the curds.

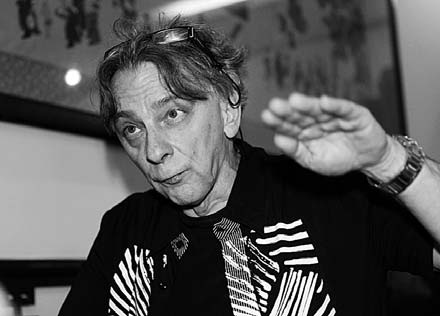

Marc de Ruiter inspects Gouda cheeses in cool storage. Each dated cheese is cleaned by hand every week. Mike Peters / China Daily |

TAIYUAN - Entering Marc de Ruiter's workplace is not like visiting a typical businessman's office. We first pull white smocks and trousers over our clothes, like doctors or nuclear-lab inspectors. Then we stuff our feet into big white rubber rainboots. Finally, a grinning assistant hands out stiff white hairnets.

When de Ruiter is satisfied that we are covered head to toe, he opens a heavy door and waves us through. Tentatively, we enter his world of cheese-making.

For foreigners in China, Yellow Valley Farmhouse Cheese can be a song from home. Western-style cheeses are not part of China's food tradition and expats who grew up with sharp cheddar, savory Gouda or creamy Camembert can get homesick after a few weeks in a land with fewer and blander styles of cheese.

When you meet de Ruiter at a big-city trade show, his hand-sized packages of artisan cheese in bright yellow cellophane gleam like works of art. Here in rural Shanxi province, about 45 minutes' drive from the capital, Taiyuan, there is as much science as art.

"Cheese-making is about chemistry," says de Ruiter, a Dutchman who has worked on agricultural development projects in China for 13 years. He points to a huge vat, where two giant paddles stir temperature-tested whole milk with robotic precision.

"The challenge is: How do you get all of the solids together?" Low moisture, he says, means longer preservation for the final product. "Number one: Good hygiene is essential," he adds.

Milk curds collected by the stirring paddles are packed into bowls, which are stacked five-high and pressed to squeeze out as much water as possible. Once the cheeses are shaped into thick disks, they proceed first to a salt bath and then to a refrigerated room, where each one is labeled, dated and set out on wooden shelves to mature.

"Every cheese has a cheese mark," he says. "That number means traceability. From that I can tell when it was made, which farmer's milk was used, who made it here in our shop. This is what you need to have food safety standards."

Such standards are vital in an industry that has struggled with image problems since China's infamous melamine milk scandal made headlines a few years ago.

"I don't believe there is one small farmer who added melamine," de Ruiter says. "This happened at the big producers, where the pressure of price meant people were always looking for ways to lower cost of production." Eventually, that meant cows were underfed, and the resulting milk lacked protein. That led to another shortcut: Adding the chemical melamine.

"That was a national, industrial failure of quality control," he says. "People got too greedy."

When the resulting crisis led farmers to dump their unmarketable milk into the streets, de Ruiter took up the challenge.

In 2003, he says, creating a market for cheese was another way for his non-governmental organization (NGO), US-based Evergreen, to help small-scale farmers.

His group's previous efforts focused on broccoli and pigs.

"We spent two years on vegetable trials in five villages before we contracted labor to raise broccoli," he says. "Farmers don't like change, and at first they resisted because they didn't like to eat broccoli themselves. So we had to show them the market beyond the horizon: We took them to Taiyuan, less than an hour away, where supermarkets were getting a good price for broccoli."

Pigs presented a similar opportunity for the NGO to study local ways and see how they could be teamed with modern technologies. "Farmers weren't making any money raising pigs, even though there was plenty of demand for pork," de Ruiter says. While price was one issue, poor housing and feeding methods - and the wrong breed for commercial demand - were all part of the problem.

"The traditional black Chinese pig that rural people love to raise and eat wasn't attractive to city slaughterhouses," he says, ticking off the issues with his fingers. "Too much hair, too much fat, not enough red meat, so the traditional pig was harder to process."

The black pig also needed six to eight months to get to market weight, de Ruiter says. "New breeds only need four months to mature, so you get two cycles a year instead of one. One kilo of meat takes less feed and less time to produce."

Once farmers started seeing themselves as businessmen, he says, the numbers were very convincing.

With those experiences under his belt, de Ruiter was eager to help dairy farmers develop more sustainable ways to produce milk. But this project was a little more personal for the Dutch expat: "I also just really wanted some good cheese," he smiles.

So Yellow Valley Farmhouse Cheese was born, and de Ruiter and his team started reaching out to expat-oriented markets and chefs.

But first, they made cheese. Farm families are coaxing milk from cows by 6:30 am, and 90 minutes later the "white gold" is being hauled by truck to the cheese-maker.

"We pay farmers well, about 20 percent higher milk prices than they can get elsewhere," he says. "There's no middleman, so the farmer gets about a 40 percent higher profit margin."

"I know all of the farmers that sell me milk," he says.

And while Yellow Valley's artisan-style Gouda - in original, garlic, spicy Italian and Provencal herb flavors - is still an experiment for Chinese consumers, de Ruiter believes their appetite for the foreign foodstuff is growing.

"And as we all know," he says, "the best food in the world is local, wherever you are."