Focus

Writing on the wall for guns

By Hu Yinan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-18 14:27

|

Large Medium Small |

|

More than 1,700 firearms are destroyed by police in Guiyang, capital of Guizhou, in this file photo taken in 2008. Wu Dongjun / for China Daily |

A clandestine market for unregistered weapons still exists despite crackdown. Hu Yinan reports from Hunan.

Adeadly trade is openly advertised on a graffiti-adorned wall. Situated close to a bridge connecting southeastern Chongqing's Hong'an township with Biancheng, the popular "frontier town" of western Hunan, the graffiti does not depict artworks or slogans but instead advertises the contact details for illegal gun traders.

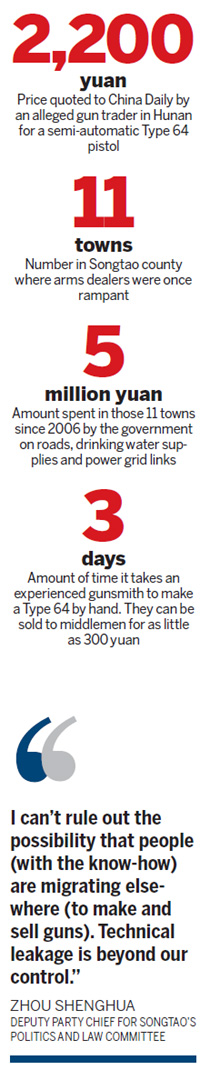

After calling one of the numbers written on the wall the phone was answered by what sounded like a middle-aged male speaking in a heavy Hunan accent. He promised that for 2,200 yuan ($320) he could deliver a Type 64 - the semi-automatic pistol still used by police forces across China - to a chosen location. Like any good salesman he was quick to make his pitch and offer added value.

"It comes with a silencer and five free bullets," he said.

Delivery was dependent on 500 yuan being deposited into his bank account and once this was confirmed a black Volkswagen Santana with Qinghai license plate would pick up the buyer and take him to nearby mountains where he could test the weapon.

Neither the car nor the bank account would reveal his true identity, the trader insisted.

"Don't bother checking," he warned. "The car was stolen and the ID card I used to set up the bank account was fake."

After reporting the conversation to police on both sides of the border, officers said the sale was probably a hoax and explained that no action can be taken unless a suspect is actually caught doing business.

In this remote mountainous region of Southwest China - where owning a powder shotgun was a tradition among the Miao ethnic people until 1996, when the central government introduced legislation banning the buying, selling and transporting of firearms without official permission - the market for guns is yet to disappear.

No official statistics are available on the number of privately owned firearms.

In 2007, a study by the Geneva-based Graduate Institute of International Studies estimated the total number of guns held by civilians in China at 40 million, third only to the United States and India. Chinese analysts, however, say the figure is a wild exaggeration.

Today, about 2,100 self-proclaimed Biasha people in Bingmei, a town in Guizhou province, claim to be the only civilians in the country who can legally possess guns (powder shotguns with no bullets, that is). Tourism has been the tribe's pillar industry since 1999 and a team of about 80 gunmen put on a traditional performance for visitors every day.

"The shotguns are just used as props, nothing more," said team captain Gun Yunliang, 40. The performers earn around 300 yuan a month from the shows.

Some 500 kilometers north of Bingmei, where shotguns were confiscated in large quantities and "gun performances" are outlawed, the arms trade has instead flourished.

In the 1990s, Songtao, a highly impoverished county in Guizhou, emerged as one of China's most famous homes to the gunsmith (the others, also poor counties with significant non-Mandarin-speaking populations, are Hualong in Qinghai province and Hepu in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region), according to Long Wenyu, 36, captain of the Songtao public security bureau's gun taskforce.

