Life and Leisure

Digging deeper

By Liu Jun (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-10 07:50

|

Large Medium Small |

|

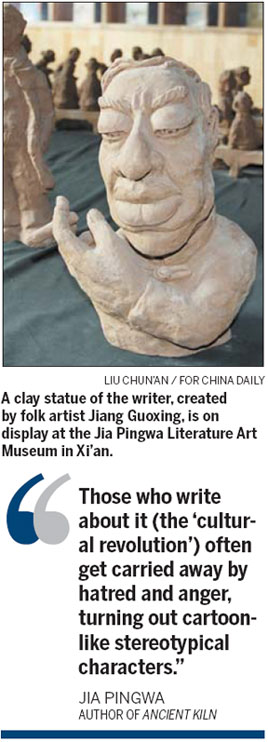

"It's only now that I finally know a thing or two about writing," says Jia Pingwa, one of the country's most prolific writers. Liu Chun'an / for China Daily |

Jia Pingwa's new novel, while set in the much-explored period of the 'cultural revolution', ponders the reasons for its rapid spread. Liu Jun reports

Horse bells clang when the door opens to the apartment in the heart of Xi'an, Shaanxi province. "Come in, make yourselves comfortable. I must wash my face - I'm still sleepy after my nap," says the short, balding host in a heavy Shaanxi accent. Jia Pingwa, one of China's most prolific writers, looks amiable and composed, a year after the ban on his Ruined Capital (1993) was finally lifted after 16 years.

Early next year, the writer's much anticipated novel Ancient Kiln (Gu Lu) will be published.

Jia says the novel, which took four years to complete, explores the reasons for the fire of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) spreading so quickly across the nation at the grassroots level.

It is set in a remote mountain village whose residents have been making porcelain for centuries. But their grinding poverty is fertile ground for igniting the kind of hatred the "cultural revolution" spawned. The book's six chapters mirror the six seasons from late 1965 to early 1967.

Asked why he places the novel in this much-explored period of Chinese history, Jia replies: "It's a mission I must complete."

Jia was in the first year of middle school when his teacher-father fell victim to the political turmoil of 1967. The teenager returned to his hometown, Lihua town, in southern Shaanxi's Shangluo city. Here he witnessed the upheavals, until hard work and good calligraphy earned him the chance to go to university in 1972.

On a trip back home recently, he says he saw two elderly men wading across a river, hand-in-hand. Thirty years ago, Jia recalled, caught in the madness of those times, they had been bitter foes.

Jia says many young people are ignorant about the 1966-76 decade.

"Those who write about it often get carried away by hatred and anger, turning out cartoon-like stereotypical characters," he says.

The "cultural revolution" led to the nation's social transformation. But Jia worries that everyone seems to be criticizing that period of history and no one is taking responsibility for anything. The term "cultural revolution" has become the culprit for all evils.

"It is only now that I finally know a thing or two about writing," says the 58-year-old writer.

Li Xing, a literary critic who has followed Jia's writing for 30 years, told Shaanxi Daily that Jia's new novel is the most profound work on the "cultural revolution" he has seen.

"He has faithfully presented the nation's shortcomings without vulgarizing anyone," Li says.

After Ruined Capital, Jia says he no longer pushes forward a story by plot, but instead plays narrator to the events of daily life.

Qinqiang (2005), which won him the much-coveted Mao Dun Literature Award in 2008, impressed readers with its exploration of multiple dimensions of rural life. Not just the fascinating human protagonists, even animals and plants are used to capture the pulse of village life.

Jia's upcoming work promises even more dimensions, portrayed through such unforgettable characters as the orphan Gouniao Tai, who shares his name with a poisonous mushroom on which, people believe, dogs like to pee.

Like Yinsheng the lunatic in Qinqiang, Gouniao Tai also communicates with animals and plants, living in a wonderland of his own despite his sufferings.

Jia's literary career has had an uneven course. His early works brought him great acclaim, until the landmark Ruined Capital turned him into a "villain", although this won him curious foreign readers.

The only one of his works not about farmers, the novel revolves around the hedonistic lives of scholar Zhuang Zhidie and his friends.

Despite the novel's eloquent narrative style, critics slammed it for its "decadent", "unhealthy", "end-of-the-millennium" feel.

Looking back at those times, Jia no longer feels indignant.

"Is the writer a dissident? No, he is a prophet who suffers bitterly and bears the brunt of criticisms. It is inherent in the nature of writing that there will be friction between the writer and the society he lives in."

Reacting to some comments that Ruined Capital was prescient about some of the fame-seeking scholars of today, the writer chuckles.

"Such people can be found at any time anywhere. What China needs is the 'public intellectual' - the one who will stand up to say what he feels about social problems.

"In this respect, many writers cannot compare with Han Han - he is young but he is outspoken. That's why he has so many fans from all age groups."

Jia is one of the few writers who has followed closely China's opening-up and reform and plans to return to his favorite theme, the Chinese countryside, after Ancient Kiln.

Talking of contemporary China, he says what worries him the most is the exodus of capable young farmers to urban areas.

Jia's next novel is likely to take on a rarely explored subject: the small counties.

In his trips to a dozen Shaanxi counties, Jia says he has observed that most have a big square and buildings lacking any aesthetic value. Life is laidback - people go shopping for fresh vegetables in the morning before going to work, use the free hot water on offer in the office for a wash, and go dancing on the square at dusk.

But this seemingly serene life masks a group of petty, self-aggrandizing officials who don't care two hoots for those projects that will benefit the farmers.

For nearly 20 years, Jia battled with hepatitis B, before making a miraculous recovery through, he claims, huge doses of vitamin C, among other medicines. But the writer, who smokes and drinks to his fill, is also quick to add the importance of maintaining a calm mind.

In fact, one of the characters in Ancient Kiln is an old doctor who tries to cure villagers by talking them into doing good deeds.

Jia will read the epilogue of his novel for a documentary featuring his hometown. The disc will be included in the book to be published by the Writers' Publishing House in January.

(China Daily 09/10/2010 page19)