Life and Leisure

Artistic merit

By Mu Qian (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-08-18 14:36

|

Large Medium Small |

The tradition of producing Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings has ensured a decent quality of life in a remote village in Qinghai province. Mu Qian reports

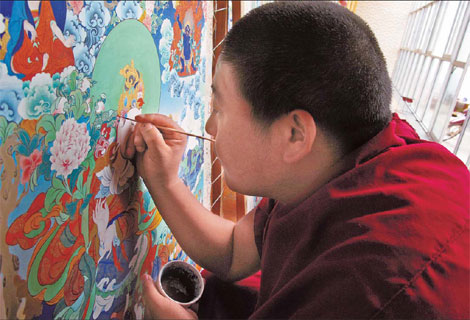

Lama apprentice Drupa Dargye works on a thangka at the Snowland Art Center of Wutun. Photos by Mu Qian / China Daily |

In stark contrast to most of the country's villages, none of Wutun's young people have left to work in the city. That's because this settlement of about 2,500 in Northwestern China's Qinghai province already has its own more lucrative version of assembly line work - that is, producing thangka (tangka), or Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings.

It's a trade plied by nearly every man in Wutun. And it's estimated that more than half of the thangkas in the country are produced in the village, including many in such prestigious monasteries as Tashilhunpo, Tar and Labrang.

Most thangka instead end up in private homes. Depending on size and quality, they can fetch a few hundred yuan to more than a million a piece for their creators.

"There are so many orders that I can't possibly finish them and have to let my students help me," painter Nyangbon says.

Wutun, which is located in Huangnan Tibetan autonomous prefecture's Tongren county, has sustained a tradition of thangka painting since the 15th century, when Tibetan Buddhism rapidly spread throughout the area.

Many monasteries were erected during this period, and the mix of Tibetans, Tu and other ethnic groups who lived in the area set about painting religious images to adorn them.

These skilled artisans also traveled throughout the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, painting as they went.

But it was only a few years ago the folk art came to offer a viable way to make a living.

Nyangbon says there were fewer than 100 people in the village able to paint thangka when he began studying the art form in the early 1980s, during which time Buddhism reemerged after being forbidden during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

When Nyangbon opened a small thangka shop in Lhasa in the 1990s, a 70-cm-by-55-cm painting sold for 500 yuan ($57). The same work would today be priced between 5,000 and 50,000 yuan.

Nyangbon's personal record for a high-price sale came when he sold a work depicting the life of Sakyamuni for 1 million yuan ($147,160) in 2007.

His Regong Painting Institute last year grossed 12 million yuan, a figure already surpassed this year.

"The price climbs are related to the growing popularity of Tibetan Buddhism," Kartsegyal says.

"As more Han people begin to practice Tibetan Buddhism, thangka has become increasingly popular among a broader demographic."

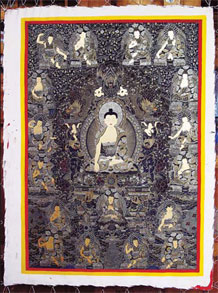

An unfinished thangka. |

Kartsegyal's market insight comes from his roles as deputy director of the Cultural Bureau of Huangnan Tibetan autonomous prefecture and as chairman of the prefecture's Folk Culture and Art Association.

Two of the main destinations for Wutun's thangka are Beijing, where more celebrities are following Tibetan Buddhism, and Shanxi province, home to the traditional Buddhist holy place Wutai Mountain, Wutun thangka artist Pande says.

"Many of the new urban rich are searching for a belief system and are attracted to Tibetan Buddhism, so they want a thangka in their house," Kartsegyal says.

"They don't care about the price, because bargaining would seem impious."

And the surging thangka prices are also caused in part by the recent trend in which artwork and antique collecting has become a fad.

The priciest thangka of 2002, for instance, was a Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) work featuring Samantabhadra that was auctioned for 55,000 yuan in Tianjin. Five years later, Beijing Council International Auction Company auctioned another piece from the same period for 896,000 yuan.

But today's collectors more often buy modern thangkas, because international institutions have already snapped up most ancient specimens.

The centuries-old tradition, once propelled by religious devotion, is now transforming to adapt to a market-driven society.

"There is no problem with making money as long as one still paints thangka with respect," Nyangbon says.

"I'm glad more people are buying thangka because they are accumulating merit by looking at the Buddha images."

In the past, Thangka painters wouldn't dream of putting their names on these objects of worship. But stamps have begun appearing on the works since they've become collectors' items.

And women are now getting in on the process of creation, once solely the realm of men.

Wutun thangka painter Chudrup was among the first masters to recruit women apprentices.

"Women's social status was very low in our village in the old days," the 40-year-old says.

"They weren't allowed to paint thangka. All they could do was farm," he continues.

"I thought this was unfair, so I started teaching them how to paint thangka 10 years ago. I hope they'll go on to teach more women."

Wutun still adheres to the traditional master-and-apprentice model for studying thangka painting. Because the art form is exceedingly complicated, it takes an average of six years before apprentices can strike it alone. Some take more than a decade.

Today, 91 apprentices are studying at, and 53 have graduated from, the Wutun Snowland Art Center, a training spot Chudrup opened eight years ago.

Limited space has meant Chudrup can only admit a small percentage of applicants. But the local government recently allocated a piece of land for him to establish a thangka painting institution able to enroll 1,000 students when it opens next year.

Also, Wutun's growing reputation is attracting outsiders to travel to the village to study the painting techniques.

Wang Shiyu, a 22-year-old Han Buddhist from Henan province, who has been studying thangka in Wutun for three years, says painting these works has a calming effect. Designer Yuan Yan, from Beijing, says she finds the techniques are very close to her ideal way of painting. She hopes to apply what she has learned from thangka in her future design work, she adds.

Tongren county's three artistic heritages - painting thangka and murals, crafting patchwork barbola and sculpting - are collectively known as the Regong Arts. They were listed on UNESCO's representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity last year.

The rising profile of Regong Arts has led the Tongren county government to consider swapping its official name for "Regong", the Tibetan moniker for the area.

From August 23 to 25, Tongren will co-host the third Qinghai International Thangka Art and Cultural Heritage Fair. The event will include exhibitions and a promotion of projects related to the local cultural industry.

"The thangka art of Tongren is a rich and practical resource for the improvement of local people's lives and for enhancing of the area's publicity," Kartsegyal says.

"What we need now is to figure out how to create a healthy environment in which the market will not drive the old art form to deviate from its roots."