Life and Leisure

Staging transformation

By Chen Jie (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-17 13:34

|

Large Medium Small |

The dramatic changes undertaken by the country's previously leading arts performance troupe testifies to the impact of reform. Chen Jie reports

New performers hired from the Beijing Academy of Dance after the reform of the China Oriental Performing Arts Group take a break during rehearsal. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

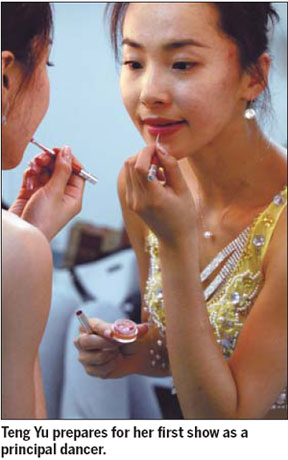

Teng Yu carefully paints her eyes in the Poly Theater dressing room, exactly as she has done for the more than 300 times her troupe has performed the dance they will repeat tonight.

But this Friday evening's show will be different in that Teng will take the stage as the principal dancer for two numbers - something that was impossible before last November, when the China Oriental Performing Arts Group undertook reform in line with a comprehensive revamping of the country's cultural industries.

Under the complicated system previously in place, the tall, slender 27-year-old was excluded from assuming such a rank until age 33.

"Nervous? A bit," she says, shifting her eyes from the mirror for a moment before powdering her cheeks. "Actually, it's more like excited. I'm expected to perform the leading role and believe I can do it well."

Seated beside her, Teng's 29-year-old colleague Wang Ziding expresses her envy with a laugh.

"You're lucky. But we'll have opportunities, too," Wang says.

Before the reform, dancers joined the company after graduation, usually at around age 20.

After yearlong internships, they could become Level 4 dancers, progressing to Level 3 four years later and Level 2 in another four. A talented Level 2 performer could become a principal dancer within a few years, but there was no guarantee.

The reform, which began when the State-owned ensemble reinvented itself into the China Oriental Performing Arts Group last November, has created flexibility among the tiers. Teng was a Level 3 dancer last week.

The new system is intended to promote young talent, enabling the best and most ambitious to take center stage. It also allows older members to assume less responsibility if they wish and those who would rather work backstage to do so.

Wang has been sent to the Communication University of China to study recording and broadcasting because the group needs technical staffers for a broadcasting team it plans to start.

Late Premier Zhou Enlai initiated the Oriental Song and Dance Ensemble in 1962, which brought together leading artists from around the country. At a time when few foreign troupes toured China, the ensemble specialized in Asian, African and Latin American folk songs and dances. Its instrumentalists were skilled with both traditional Chinese and foreign instruments.

Some members, such as Zhu Mingying, Zheng Xulan, Li Guyi and Cheng Fangyuan, were once idolized like today's pop stars.

The ensemble also won international acclaim with its overseas tours and was regarded as a cultural ambassador.

But the proliferation of new troupes following the opening up and reform that began in 1979 created mounting competition, ousting the ensemble from its top spot in the early 1990s.

State-owned performing arts companies mostly remained closed to the market, while other social sectors underwent reforms. Ensembles suffered from the outdated career advancement system's rigidity, which sapped performers of motivation and passion.

Young members desperately waited for veterans to retire. Upon finally becoming principal dancers in their late 30s, they found they had passed their prime. Many decided not to waste their time and left. Such an ineffective system hurt revenues, the company's leadership says.

"The ensemble's name is golden but that didn't mean it was profitable," says Gu Xin, whom the Ministry of Culture appointed general manager of the Oriental Performing Arts Group last November.

Gu was initially hesitant to take the post. He already had a successful career as the cultural bureau director in Jiangsu province, and the dance group was riddled with problems, he explains. "I convinced myself the company would offer a much bigger platform for pushing forward the reform of cultural sectors throughout the country."

Since assuming the post, he has called more than 50 meetings to discuss solutions and also has spoken to more than 200 members about their concerns.

Many were worried that the reform would affect their income. For decades, the ensemble was mainly supported by government subsidy. Social welfare laws provide higher pensions to those who retire from these government-subsided institutions than to those who retire from companies.

To alleviate this anxiety, the group buys double pensions, and provides medical and unemployment insurance, and a housing allowance.

Members who are too old to compete for spots on stage can assume new positions at the new training center, or in areas such as management, marketing or human resources. All 484 performers had signed contracts with the group before May.

Production department director Song Bingfu says that before the reform, the shortage of regular shows meant less than 20 of the vocal team's singers were able to perform, as were less than 20 of the 73 instrumentalists.

"Many received a salary from the ensemble every month but only did outside work," Song says.

The group now produces more commercial shows, in addition to two daily performances at the Shanghai Expo, enabling all qualified members to appear on stage.

And it has needed to recruit more than 20 new dancers from the Beijing Academy of Dance for contract shows.

Gu, who is also a juror on this year's CCTV National Young Singers Contest, also discovered new talent during the competition and has signed three award-winning contestants. "We need a lot of new blood while reviving veterans' passions," Gu says.

Wang Yang says he was satisfied when moved to the marketing department after a broken leg forced him off stage in 1999. "My salary was around 1,000 yuan ($147), plus 350 yuan per show. We had only a few shows every month," the 38-year-old says.

His salary increased substantially when he moved into marketing, where the workload was relatively light.

But dancers' incomes multiplied after the reform, when Wang Yang became associate director of production, a job requiring more work for less money than his former marketing post. However, he says he is still content with his new spot because the work is interesting.

"Our work in management and marketing is challenging," Wang Yang says. "I have much to learn as a retired dancer without any professional training in (these areas)."

Wang Yang briefly returned to the stage at Poly Theater last weekend, since the Expo shows had created a shortage of dancers in Beijing.

He says the company had done some 150 shows this year before August - triple the number of previous years.

Performers' average salary has increased to 7,000 yuan ($1,030) a month, plus extra for every show in which they appear.

Group dancers can earn 111,000 yuan ($16,300), and principal dancers, such as Teng, expect 300,000 yuan this year.

The group is also planning to found a musical team and is hunting for a location for its Grand Oriental Theater.

"We are ambitious to construct China's entertainment giant, and the shows would only be part of our business," Gu says.

"A company can't rely on ticket revenue. We must create as much added value as possible to translate our golden name into golden returns."