Life and Leisure

Footprints on the sands of time

By Sun Li (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-14 08:03

|

Large Medium Small |

|

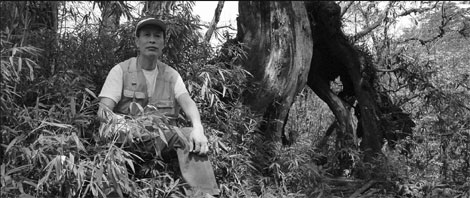

Over the past few decades, Yin Kaipu has devoted himself to cataloging the rich vegetation of Southwest China. Photos provided to China Daily |

Chengdu botanist travels the route taken by an English plant collector a century ago, to trace the ecological and geological changes that have occurred. Sun Li reports

Rare, wondrous plants draw many botanists to remote, perilous regions. But Yin Kaipu, a researcher with the Chengdu Institute of Biology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has braved earthquake aftershocks and other dangers on a different mission: following the footsteps of an English botanist to trace geological and ecological changes and their significance over the past 100 years in Southwest China.

Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930), a famous English plant collector, made four trips to the central and southwestern parts of China from 1899 to 1911 on a quest for rare plants.

Nicknamed "Chinese Wilson" for introducing some 4,700 plants from China to Western arboretums, Wilson also took a number of photographs during his expedition.

Over the past few decades, Yin has devoted himself to cataloging the rich vegetation in Hengduan Mountains bordering the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Sichuan Basin.

The 67-year-old Chengdu-based professor shifted his focus after noticing that many local plant species were named after Wilson - for example, the Regal Lily (Lilium regale Wilson).

He began to search for more about Wilson's excursions in China and came across a book titled Chinese Wilson. After seeing the photos of western China taken by Wilson a century ago, Yin says, "I got very emotional when I realized I'd been to many places in those old pictures".

But he also noticed that some of the scenes had changed dramatically. "I wanted to find the places and retake the pictures to study the environmental and social changes that had occurred."

From 2004 to 2007, Yin collected more than 1,000 photographs by Wilson from books, the website of the Herbarium of Harvard University, and overseas friends.

However, many of the old photographs were like scenery shots, offering little clue to their actual location. Many were named incorrectly or gave only general geographical explanations, which made pinpointing these locations extremely difficult.

After a five-year probe, Yin managed to decipher 250 pictures by 2009. He explored the deep mountains of Sichuan, visiting neighboring Hubei province and Chongqing municipality four times.

The major earthquake in Sichuan in May 2008 gave his project a fresh sense of urgency.

|

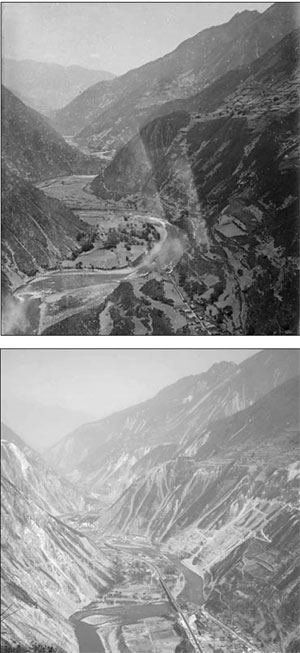

Two pictures showing the Minjiang River Valley in Wenchuan, Sichuan province. The picture above was taken by Ernest Henry Wilson in May, 1908. The other was taken by Yin Kaipu in March, 2009, showing the vegetation on both sides of the mountains ruined by the 2008 earthquake. |

"Wilson had been to some of the quake-stricken areas. I felt it was important to document the drastic changes the catastrophe had brought, despite the (risk of) aftershocks," Yin says.

To get a bird's eye view of Minjiang River Valley, just as Wilson had, Yin had to navigate labyrinthine mountain paths near Miansi town, Wenchuan county, the epicenter of the quake, until he found the vantage point, a narrow strip of flat land.

Another place he traveled to was the center of a dry riverbed, lying 50 meters below a highway. Yin crawled down steep slopes, dodging boulders and earthquake debris to reach the spot.

"It was worth it," says Yin, who also braved furious rainstorms, heavy snowfall and landslides in his quest.

The seemingly random, scattered images Wilson captured created a myriad of geographical and ecological coordinates that have helped later generations of botanists study and classify the native flora of the region. Yin's expedition added to these with valuable data.

Wilson once photographed a suspended bamboo bridge over the Jianjiang River, but the bridge, along with the hills behind it, were buried in the Tangjiashan Barrier Lake, formed during the 2008 earthquake in Xuanping township, Beichuan county.

He made other astonishing discoveries. Yin found that many river courses had changed; the ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Route from Yunnan and Sichuan provinces to the Tibet autonomous region had become wide highways, and some mountain slopes that were bare were now green, while dense forests in other areas had vanished.

Based on his studies, Yin concludes that while the ecology of some parts of southwestern China have improved marginally over the past century, it has deteriorated on the whole.

He recently published a book, Tracing One Hundred Years of Change: Illustrating the Environmental Changes in Western China, juxtaposing his photos with those taken by Wilson.

Yin has been invited to lecture ecologists, botanists, and experts in forestry, environmental science and mountain-disaster management about his findings.

"Nature is a mysterious book with infinite knowledge," the professor says. "The changes captured by the pictures hold a lesson.

"I hope 100 years later, there will be someone else who will follow Wilson's footsteps, and once again photograph the places he visited.

"That would make for another significant comparison."