Life and Leisure

A miner's diary

By Lan Tian and Sun Ruisheng (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-08 08:04

|

Large Medium Small |

|

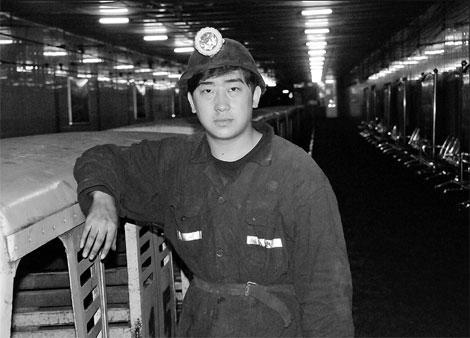

Wang Gang, 24, has followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather to become a miner in Huairen, a county with dozens of coal mines in coal-rich Shanxi province. Yin Zhiyong / for China Daily |

Despite increasing mechanization, life in the cold, dank, dark interiors of a coal mine remains as tough as ever. Lan Tian and Sun Ruisheng report

Growing up in the rural coal-mining community of Northern Shanxi province, Wang Gang knew just how tough and risky a miner's life can be. And he swore to himself that he would never follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather.

But destiny had other plans.

Wang, 24, eventually returned to the community he once spurned, despite graduating from Shanxi Drama Vocational College in the provincial capital, Taiyuan.

"Given a choice, I would never work in a mine," says Wang dressed in a pair of old jeans, white tennis shoes and a brown artificial leather jacket, dirt clogging his long fingernails.

He has traveled a long way from the halcyon days of 2002, when the drama college student, a fan of Guns N' Roses, formed a four-member rock band, BY.

After class, the band would do the rounds of the nightclubs of Taiyuan, with Wang its lead singer/guitarist.

But BY did not get progress past being a warm-up band and soon broke up.

Wang then worked as a DJ, and sound and lighting engineer in bars, where he fell in love with a dancer, Zhang Yue.

When Zhang became pregnant, Wang asked her to marry him. Their daughter was born soon after.

He was making a modest 5,000 yuan ($740) a month at that time, which was just enough to get by.

But Wang felt working at nightclubs was full of temptations, and not conducive to a stable family life. So, despite the prospects of becoming a partner at the bar where he had worked for years, he quit.

"I like rock music, but I'm also a very conservative man," Wang says.

The couple soon spent all their savings as he could not find another job with a salary decent enough to pay for baby milk and diapers.

Wang returned to his hometown, Huairen, a county dotted with dozens of coal mines like countless others in the coal-rich province.

In March 2009, he began life as a miner in Wangping Mine Company, a State-owned mine where his father had once worked.

He clearly remembers how frightened he felt the first time he went down the maze of mine tunnels.

"It felt like hell," Wang says.

Typically, a miner works 21 shifts every month to make the maximum he can - 4,000 yuan. Each shift lasts 12 hours and starts at 5 am, 1 pm and 9 pm.

Wang works the 1 pm shift. After a pre-shift meeting and an oath ceremony where the 10-member squad of miners vow to ensure safety, he changes into his work overalls.

Carrying his gear and equipment weighing some 100 kg, he boards a mini-train to descend the mine.

The train comes to a halt half an hour later. He gets off and walks another 20 minutes before reaching his work area.

There is darkness everywhere.

Besides the miners' headlights, there is just one light for every 100 meters along the tunnel.

The ground is cold and moist, with the chill factor amplified by ventilation fans used to blow fresh air into the mine, and the sprinkler that keep the coal dust down.

Wang has to wear three layers of cotton-padded clothes and trousers to protect himself from the cold and dampness.

In the past, miners used picks and shovels to dig the coal and load them on to small carts. Then mules would pull the carts to the entrance.

Nowadays, with mechanization, machines are replacing miners to dig the coal.

But Wang, a newbie, is unfamiliar with these machines. His main tasks are to assist senior miners, carry equipment and prop up the mine roof with support materials.

His shift ends at 10:30 pm, by which time his clothes are soaked in sweat and his face covered with black dust.

Taking the same mini-train back to the entrance, he cleans up in the miners' bathroom, and arrives home around midnight.

His wife always stays up until he gets home safe and sound.

All the miners' families are aware of the risks the miners face and live with them. In compensation, they enjoy the highest monthly salaries in the area, which is almost equivalent to the annual income of local farmers.

As the world's largest producer and consumer of coal, the country's annual output of coal tripled from 1 billion tons in 1999 to 3 billion tons in 2009, to fuel the fast-growing economy.

Its coal mining industry remains one of the world's deadliest, although the situation has been improving, with the mortality rate per million tons declining from 5.71 in 2000 to 0.892 in 2009.

Accidents killed 2,631 coal miners in 2009. That was down from 6,995 deaths in 2002, the most dangerous year on record.

Having worked underground for 18 months, Wang says the worst thing about being a miner is not the danger but the "darkness".

In the winter, he often goes without seeing the sun for weeks, if the shift starts at 5 am and ends at 5 pm.

"Mechanization and stricter supervision have greatly improved mine safety.

"As long as you pay 120 percent attention and follow safety instructions, you will be OK," he says.

Although Wangping, a medium-scale mine with an annual production of 1.5 million tons, has not seen a severe accident in years, Wang says this does not mean no blood has been shed.

Failure to follow instructions can result in ghastly wounds such as multiple compound fractures.

Wang recalls the utter shock he felt when he chanced upon several fingers of a young co-worker, which were accidentally severed.

Wang's experiences have transformed him, body and mind.

While the day-to-day physical work has bulked him up, he also suffers from joint pains and a cough, owing to the cold, damp and dusty environment underground.

"It is one of the hardest, dirtiest and most dangerous professions in the world," Wang says.

While miners are often thought of as victims of disasters, he is at pains to point out that "we miners are very brave, industrious, are able to work under great pressure, and pay constant attention to detail".

And it is a man's world - State labor laws prohibit the employment of women to work underground.

During breaks and meal times, the hottest topic is women. Who is the best looking girl in the community? Or, who is cheating on whom?

"It is the only entertainment we have underground," Wang says.

The trading of profanities and crude insults is common, and helps ease the stress of mine work, he says.

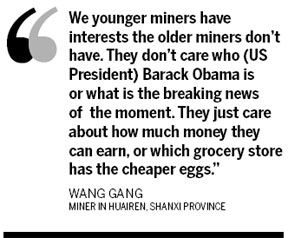

But as a post-80s college graduate, Wang senses a distance between him and older miners.

Of the mine's 6,000 employees, about 1,000 are miners, of which 30 percent belong to the post-80s generation, holding at least a senior high school diploma.

Most of the older miners have just a primary school education and some are illiterate. The oldest miner in Wang's team is 44.

"We younger miners have interests the older miners don't have. They don't care who (US President) Barack Obama is or what is the breaking news of the moment. They just care about how much money they can earn, or which grocery store has the cheaper eggs."

Few of the educated older miners surf the Internet, while Wang spends almost all his spare time online, teaching himself computer programming.

"Mining has isolated them from the outside world, and made them numb."

Wang says he has to constantly remind himself not to succumb to such numbness.

"It is just a job. I won't dig coal forever. I still have dreams," Wang says.

He says he will leave the mine if there are better job opportunities. Older miners tell him he's being impractical, but his family supports him.

For the time being, Wang is focused on a singing contest his company is organizing.

He will sing his favorite song - Chinese singer Wang Feng's Life in Full Blossom:

I have lost my dreams many times;

I want to go beyond the common life;

I want life in full blossom;

Just like flying in the vast sky.

(China Daily 10/08/2010 page20)