Focus

Terracotta army emerges in its true colors

By Ma Lie (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-09 08:00

|

Large Medium Small |

|

German experts who specialize in restoring historical artifacts minutely examine a bronze waterfowl sculpture, excavated from the Mausoleum of Qin Shihuang, at Shaanxi Archaeological Institute in Xi'an, capital of Shaanxi province, in this file photo. Provided to China Daily |

China-Germany alliance has helped keep the glow on warriors' cheeks. Ma Lie reports from Xi'an.

The earth in the ancient city of Xi'an continues to astound archaeologists.

When excavation work to find more terracotta relics restarted for the third time last year in Xi'an, archaeologists admitted they did not expect to make any groundbreaking discoveries.

Researchers suggested that the No 1 pit, the largest of the three that surround the tomb of China's first emperor Qin Shihuang (259-210 BC), was in a worse condition than the other two and not likely to offer rich pickings.

However, the experts were more than happy to be proven wrong.

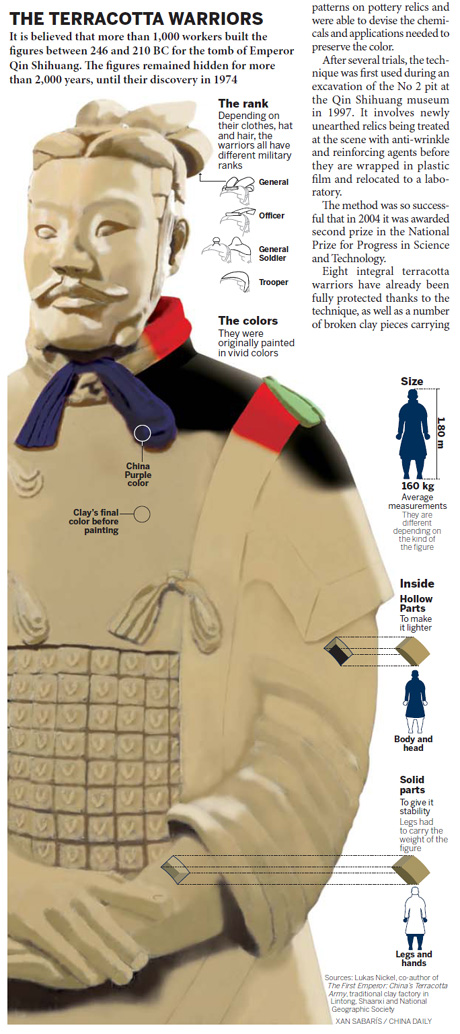

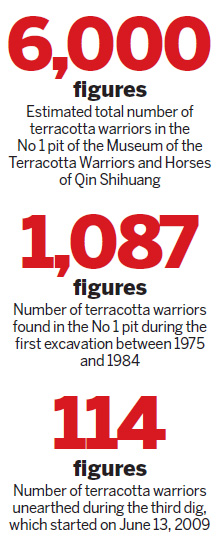

Along with the more than 114 broken figures unearthed since digging resumed in June last year, the discovery of three "suitcases" made of a silk-like fabric has offered clues on the textile industry during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

Arguably the starkest images to come from the dig, though, have been those of archaeologists dusting off the painted faces of newly discovered terracotta warriors.

"It was a pleasant surprise," said Xu Weihong, who is leading the excavation of the 200-square-meter-site, at the Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shihuang in Shaanxi province. "We found some painted in pink, red, white and lilac."

The colors better highlight the expression on the figures' faces and could prove invaluable to the study of ancient China.

And thanks to new technology developed in cooperation with a German institute, technicians on the scene were able to preserve the relics in their original painted colors - something that was unthinkable during the previous two digs.

The first, which lasted from 1978 until 1984, resulted in the discovery of 1,087 clay relics. However, after being exposed to air, they all quickly lost their color and turned an oxidized gray. (A second dig started in 1985 but halted a year later due to technical reasons.)

"When the excavation started, mold caused by moisture began to spread in the pits," said Wu Yongqi, director of the terracotta museum, which was officially opened on Oct 1, 1979. "When we wiped the mold off the surface dried out."

As the relics were cleaned on-site, experts found that the exposed paint would curl and fall off due to water loss.

Enter experts from Germany's Bavarian Administration of Cultural Heritage and Rome-Germanic Central Museum Mainz, who in 1989 joined forces with Shaanxi to research and develop new techniques to better protect the province's bounty of relics.

"One of the most important programs was the protection of newly unearthed terracotta figures," said Liu Yunhui, deputy director of Shaanxi cultural heritage bureau.

Susanne Greiff, head of the China-German heritage protection program at the Mainz museum, said the province was carefully chosen for the partner program for its wealth of history.

