Life and Leisure

Monkey king

By Li Xing (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-14 07:57

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Chongzuo Biodiversity Research Institute is nestled in the mountains of southwestern Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Photos by Huo Yan / China Daily |

|

A family of langurs, which are polygamous. provided to china daily |

|

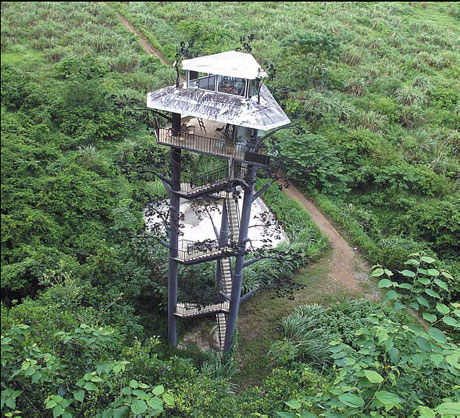

A 33-meter-tall iron tower houses close-circuit cameras to record the langurs' activities. |

White-headed langurs are native to China and researchers say they share quite a few traits with the feudal families of ancient times. Li Xing reports

I can feel multiple pairs of eyes staring at us as my colleagues and I crouch in a stone cave in a big karst hill in Nongguan mountains, in the southwestern part of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Before we mount a wooden platform, we feel the morning dew dropping off the leaves on our skin.

"Move, it could be langur urine," Lu Jintong, 40, a handyman at the Chongzuo Biodiversity Research Institute, whispers.

Despite Lu's warning, I raise my head to see who is watching and making fun of us up on the cliff. The movements in the trees overhead stop. In the bright morning rays, I catch sight of a couple of monkeys with tails longer than their bodies, hanging down.

Although I cannot see their almost pitch-black faces clearly, I easily spot them from their head of bleach-white hairs, shaped like a witch's hat. Their newborn babies, however, have golden hair.

As I survey the cliff, I see several other langurs climb nimbly, holding on to the crevasses. A few mothers carry their babies and move with the same agility but with considerable care.

Some 15 minutes after we arrive at the vantage point, all the langurs disappear from the cliff, the trees and our sight.

They will spend the whole day feeding on more than 100 plant and flower species and at high noon, they will take shelter in the forests and help each other comb their hair, Qin Dagong, deputy director of the Chongzuo institute, tells me.

However, a few pairs of eyes are still watching us, through three high-resolution close-circuit television cameras, with their monitor installed about 1,500 meters away in the research institute's head office.

One of those pairs of eyes belong to Professor Pan Wenshi, China's foremost giant panda expert, who founded the institute. He has studied the white-headed langurs for 14 years in Chongzuo.

Indigenous to China, the white-headed langurs are a critically endangered species that are on the list of Nature Conservancy International. With their ancestry dating back some 3 million years, they seem to have lived only in the southwestern part of today's Guangxi.

Although their 24-hour monitoring under close-circuit cameras began only a year ago, researchers have already documented a large langur family of 31 members for years.

On Jan 13, the researchers spotted a young pregnant mother fidgeting on the cliff. "I immediately sensed that she was going into labor," Pan Yue, Professor Pan's younger daughter and a businesswoman, recalls.

The team had, of course, seen langur mothers giving birth before. "I've seen one pulling out her baby in the open," says Lu, who joined Pan's research team four years ago.

However, after a baby is born, other females surround the newborn, taking turns to hug or carry the baby.

"But we went beyond being just an eyewitness this time. For the first time, we documented in full how a young mother goes through hours of labor pains and finally gives birth," Pan Yue, who has joined her father's research as a volunteer, says excitedly.

Research on wildlife takes years to bear fruit, Pan Wenshi says, showing the family tree he and his students have compiled through their daily observations of one langur group for 14 years.

The langurs are polygamous. The researchers liken them to the big feudal families of ancient China, with a patriarch, his wife and concubines as well as their children.

The family that has been under the closest watch by Pan and his students since 1996 has seen its patriarch change four times.

It is now headed by a middle-aged male nicknamed Yintang Xiaotu, or Little Patch of Baldness on the Forehead.

Little Patch's reign began in the middle of 2006. Like three of his predecessors, he has to give up his "throne" after he grows older and can no longer protect his big family.

He can expect a younger but stronger male from the outside to invade his turf, fight him and drive him away. The power change is brutal, as the new patriarch takes control of the fertile females and tries to kill their infants so that he can have his own children.

Although Little Patch will accept defeat, he will not abandon his children. Instead, he will take them along and raise them with the help of his older sons.

In January 1998, Pan and his students heard a male langur called Tutu letting out a single syllable, ai. In more than three hours, they recorded 735 ai from Tutu.

"We guess the male head of a family was marking out his turf, warning other families not to intrude," Pan says.

The karst hill where we had a close encounter with the langurs is Little Patch's family home. It once served as a military warehouse. The cliff above the former warehouse with its small caves, buttresses and crevasses, is the family bedroom.

The previous evening at dusk, we watched the family return to their beds after a day's "work", from a 33-meter-tall iron tower, standing some 40 meters from the cliff. Erected early last year with donations from Wang Shi, one of the nation's real estate tycoons, the tower also houses the close-circuit cameras.

In twos, three and fours, the Little Patch family made their way adroitly down the sharp cliff. Mothers held their babies tight while the older ones lent a helping hand to the younger, fearful ones. They then settled down for a well-deserved rest.

But their night's sleep was not without interruptions, as they needed to answer calls of nature.

Pan had plastic buckets lined up on the wooden platform under their "beds", to collect their droppings.

"I didn't know their droppings were so precious," Lu says, as he carefully places his "collection" into the buckets.

Pan tells me his team will take their studies to a new and molecular level.

"The droppings and hairs will help us learn how these leaf-eating monkeys passed down their DNA and their genetic traits and evolved over the past 3 million years," he says, beaming.

|

Handyman Lu Jintong checks the plastic buckets lined up to collect langurs' droppings. |