Life and Leisure

Inspired by calligraphy, antiques and the Buddha

By Liu Jun (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-10 07:50

|

Large Medium Small |

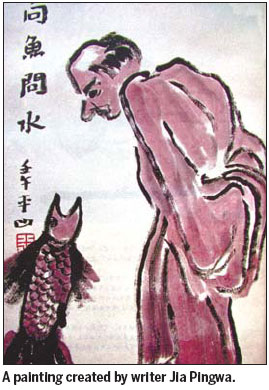

The two-story apartment where Jia Pingwa writes and meets guests is filled from floor to ceiling with hundreds of statues, pottery, wood carvings and strangely-shaped stones, besides the writer-cum-calligrapher/painter's own works.

"I don't collect them to make profits," Jia explains. "They help create an ambiance for my writing."

Like in his previous dwellings - be it a 6-square-meter kitchen in a publishing house's dormitory or a humble abode in a village for migrant farmers in the outskirts of Xi'an - Jia gives his study a grand title, Shang Shu Fang (Imperial Study).

"Thanks to my calligraphy and painting, I don't have to write about tomb raiders or eulogize entrepreneurs (the leitmotif of online writing)," jokes the chairman of the Shaanxi Writers' Association, acknowledging rumors that his calligraphy fetches the highest price in the local market: some 300,000 yuan ($44,200) for a 70 x 140 cm piece.

Jia is not the only one in Xi'an fascinated with painting and calligraphy. He says he knows of three groups of people copying his works at the city's Shuyuanmen antiques market.

"It's said some fakers earn more than 100,000 yuan a month with my works," he says.

The writer took to calligraphy in his childhood. Back in the early 1970s, Jia was working with fellow villagers to build a reservoir. Since he is short, he was not able to make as many "work points" as a woman.

Luckily for him, he excelled in calligraphy. So he was given another assignment, which was to carry a barrel of paint and a huge brush atop a mountain to paint Chairman Mao Zedong's clarion call for "Agriculture to learn from Dazhai!"

The bumper harvests in Dazhai village, located in Shanxi province, in the early 1960s was hailed as an example for the whole nation to follow.

Jia's exclamation mark alone was like a huge stick, say literary critics Li Xing and Sun Jianxi in their Reviews and Biography of Jia Pingwa.

The reservoir team's leader was so pleased with Jia's talent that he later recommended that he be sent to university, a move that changed the course of his life.

By the mid-1980s, many people were using his art works as gifts in business and official circles. "A lot of my works ended up in the nation's capital," Jia chuckles.

The money from his calligraphy came in handy to sustain his rather expensive hobby: collecting antiques.

"The antique dealers would swarm in. But for a 10 yuan piece of pottery or stone they brought, they would want my calligraphy or painting worth 50 yuan."

The self-taught expert in pottery and stone carvings says 80 percent of his collection comes from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220); some go even further back to the Warring States Period (475-221 BC).

In his apartment's kitchen sits a 1-meter tall black-glazed jar with a red cover.

"My wine is special, it's made of grains from the countryside, infused with ginseng, rare fungus and other precious herbs that my Buddhist and Taoist monk friends have found deep in the mountains," Jia explains.

The influence of religion is apparent in most of his works. While writing his latest novel, Jia found a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) bronze statuette of Sakyamuni, portrayed as a naked boy with one hand pointing up and one down.

"It means 'I'm the ONE between heaven and earth'," Jia says. "I put the statue on my desk and wrote the novel under his gaze. I believe he blessed my Gouniao Tai [a protagonist in the novel]," writes Jia in the epilogue of Ancient Kiln.

China Daily

(China Daily 09/10/2010 page19)