Life and Leisure

Journey of discovery

By Liu Jun (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-15 08:19

|

Large Medium Small |

|

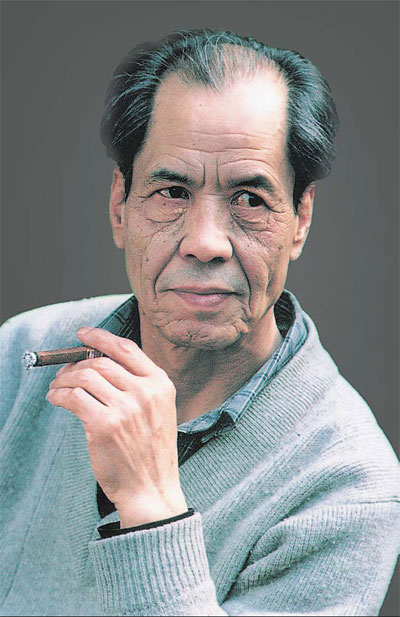

Chen Zhongshi is known as the "old farmer" in literary circles. Photos provided to China Daily |

Chen Zhongshi's novel examines the moral dilemmas that confront people caught in the midst of major upheavals, and draws richly from his own life. Liu Jun reports

In 1991, when Chen Zhongshi was about to wrap up his magnum opus that had taken him nearly four exhausting years to write, he joked with his wife that he would start a chicken farm if the novel failed. After all, a stewed chicken-with-mushroom dish can easily earn 100 yuan ($15). Fortunately for readers, the novel, White Deer Plain (Bai Lu Yuan), turned out to be a huge success.

It has been unanimously hailed by critics as a must-read for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the country.

A tall, lanky man with graying hair arrives at exactly the appointed time at a restaurant in Xi'an, capital of Shaanxi province, one August evening. The firm and warm handshake belies the deep wrinkles on the face of the 68-year-old.

Chen has been called the "old farmer" in literary circles, but his solemn air reminds one more of Master Zhu, the countryside scholar and spiritual leader of his novel.

Last year, he published In Search of My Own Sentences - Notes on Writing White Deer Plain, which sheds light on the source of his inspiration. Chen also reveals the parallel journeys of discovery taken by him and the characters in his novel.

"What makes the Chinese different from Westerners is not black or blue eyes, or black or blond hair," Chen says in a slow, heavy dialect, puffing on a thick cigar.

"Since childhood, a Chinese is steeped in values of good and evil, which mold his psychological make-up and guide his actions under different circumstances.

"Any threat to them plunge him into deep pain as he struggles between upholding and abandoning old values, before finding a new balance."

Chen deliberately places his characters, mostly farmers in the Bai and Lu families, amid the social upheavals of the 1910s to 1940s - the downfall of Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) up to the dawn of New China.

While Master Zhu tries in vain to hold on to the old values with the support of his brother-in-law and clan chief Bai Jiaxuan, the younger generation eagerly embraces fresh ideas - some join the Communist Party, others go over to the Kuomintang, a few become opportunists seeking personal gain.

Chen resorts to few descriptions or dialogue, yet is able to make his characters sound authentic, as he draws generously from personal experience.

He was a rural teacher and commune cadre for some 20 years before becoming a professional writer in 1982. As China opened up and reformed, Chen felt everything he held dear being challenged.

Since middle school, this son of an ordinary farmer had worshiped Liu Qing (1916-78), a veteran writer who showered wholesome praise on the dramatic changes in the countryside in the 1950s, in his History of Creation (Chuangye Shi, 1959).

Chen believed that the commune system had served farmers well. But in 1982, he was assigned to distribute land to farmers, signaling the end of this system. The author's doubts find expression in the novella On the Morning with Bright Sunlight (Xiaguang Canlan de Zaochen, 1982), in which an old farmer who has been taking care of the commune's cattle leaves with a heavy heart after farmers take the oxen home.

But his doubts melted away that autumn, when farmers celebrated a bumper harvest not seen in years. From his small plot of land, Chen and his wife filled 20 bags with some 1,000 kg of wheat, which he says could sustain his family for two years.

More changes were to come.

In 1985, during a trip to Thailand with other writers, Chen was surprised to see in a Bangkok supermarket that no two customers were dressed the same. At that time, for decades, Chinese had been clothing themselves in black, blue and army green.

That left such a strong impression on him that Chen wrote Master Blue Robe (Lanpao Xiansheng, 1985) about a man born in a rural teacher's family. The solemn blue robe he wore symbolized that family's high status among farmers. But the young man takes it off after attending a new school and being exposed to its liberating thoughts.

As the nation opened up further to the outside world, and a flood of new ideas rushed in, Chen and other writers were forced to reassess their own writing.

"The depth of a writer's work is limited by the depth of his understanding of life," says Chen, who fondly recounts works by Anton Chekhov, Maxim Gorky and Guy de Maupassant.

But it was Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier and Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez who boosted his confidence to write about his homeland in his own language.

"Latin American authors taught me how to face the history of one's own nation. That's when I realized how shallow my understanding was of my own land," Chen recalls.

His journey of discovery was full of surprises, sadness and joy.

As he thumbed through flimsy, yellowing pages of four counties' annals, he found volumes of the so-called zhenfu lienu (chaste women). Shackled by feudal customs, these ancient "role models" remained faithful to their deceased husbands, earning empty recognition in exchange for their miserable lives.

A bold idea struck Chen: Why not depict a woman who follows her instincts instead of staying a walking corpse? That led to the birth of Tian Xiao'e, the memorable and tragic heroine of his novel.

Having lived among farmers for decades, Chen offers great insight into the Chinese countryside.

The huge rural population makes it impossible for farmers to earn a decent living off their small plots of land.

But only the most capable can make it in the city. Pastoral life and the rich, age-old folk customs associated with it are bound to decline.

A nation's hope, Chen says, lies in the ability to assimilate the essence of ancient wisdom while adapting to the changing times.

The novel's Master Zhu is based on Niu Zhaolian, a legendary scholar in Chen's hometown. Chen grew up listening to tales about Niu, like how he persuaded a ferocious warlord not to destroy Xi'an in the 1920s, and led other silver-haired scholars to fight the Japanese on the frontline in the 1940s.

Niu was the last of the Guanzhong School of scholars started by Zhang Zai (1020-78), whose famous saying that all scholars should "form the soul of heaven and earth, save the masses, carry on ancient saints' thoughts, and establish peace for future generations" was once quoted by Premier Wen Jiabao.

"Zhang Zai's saying is the cream of our nation and it should be passed on," Chen says.

At the end of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), Chen was nearly 50. Like other writers, he had not been able to write anything freely.

"I just wrote the novel (White Deer Plain) out of a pressing need to leave something behind when I die. Then I won't have any regrets," Chen says.

The novel's French translation is expected in 2011.

|

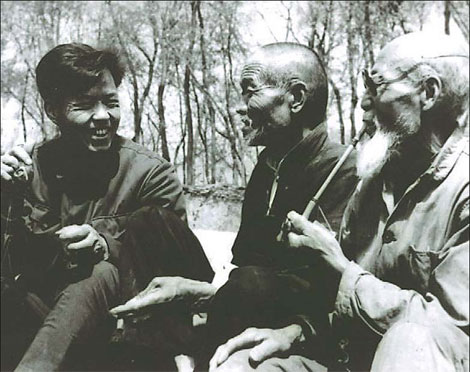

Chen Zhongshi (left) lived and worked in rural areas for 20 years, which inspired his writing. |