Life and Leisure

Cracking the red code

By D J Clark (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-23 08:18

|

Large Medium Small |

|

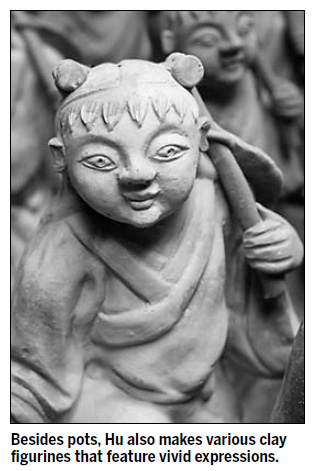

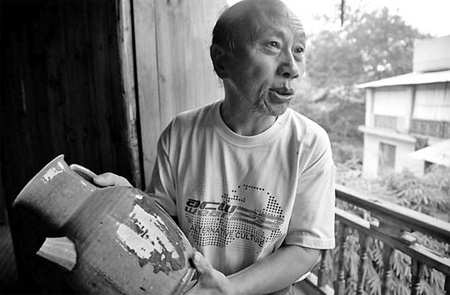

Hu Wuqiang follows ancient methods to make his ceramics, some of which have a rare red hue which makes them very popular among international collectors. Photos by D J Clark / China Daily |

In October 1999, 70,000 pieces of Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) porcelain were discovered. These were found inside a Chinese ship carrying merchandise that was wrecked off the coast of Indonesia more than 1,000 years ago. Around 60,000 of these antique pieces were made at Tongguan, a little-known town in Hunan province.

The discovery renewed interest in ancient pottery from Tongguan and gave a local potter new motivation to solve an ancient mystery.

Hu Wuqiang, 66, was born into a family of potters whose line could be traced back over 1,200 years. At school he became fascinated by a story about Tang Dynasty potters, who were said to use a special technique to color their pots red. The myth was well known in Tongguan, but no one could prove it.

Dressed in a stained shirt, Hu sits on a wooden stool in a room filled with drying clay miniature sculptures.

"There was a story about a copper red pot but no one knew how to make it," he recalls.

During his tenure in a ceramic factory, Hu became increasingly frustrated with the modern mechanical production methods. He quit his job and set about building a Tang Dynasty Dragon Kiln, shaped like the mythical animal.

"Our process is very simple because in the Tang Dynasty there were no machines," Hu explains. "All our products are created the traditional way, and all raw material is sourced locally. We don't need to do anything special. It's very simple."

One day, as he was scanning the site of an ancient kiln, Hu found the piece he had been looking for since he was a child - a fragment of a jar, with a red hue.

He studied it for several years and finally figured out how to attain the red color.

The secret lies in a unique combination of the local sand, copper oxidization, the glaze, and the unpredictable temperatures of the Dragon Kiln.

"The red comes from green," Hu smiles.

He continues to research and produce rare pots, which now fetch as much as 210,000 yuan ($31,000) a piece in auctions.

He plans to write a book to preserve the ancient secret for future generations of Tongguan potters and has enrolled several students in his small factory. His work is gaining a strong reputation in the international art world, though Hu admits that the kiln has a mind of its own and he has little control over the patterns that emerge.

"You can't control this Dragon Kiln. Every pot is different, which makes them all so desirable." Hu looks up and beams a confident smile, at having cracked the mystery. "I feel more and more interested in the process as it develops."

For China Daily