Focus

Bountiful land faces barren future

By Li Jing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-09-28 08:02

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Farmer Hu Jinghe cherishes the highly productive black soil of Binxian county, Heilongjiang province, as he awaits a bumper corn harvest in this fi le photo taken in September. [Photo by Feng Yongbin/China Daily] |

|

Cui Xuefu grazes his cattle in a cornfield near an erosion gully about 50 meters long in Binxian county, Heilongjiang province. Northeast China has long been famous for its rich black soil. [Photos by Feng Yongbin/China Daily] |

|

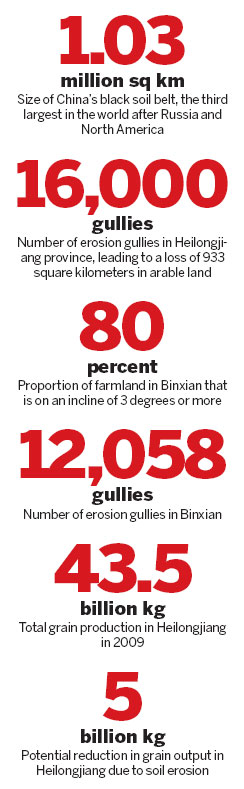

Yin Jiafeng, a researcher with Heilongjiang's Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute, shows the areas worst affected by soil erosion on a map. |

|

A farmer holds a handful of black soil. |

Erosion of nutrient-rich black soil threatens China's grain production. Li Jing reports from Heilongjiang.

Farmer Hu Jinghe has high hopes for his harvest this week. After a year of moderate temperatures and timely rainfall, his cornfields are now a lush forest of green stalks.

"It's the black soil," said the 62-year-old in Binxian county, Heilongjiang province. "It provides really good conditions for growing crops."

For many like Hu, black soil - or chernozem, as it is also known - is a gift of nature. Formed in cool, temperate zones with meadow-grassland vegetation, farmers say the soil is so rich in nutritional properties "you could even grow chopsticks in it".

Yet, Hu fears such good harvests will disappear in the coming decades as the once-bountiful land continues to lose its luster.

Official monitoring data shows rainfall is washing away up to 10 millimeters of black soil every year in some areas, while in others, layers are already down to about 40 centimeters, half the depth recorded at the start of agricultural reclamation in the 1950s. If such erosion continues, black soil could vanish within the next 50 years.

The worrying trend has alarmed experts nationwide, not least because black soil farms - mostly in the northeast provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning - produce about one-sixth of China's grain, even though the long, harsh winters prevent farmers from harvesting more than once a year.

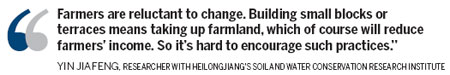

Covering an area of 1.03 million square kilometers, the black soil belt is the third largest in the world after Russia and North America.

Beside Erlong Mountain in Binxian county, 57-year-old Cui Xuefu grazes his cattle in a cornfield near an erosion gully more than 50 meters long.

Despite several check dams - small stone barriers placed on slopes - have been built in the huge crack to slow down the erosion, the crevice is already more than 1 meter wide and about 2 meters deep and expands every time there is heavy rain.

"It used to be farmland, just like the surrounding cornfields" said Cui. "The gully started as just a small crease on the hillside about two decades ago but has gradually grown as rain has flushed away the surface layer of earth."

More than 16,000 erosion gullies have opened up around Heilongjiang, leading to a loss of 933 square kilometers in arable land, according to the province's Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute.

Binxian county, where more than 80 percent of farmland is on an incline of 3 degrees or more, is one of the areas worst affected. About 75 percent of its 3,860-square-kilometer territory suffers soil erosion, with 12,058 gullies already reported by the county's water conservation office.

As irrigation here is still very much dependent on rainfall, farmers make ridges along slopes to use rainwater to irrigate their crops. However, this practice inadvertently removes the topsoil.

Experts say that the unique land structure in the black soil region means once the top layer is gone, the ground is no longer suitable for cultivating crops.

"We've seen a dramatic loss of arable land (because of this)," said Zhang Runru, director of water conservation for Binxian county's water bureau. "It's a serious problem we're facing."