"Shaanxi is as large as the area of the former Federal Republic of Germany (prior to reunification in 1990) and its capital used to be the power center of 13 Chinese dynasties," she said. "Therefore, it has thousands of ancient tombs."

Despite the huge number of historic sites, at the time there was no modern relics restoration agency in the province or anywhere else in the country. The situation was critical, said Greiff.

Experts from both countries quickly set to work on establishing one, resulting in the Shaanxi Archaeological Institute's heritage protection and research laboratory in 1991.

Two decades later, many of the problems experienced in preserving and restoring ancient artifacts have been solved.

"In the last 15 years, I have been to Germany six times for training, staying there for three to six months each time," said Rong Bo, an archaeologist at the terracotta museum in Xi'an. "I learned a lot of things about heritage restoration and protection from our German colleagues."

Rong is among more than 100 specialists from Shaanxi who have received technical training in Germany, as well as in France, Italy, Japan and the United States. They have gone on to form the backbone of the province's heritage protection mission.

Work on preventing the terracotta warriors' paint from peeling began in earnest in 1990. Researchers examined the structure, distribution and patterns on pottery relics and were able to devise the chemicals and applications needed to preserve the color.

After several trials, the technique was first used during an excavation of the No 2 pit at the Qin Shihuang museum in 1997. It involves newly unearthed relics being treated at the scene with anti-wrinkle and reinforcing agents before they are wrapped in plastic film and relocated to a laboratory.

The method was so successful that in 2004 it was awarded second prize in the National Prize for Progress in Science and Technology.

Eight integral terracotta warriors have already been fully protected thanks to the technique, as well as a number of broken clay pieces carrying rich designs, said Ma Shengtao, deputy director of conservation and preservation at the Xi'an museum.

International cooperation in science for heritage protection has been credited with helping to raise China's overall technology level and making its excavation techniques and heritage protection the envy of the world.

"Our protective technology was poor and backwards before the Sino-German program," said Yang Junchang, general engineer and director of heritage protection and research at the Shaanxi Archaeological Institute.

The institute, which was established in 1958 and is the largest of its kind in the country, has excavated more than 10,000 ancient tombs. However, for a long time, protecting relics was a major concern.

"We unearthed some silk from a tomb once and the relics were completely destroyed minutes later as we had no proper way of dealing with them," said Yang.

With help from the Rome-Germanic Central Museum Mainz, which is renowned for its heritage restoration and protection, the institute built its own heritage protection and research laboratory (later renamed the protection and research department).

Today, the department has laboratories specializing in metal and ceramics, fresco restoration and textiles. It also has an archaeological site emergency team.

Past experience

For the last 20 years, Chinese and German experts have focused on relics from the Qin Dynasty and Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), with the first joint program the restoration of those taken for the underground palace at the Famen Temple.

Historians say the temple, which is about 120 kilometers from Xi'an in Fufeng county, was originally built in the 2nd century and was adorned with Buddha's bone during the Tang era.

The underground palace was only found in 1986 during a rebuilding project and many rare artifacts have since been recovered.

"The relics in the palace were placed in the underground palace before the year 1113 and many of them were damaged by the air and water that had leaked in," said Han Wei, former director of Shaanxi Archaeological Institute. "The major restoration for these damaged relics was done by German experts."

Sebastian Pechtold, who was on the German team, said more attention was paid to reproducing the original appearance of the relics rather than just making them visually beautiful.

"We couldn't just take Western methods and use them on Chinese relics," he said. "We had to consider the different materials and processes of manufacture before repairing the relics," said Greiff at the Mainz museum.

As the painting technology and processes of a mural found in a tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25-220) are far different from those used in ancient Rome and Egypt, so too are the techniques to restore them.

"We often met with new difficulties during our joint restorations," added Greiff, "which means we are constantly revising our plans, adding new programs and developing new tools."

One of the recent achievements of the China-Germany partnership is the restoration of a broken phoenix coronet, which belonged to Li Chui, a Tang princess who died in AD 736.

"The coronet was completely smashed when it was unearthed (in 2003), so we packed it in plaster and brought it back to the lab," said engineer Yang Junchang. "After careful preparation and research, about 10 Chinese and Germen experts worked for two years to repair it."

Materials used in the coronet were gold, silver, copper and iron, and it was also decorated with agate, pearls, amber, turquoise, glass and mother of pearl inlay. The surface was studded with gold beads that could only be seen clearly under a microscope.

"The coronet weighs 800 kilograms, is 42 centimeters tall and has exquisite workmanship," added Yang. "It is the only Tang Dynasty coronet that has ever been successfully repaired in the world."