Triangle of trade

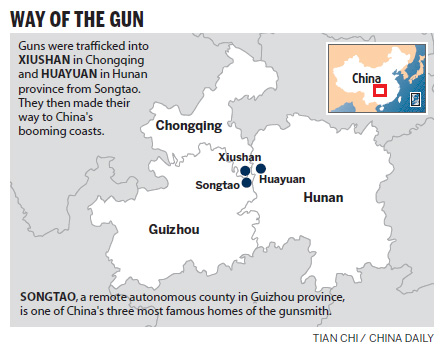

Songtao is less than two hours' drive from both Xiushan in Chongqing and Huayuan in Hunan. Historically beyond effective government control, the three counties span highly complex terrain and are all roughly within 500 kilometers of a major city.

Until 2006, the trio formed an underground gun-trading triangle, where illegal firearms made in Songtao were trafficked into Xiushan and Huayuan and then to China's booming coastal cities, said Li Ling, chief of the Chongqing public security bureau's criminal police unit.

Within the region, particularly in Huayuan, guns were popular with gangsters controlled by private mine owners, said Long Wenyu. His unit, the first of its kind at the county level, was set up in October 2004, when authorities in Guizhou vowed to curb gunsmiths and traffickers by 2006 and ensure no further backlash in 20 years.

And so far the county has done just that, according to Zhou Shenghua, deputy Party chief for Songtao's politics and law committee, which oversees law enforcement.

"The situation has for the most part been contained since 2006," he said. "Our current focus is on the promotion of relevant policies to villagers and prevention of any possible backlash."

To aid that effort, officials were last year assigned to head up seizure operations in nine of Songtao's 11 towns where arms dealers had been thriving. All hostels, lathe workshops, hardware stores, electrical welding companies and metal recovery units were incorporated into a surveillance network, said a statement provided by the county police.

Public security bureau officers in Guiyang, capital of Guizhou province, display the more than 1,700 illegal guns and 5,000 knives seized in 2008 at Guiyang steel factory before destroying them. Wu Dongjun / for China Daily |

|

A resident rests beside a wall daubed with the numbers of people offering guns for sale at the Chongqing-Hunan border. Hu Yinan / China Daily |

Taskforce captain Long Wenyu shows a handmade Type 64 gun. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

The officials, who appear as deputy town leaders, and a team of 48 law enforcement officers and former servicemen are also responsible for helping alleviate rural poverty, which the government sees as a direct cause of the gun industry's popularity.

Assembling a handmade Type 64 takes an experienced gunsmith only two to three days and costs around 300 yuan, yet several transactions by middlemen can push the sales price up to more than 10,000 yuan in places such as Shenzhen, an economic hub in Guangdong province.

"In two to three days, these gun traders make more money than we do in a month," joked a gun taskforce member who did not want to be identified.

For farmers, whose annual earnings are typically in the high hundreds, gun money can be a big boost.

Despite recording a 19.5-percent average growth for the past three years, Songtao's gross fiscal revenue in 2009 was just 335 million yuan ($49 million) - a pitiful 1.2-percent of the gross fiscal revenue over that same period in Jiangyin, a prospering county in Jiangsu province.

About 47 percent of Songtao's 690,000 registered residents are from ethnic minority groups and many older than 40 cannot speak Mandarin, said deputy Party chief Zhou. The language barrier, in turn, ties people to their land and strips them of the opportunity to find more profitable work away from home.

Around 100,000 people in Songtao still live in poverty, while the rural per capita net income last year was just 2,504 yuan, county government figures showed.

"The profits from selling guns (in comparison) is simply too tempting," added Zhou. "There's always going to be people willing to take the risk."

When Wu Bike could no longer afford a high school education in the wake of his father's death in 1998, he said making guns seemed to be a reasonable option. The oldest of three sons and the family's sole breadwinner, Wu learned to assemble Type 64 pistols after taking apart imitation guns (also illegal in China).

"I never gave it much thought. All my friends did it," he told China Daily.

Soon after, Wu and three of his friends - all farmers in Songtao's Daxing township - were caught by police in his cellar, where they had just sold a handmade Type 64 to a middleman for about 500 yuan. Wu was sentenced to four years in prison but it did not take him long to pick up where he left off.

