Life and Leisure

A stitch in time

By Liu Xin (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-23 08:18

|

Large Medium Small |

|

A Miao embroidery masterpiece can sometimes take three generations to complete. Photos by Qin Gang / for China Daily |

Authorities in Guizhou are making a concerted effort to save the delicate art of handcrafted Miao embroidery from losing out to its more-affordable machine-made counterpart. Liu Xin from China Features reports

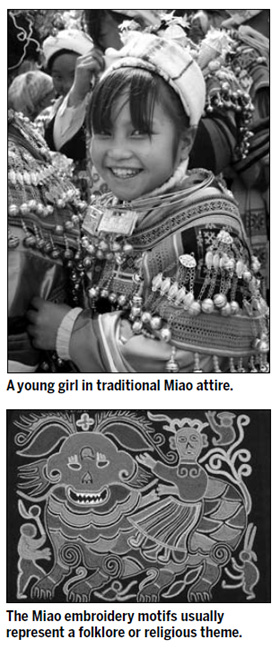

Wearing a black tunic with elaborate embroidery made by herself, Liu Ying of the Miao ethnic group is teaching her 11-year-old daughter to sew a dragon pattern in her 9-square meter rented house in south Beijing, as Miao folksongs play on a computer in the background.

"It's a shame in our culture if a girl cannot embroider," Liu says. "Miao mothers start teaching their daughters how to stitch when the children are about 5 years old."

The Miao embroidery motifs, like those of other Chinese ethnic groups, usually represent a folklore or religious theme. The motifs fall into three categories - geometric, landscape, as well as flower and animal patterns, and come in conspicuously bright green, red and yellow.

"The images are inspired by everyday life. The representation is abstract, imbued with great aesthetic value," says Wei Ronghui, deputy curator of the National Museum of China in Beijing.

A piece of fine embroidery reflects diligence and shows the family involved in making it is financially sound.

"You have to concentrate on stitching as your ancestors are watching you," Liu says.

A masterpiece - which sometimes can take three generations to complete - is worn only twice by a Miao woman, at her wedding and funeral. And then it will be passed down to the next generation.

"I have preserved the costumes my ancestors handed down," Liu says. "And my daughter will inherit these after my death."

Miao embroidery, which dates back to the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), was listed in 2006 as a national Intangible Cultural Heritage.

The 9-million-strong Miao are recognized as the fifth-largest of China's 56 ethnic groups. Most of them live in remote villages in Guizhou and Hunan provinces, and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region in southern China.

This ethnic style of needlework can be easily found in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, thanks to Miao traders like Liu Ying.

In 2000, Liu brought her handiwork to Beijing. "It took me a three-hour bus ride, and five hours or so on the train from my hometown Kaili city, Guizhou, to reach the capital."

She now travels the same route every month to purchase embroidery, mostly from workshops in Kaili, and sells them at her two booths in Panjiayuan - the largest antique and cultural items market in Beijing.

Machine-made garments sell at 300 yuan ($45) on an average, whereas hand-embroidered ones can cost over 85,000 yuan, depending on the level of craftsmanship and the time taken to finish the product. The price for regular items varies from 100 to 5,000 yuan.

Trading Miao embroidery has improved her quality of life, Liu says. "I can now make around 1,000 yuan per month on average after paying for my dorm and booth rental," she says.

Although this is not a large income by Beijing standards, Liu has been able to buy a new apartment in her hometown from her earnings.

Now there are around 20 stores and booths that retail Miao handicraft in Panjiayuan.

However, as the workshops producing machine embroidered pieces are doing well, the art of hand-made Miao embroidery seems to be on the decline.

Wei Ronghui noted that 80 to 90 percent of Miao needlework in the market is machine-made.

But, 20 years ago, when Miao embroidery first entered the markets, they were all handmade. Zeng Li, curator of Guizhou Ethnic Culture Museum, says: "At that time the embroidery would be done to meet traditional needs. But customers' needs have changed. Most of them prefer cheap ones to put up on the wall, for which machine-made embroidery is good enough."

She fears that the art of hand-made embroidery will soon be wiped out completely, given machine-made products cost much less.

A handmade piece taking more than three months to complete often sells for only 300-400 yuan, which is putting off a lot of the craftsmen from practicing this ancient and painstaking art, Wei explains.

Young girls no longer stay at home, but go out looking for employment in the Miao embroidery factories or in the big cities.

In Liu Ying's village, over 50 percent of her fellow villagers work away from home.

In fact, few Miao people selling ethnic embroidery in cities have any idea about their mythology - the history of the ethnic group's migration and evolution - that inspires the traditional patterns.

"The dragon doesn't represent 'royalty' as it would in Han culture. In Miao culture it stands for auspiciousness," Zeng Li says.

Any pattern or symbol on clothes, Zeng points out, is meant to convey a message, "as Miao people have no written language". All the more reason why Miao symbols and embroidery must be preserved, she adds.

Local authorities have now introduced a series of projects to help keep this ancient artistic heritage alive.

A digital museum showcasing thousands of Miao embroidered artworks will open in 2011 in Guizhou. A database featuring the history, features and artistic value of Miao embroidery is now on public view.

Yang Xiaohui, the database's project director from the provincial culture and art research institute, began working on the project in 2008. He traveled around the eight provinces where the Miao mainly live, collecting information. "At least we would still have some literature and files on Miao embroidery, should it die out," Yang says.

Meanwhile, some schools in Guizhou provide incentives to students to learn about Miao embroidery.

"Many Miao mothers have gone to work in cities, leaving their daughters at home with virtually no one to teach them the art of stitching," says Wei Ronghui. "Hopefully, the schools can equip these children with some basic skills of Miao embroidery."