Black soil gradually accumulates over hundreds of years as a result of slowly decaying organic matter. Yet, below that is usually stiff and sticky yellow earth that is impossible for plants, especially crops, to take root in.

Fertilizer frenzy

Close to the gully where Cui grazes his cattle is a small patch of land already so barren that it cannot be farmed anymore. A smattering of cornstalks covers the area, which is now largely sand and rocks.

"All the money and effort we were putting in - furrowing the land, sowing, paying for chemical fertilizer and labor - we weren't getting back from the production," said Cui. "So we just stopped working on it."

Researchers discovered that when the thickness of black soil is reduced to about 20 or 30 cm (the average depth is 50 cm), the content of organic matter in the soil falls 30 to 50 percent.

About 15 kilograms of nitrogen and phosphorus and about 28 kg of potassium- essential ingredients for growing crops - are lost from each mu (a Chinese measurement equivalent to 0.06 hectare) of farmland every year due to soil erosion.

As a result, annual grain production is potentially reduced by 25 to 40 kg per mu.

Cui said that, when he was young, the natural fertility of the land in Northeast China was strong enough to support the crops. During the past two decades, though, there has been an increasing reliance on chemical fertilizers.

Despite warnings from experts that the overuse of chemicals worsens the degradation of black soils, the farmer admitted he and the fellow villagers had recently "doubled the use of chemical fertilizers to 50 kg per mu".

In the old days, households would compost animal manure and wasted stalks, which restored some of the soils nutrition. "But after the introduction of mechanized farming and chemical fertilizers, farmers became reluctant to spend as much effort as before," said Zhang in the water conservation office. "It's really a pity."

Reversing the trend

Total grain production in Heilongjiang hit 43.5 billion kg last year, contributing to a national output of 530.8 billion kg, according to figures from the National Development and Reform Commission, the country's economic planning body.

However, studies by the Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute show the loss of farmland due to soil erosion could cost Heilongjiang 5 billion kg in grain output.

To prevent the potential threat to China's food security, authorities are throwing millions of yuan to relieve the soil and water erosion in the black soil region.

Zhang, who has been in the field for more than 20 years and works with farming communities on conservation projects on a daily basis, knows every gully in Binxian county. He said that building check dams in cracks has proved an effective way to prevent them from expanding further.

"The soil flushed down (by the rainwater) accumulates on the dams, which gradually fills the cracks," he explained. "This method is especially useful for small gullies."

Check dams have been built in more than 4,600 gullies across Binxian county, with work still ongoing. Each project is expected to cost about 10,000 yuan ($1,490).

"The central government provides an annual fund of 4.8 million yuan for water and soil erosion conservation, along with a 1.92-million-yuan investment from the provincial authorities and 480,000 yuan from the county," said Zhang.

Unfortunately, there is no quick fix for soil erosion. For slopes less than 5 degrees, research suggests changing direction of the ridges carved by farmers so that furrows can hold rainwater. Constructing terraces or small blocks in the ridges on inclines of between 6 and 15 degrees can also help prevent black soil loss.

When experts attempt to persuade farmers to employ these tactics, however, they often meet with strong resistance.

"Farmers are reluctant to change," said Yin Jiafeng, a researcher with Heilongjiang's Soil and Water Conservation Research Institute. "Building small blocks or terraces means taking up farmland, which of course will reduce farmers' income. So it's hard to encourage such practices."

The county government has also urged villagers to stop farming on hillsides steeper than 15 degrees and instead plant trees.

"Reducing agricultural activities can prevent soil erosion, while trees can better conserve the land," added Zhang.

Farmer Hu Jinghe said he stopped cultivating crops on about one-third of his 60 mu of farmland in Pingyi village several years ago.

According to the central government's policy on returning land from farming to forestry, Hu can get an annual subsidy of 160 yuan per mu for eight years. After that, the subsidy drops to 90 yuan per mu for another eight years.

As the policy cannot cover all the households in Binxian county, though, Zhang said it has become more difficult to persuade villagers to stop farming.

"All I can give them is free saplings, not compensation," he added.