Life and Leisure

Performance art is dead

By Zhu Linyong (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-15 07:53

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Dialogue and Demolition, an art piece many Beijingers are famimilar with, was created by Zhang Dali, in 1998. |

|

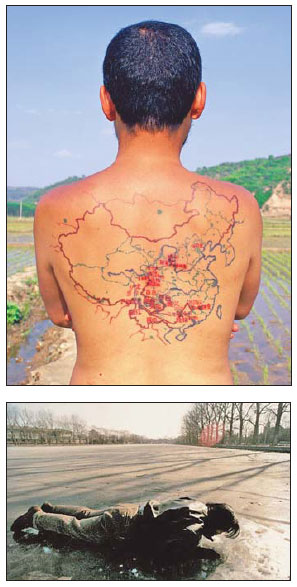

Above: In Miniature Long March, artist Qin Ga tattoos a record of his travels across China, following the Long March route. Below: Breathing, by Song Dong, involves breathing on the ground in different locations. |

It is no longer the provocative genre it once was now artists are succumbing to the pressures of commerce. Zhu Linyong reports

Peking University art professor Zhu Qingsheng recalls coming away disappointed from The Constructive Dimension, billed as "the first collective appearance of vanguard art in the new century", at the National Art Museum of China recently. "It failed to present a complete picture of Chinese contemporary art," Zhu says.

"Performance art, a crucial component of Chinese vanguard art, was absent from the much-hyped exhibition," he adds.

That missing piece can now be found at an ongoing exhibition at Pace Beijing, in the capital's 798 Art Zone.

Although featuring some of the most recognizable performance artists of today such as Zhang Huan, Song Dong, Yang Zhichao, and Qiu Zhijie, the exhibition's opening early this month was a low-key affair. There was nothing to suggest its title, The Great Performance.

Rather, it provides a history of performance art from the early 1990s to the present through the videos, installations, paintings and photographs of more than 30 of the most exciting artists of contemporary times, says curator Leng Lin.

Slated to run through Oct 16, it "offers viewers a chance to re-examine one of the nation's most shocking and provocative vanguard art genres" despite the absence of some of the more notorious, visually disturbing images, points out art critic Yang Shiyang.

Performance art first emerged in the West in the mid-20th century.

"It did not appear in China until the 1980s when the nation gradually opened its doors to the outside world and local artists began seeking more radical ways to express their yearning for freedom and independence," says art historian Lu Peng.

Breaking free of the long-dominant Socialist Realism style, this kind of art rose in prominence with the end of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and the start of China's reform and opening-up.

Its high season came in February 1989 when the first large-scale exhibition of contemporary art was held at the National Art Museum of China.

The exhibition ended abruptly in chaos after artist Xiao Lu fired two gunshots, as the final touch to her performance/installation work entitled Dialogue.

At the turn of the century, exposed to various art concepts from abroad and increasingly pressured by the fast-changing social reality to find new forms of expression, some Chinese artists began taking to performance art in a big way, Lu says.

In 1990, in Guangzhou, capital of southern China's Guangdong province, local artists including Xu Tan, Lin Yilin and Liang Juhui formed the Big Tail Elephant team, in response to rapid urban development, consumerism, traffic congestion and gender roles, in Southern China.

In one of their performances - Maneuvering across the Lin He Road - they built a brick wall on the side of a major thoroughfare in Hong Kong, then moved it brick by brick across the street, creating an enormous traffic jam.

The wall, they said, symbolized national and cultural borders; by moving it across the street, and creating urban chaos in the process, the artists said that it "showed the precarious situation in which nations find themselves when their political and economic borders shift".

It also showed, they said, resistance to the forces of the kind of modernization that the city of Hong Kong embodies.

Performance art became popular across the country in the 1990s, with artists staging numerous live shows in public spaces. Local media called them "strange and disturbing".

However, critic Huang Zhuan points out that the evolution of performance art in China has taken a totally different path from that in the West. Unlike in the West, performance art here comprises sporadic acts that are disconnected from the nations' art history.

"Chinese vanguard artists are taking advantage of every cultural and technological resource available - be it Chinese characters, ready-made objects, the human body, or videos, photographs, folk culture, and the Internet - to express their individual feelings and observations."

For instance, artist Xu Bing in his 1994 performance art - A Case Study of Transference - used Chinese characters and Latin words, ink, seals, pigs and boars, to express the idea of the collision of cultures.

Artist Song Dong sought inspiration from Chinese calligraphy, writing with a brush dipped in water to explore the philosophical idea of "creating something out of nothing." Zhao Bandi used a toy panda as a prop for his series of works on topics such as climate change, wildlife protection, and non-smoking.

Meanwhile, artist Zhang Huan tortured himself, attracting wide attention.

These works were referred to as shock art, provoking much debate about whether they could even be considered as art.

Consequently, some prominent performance artists, such as Ma Liuming and Cang Xin, have been barred from public exhibitions and shut out from media exposure on the mainland with their works being slammed as "shocking, disturbing and even subversive."

Not surprisingly, the performance art movement has lost its steam, says Leng Lin, curator of the on-going exhibition in the 798 Art Zone.

Some of the well-known names such as Zhang Huan, Xu Bing and Qiu Zhijie have taken to installations instead.

Zhang Huan admits that he has turned to ash paintings and cow-skin paintings "because of a lack of novel ideas and new inspiration."

Some say these artists are simply trying to figure out new ways of making more money.

While performance art is taboo at official exhibitions, "The surge of commercialism and consumerism and the advent of the Internet, have also demystified it as a sharp-edged, vanguard art", says critic Wu Hong.

"Performance art has become chic acts catering to the curiosity of the middle class and the newly rich."

The boundaries between art and life, and art and business, are also blurring, says critic Li Rongkun.

For instance, some netizens are assuming the role of performance artists, uploading their weird performances, in a bid for overnight stardom.

"Businesses are also hiring amateur actors and actresses to stage so called performance art," art critic Zhou Wenhan says.=

"The sole purpose is to draw more attention to their products ... whether there is art or not, nobody cares any more."