Life and Leisure

Crafting a revival

By Guo Shuhan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-19 07:56

|

Large Medium Small |

|

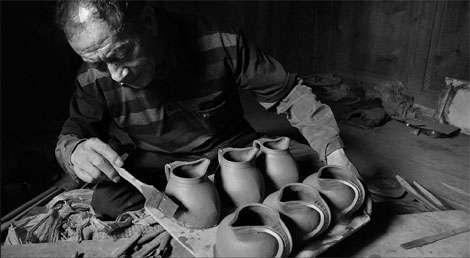

Sunnuo Qilin makes teapots of black pottery in Tangdui village, Diqing Tibet autonomous prefecture, Yunnan province. Photos by Wang Wei with tengxun / for China Daily |

Sunnuo Qilin is a black pottery master who is trying to update the traditional craft in an effort to keep it alive. Guo Shuhan reports

Sitting cross-legged on the floor, Sunnuo Qilin meticulously adds a handle to a just-shaped container for buttered tea. He then polishes the body of the pot with a piece of wet deerskin, and pinches a pattern on the handle.

Sunnuo is applying the finishing touches to a black pottery piece, a product in Tangdui village, Nixi township, 39 km from Shangri-La county, Diqing Tibet autonomous prefecture of Yunnan province in Southwest China.

The pottery gets its name from the fact that after firing the clay in the open-air, the earthenware is immediately put into a mixture of sawdust and charcoal, which turns the surface black.

Sunnuo, a State-level pottery producer, has been making black pottery for more than half a century.

The 62-year-old is used to sitting from 8 am to 5 pm doing the centuries-old handicraft with a variety of self-made wooden tools. Cold weather in the high altitude makes a blanket essential to keep his legs warm.

Despite his age, Sunnuo can still make 20 teapots a day.

"For me, black pottery represents traditional Tibetan culture in Diqing Tibet autonomous prefecture," says Sunnuo, who is a seventh-generation potter and currently the most revered black pottery master in the village.

Located on the Ancient Tea and Horse Route, a narrow and dangerous commercial route used to ship tea and sugar from Yunnan and Sichuan provinces to Tibet in exchange for horses and salt, Tangdui village has a tradition of making black pottery stretching back more than 1,000 years.

Twice a year, between March and May and also November and January, when the weather is dry, craftsmen from the village collect the red clay from a mountain some 6 km away, and stockpile it.

Currently, 89 of the 147 households in the village are producing pottery using the skills they learned from Sunnuo.

It takes at least seven years for one to master the basic skills necessary to produce the black pottery, Sunnuo says.

The craft was almost entirely lost during the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976).

Sunnuo, however, still made simple daily necessities, in secret, for people in Tangdui or neighboring villages.

Then, in 1975 the Nixi government decided to build a pottery plant. Sunnuo and two other masters in their 60s, were invited to be the instructors.

During the 1980s, villagers still shouldered or transported products by horse to sell in Shangri-La county, this usually resulted in around one third of the pottery being broken on the way, Sunnuo says.

With tourism booming in Shangri-La in the 1990s, the reputation of black pottery began to grow. Besides domestic buyers, orders also started coming in from foreign countries like the United States, Japan, Switzerland and India.

The annual income per person increased and it is now around some 5,000 yuan ($747.5) on average, nearly 10 times the amount before the village's black pottery was known to the outside world.

The village currently produces about 110 different black pottery items, encompassing daily necessities like teapots and boilers, religious pieces like incense burners and butter lamps and handicraft items like ashtrays and vases.

Based on the suggestions of tourists and buyers, the decorative patterns are now more diversified and complicated.

Sunnuo's second son, Larong Sunnuo, who was once a carpenter, favors carving the eight auspicious symbols in Tibetan Buddhism on his pottery.

"Both crafts produce new things, yet making pottery is comparably easy and makes more money," Larong says.

Sunnuo's 17-year-old grandson and 22-year-old son-in-law are among the youngest of the village's craftsmen.

"Most of the youngsters are not willing to learn. They would rather be in the transportation business, which is booming thanks to the ongoing construction of the No 214 national-level highway nearby," Larong says.

But Sunnuo does not want his relatives to do such a "dangerous" job and would rather they develop the skills that have been handed down through the family.

Five years ago, Guo Junhua, a provincial-level pottery producer, co-invested in a small company and wanted to cultivate apprentices.

Villagers voluntarily sign a contract with the company, which then takes charge of order and sale procedures.

"Without such worries, the craftsmen can focus on enhancing their skills and developing new pieces," Guo says.

Sunnuo was again invited to be one of the instructors.

During the first nine months, apprentices receive a subsidy of 200 yuan a month. If they prove themselves suitable, they can stay on with a salary. Otherwise, they can choose to either leave or continue learning without a subsidy.

But, there were only two apprentices this year.

In Tibetan culture, women are not actively involved in business, resulting in no female pottery makers. Sunnuo and Guo are considering breaking this convention.

"Many reputable pottery masters around the world are women," Guo says.

He is also considering replacing the traditional open-fire firing with electronic kilns as he says this is more environmentally friendly.

"Refining technology, improving quality and developing new pieces, especially high-end ones are essential. In that case, more youngsters will be attracted to the craft," Guo says.

"Increasing profits is a must. You have to prove to others this is a promising field," Sunnuo says.

|

A black pottery tea set. |

(China Daily 10/19/2010 page20)