In the summer of 2002, just months after his release, police again raided Wu's house and found about two dozen gun parts.

As the number of parts was lower than 30, the legal requirement for a prison term (a Type 64 pistol is made up of 32 to 33 parts), he was given three years of re-education through labor.

Wu returned home in 2006, when county authority began shifting its gun-control policies toward poverty alleviation after a substantial reduction in gun crime. Two years later, officials offered him 100 free pigs (and 50 yuan in subsidies for every sow) to start a farm. He credits the move with helping him to settle down and get married and, today, his hopes are on his 1-year-old son.

Songtao authorities have since 2006 spent roughly 5 million yuan on roads, drinking water supplies and power grid links in the 11 towns where gun crime was rampant (officials say the arms trade has all but been wiped out in five of them). More than 900 people also regularly receive financial aid.

Yet, residents say the money is still falling short.

Wu's home still has no running tap water and he is struggling to break even by breeding pigs. Although his days as an underground gunsmith are over, he admits that is only because he "dare not do it anymore".

Shooting stars

The mass gun seizures have also had an effect on the rural balance. Since rural shotguns were confiscated, the number of wild boar has soared, causing harm to farmers and their land, said a member of the gun taskforce who did not to be named.

Deputy Party chief Zhou acknowledged, however, that the main challenges with gun seizures remain economic ones.

"I can't rule out the possibility that people (with the know-how) are migrating elsewhere (to make and sell guns)," he said. "Technical leakage is beyond our control."

The ability to manufacture guns, which some learn from older generations and others through work experience, is something people are usually keen to hold onto, said taskforce captain Long.

"The graffiti ads are almost never for real; the actual makers and dealers don't put things out in the open," he said. "There has to be enormous trust between the parties involved in the (gun) business. That's why it's always done in local circles, through friends and relatives."

The gunsmiths have long since gone underground, said Long, with some farming during the day and making weapons in remote hillside caves at night.

With a heavy reliance on kinship and blood ties, the gun taskforce has been keeping a close eye on the sons and nephews of veterans in the business. However, some have managed to pass their knowledge onto outsiders through their daughters "as wedding gifts", added Long.

All nine officers on Songtao's anti-gun taskforce are from minority ethnic groups (four are fluent in the Miao dialect) and have at least a decade of experience with the police.

"My squad's efforts have helped contain the local gun trade to the point that most residents dare not make guns anymore," said Long, an ethnic Miao and the longest-serving member of the team. "I promise you, we also catch about two-thirds of all people who come here wanting to buy guns."

Despite the clampdown and coordinated surveillance throughout the triangle, however, there is still room for the gunsmiths, dealers and prospective buyers to do business.

Zhou blamed the fact that similar anti-gun endeavors in Chongqing and Hunan have not been as consistent as those in Guizhou.

In Xiushan, a senior publicity officer with the police bureau who did not want to be identified said gun seizure operations "were the focus of last year's campaigns". He declined China Daily's request for an interview.

In January last year, Chongqing authorities launched a televised crackdown on illegal firearms that involved 1,000 police officers and paramilitaries armed with bazookas. Security bureau officials said the campaign resulted in four underground arsenals and 10 weapon stores being destroyed, and the detention of dozens of suspects, all of whom were from Songtao.

Meanwhile, in rural Biancheng, China Daily reporters discovered it is still easy to buy 7.62 mm caliber seamless steel barrels, an essential part of a wide range of revolvers, pistols and rifles.

He Li, deputy director of the Ministry of Public Security's firearms division, previously said the barrels of illegal firearms were usually purchased, rather than homemade. However, although the barrels have no civilian usage, their manufacture and sale are not covered by the law, he said.

"We can refine everything here, so long as you bring the steel," said a woman surnamed Yang, who runs a small family hardware store in Biancheng.

Yu Chenkang and Hu Yuguang contributed to this story.