Focus

Bidding fashionable farewell to the dead

By Phoebe Cheng (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-21 07:48

|

Large Medium Small |

|

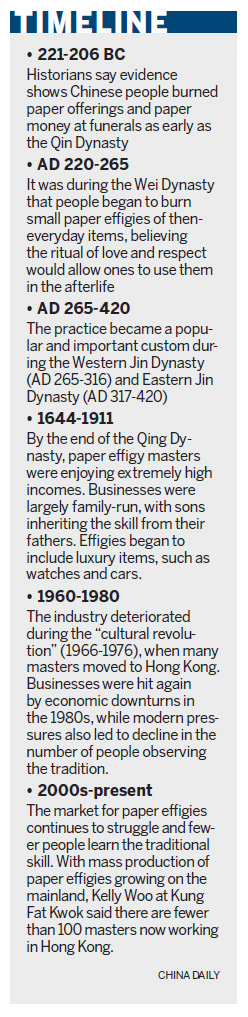

Paper replicas of modern-day items made at a ming zhi pu, ghost money shop, in Hong Kong to be burned as offerings to the dead. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

How traditional ritual is getting a modern makeover. Phoebe Cheng in Hong Kong reports.

The shelves inside Au Yeung Ping-chi's store are chocked full of the latest gadgets and fashions, from high-tech smart phones and digital cameras to limited-edition sneakers and brand-name handbags.

Get closer, however, and you will see each one is a carefully crafted paper effigy made to look like the real thing.

Welcome to one of Hong Kong's most modern ming zhi pu, or ghost money shops, where Chinese shoppers regularly buy paper gifts to burn for dead loved ones to use in the afterlife.

Au Yeung decided to tweak the traditional service and follow the latest consumer trends after taking over the family business from his father.

"When I made my first electronic dance mat (out of paper), my father didn't even know what a dance mat was," said the 33-year-old, who started working at the shop in Sham Shui Po after graduating from design school about 10 years ago.

Once he had mastered the ancient handicraft, Au Yeung began applying his innate sense of creativity to combining the old with the new and making effigies that are chic and relevant to today's society.

"He gave me the freedom I needed to use my creation on this age-old handicraft," he told China Daily as he looked over at his aging father, who sat by the entrance of the shop chatting with other staff members in his faint and raspy voice.

"I wanted to stand out (from others) in the industry by selling paper effigies that are not commonly found in shops," said Au Yeung, whose workbench was covered in piles of colored paper and pots of glue for his latest work, a handheld Ninendo DS games console.

For Hong Kong shoppers, Au Yeung's store does stand out. His trendy works have already attracted the attention of people with relatives who died at a young age.

The store receives several orders from customers who want custom-made effigies of fashionable items, including cell phones and accessories.

Up in smoke

Au Yeung is the second generation of his family involved in the paper effigy business, although the Sham Shui Po store he now runs has only been open since 2007 (his father relocated from Hung Hom about 30 years ago).

Back then it was common to see families in Hong Kong and across the rest of China burning paper offerings in passageways between residential buildings or on the roadside, particularly during Ghost Festival, which is in the seventh month of the lunar calendar, and Qing Ming Festival, also known as Tomb-sweeping Festival.

These rituals have been practiced since ancient times and many people believe that the burned paper effigies (traditionally money) will help loved ones in the afterlife.

However, people today are growing more concerned about the environment and the tradition is less commonly seen. Critics say the smoke from incense and paper offerings creates air pollution, while others argue it is simply a waste of paper.

"Environmental concerns have had an effect on our business," said Au Yeung. "People are burning less."

Although there are no regulations in Hong Kong that restrict burning paper offerings indoor, a growing number of property management companies have banned tenants from practicing the ritual in most public and private residential blocks, as well as all newly built properties.

"Offering paper effigies is the best tradition in the Chinese culture," said Cheng Ming-leung, chairman of the Chinese Paper Merchants Association.

He said he is confident the precious tradition can be saved and recommended that, if today's luxurious properties do not allow the practice, people should go to temples and sanctuaries that have incineration facilities.

Online push

Despite the struggles faced by the industry, many ming zhi pu are boosting their businesses online.

One of them is Kung Fat Kwok, which is also based in Sham Shui Po and sells a range of Buddhist ritual tools and paper offerings. The company launched its website - yp.com.hk/kungfatkwok - two years ago.

"The website attracts younger customers and people from overseas," said Kelly Woo, who joined the family-run business when she married her husband, Neil Leung, 43. "There were just no shops selling these tools and paper effigies."

After offering their products online, she said Kung Fat Kwok has seen sales increase by 10 percent.

Woo said she has no problem with the industry's move toward technology, adding that although business is not as robust as in the past, she feels the tradition will survive in the long term.

"People may burn less paper offerings today but I do think the tradition will stay," she said. "Many young people come into our shop at the beginning of the year and buy things that are believed to offer good luck throughout the year."

Although Woo's experience suggests the Web could have a positive effect on her income, master craftsman Au Yeung said he is concentrating his efforts on the product.

"I have to make the paper effigies exactly according to the requests of my clients," he said, explaining that a customer once asked him to make a specific Sony notebook computer. "He insisted on Sony, so I had to produce a paper handicraft that was exactly the same."

Clients have also been known to order dishes from famous restaurants, such as black pepper chicken wings and sour and spicy pork rice noodles from Tam Kee, a popular Hong Kong eatery.

"When I get an order like that, I'm in trouble," admitted Au Yeung. "I can't eat spicy food."

To make the effigy as accurate as he could, he had no choice but to buy the dish and imitate its appearance - and as he did not want to waste the food, he had to eat the spicy rice noodles himself.

"It was so spicy I almost called an ambulance," he joked.

He admitted he treats his job as seriously as a surgeon, putting his heart and mind into every creation. "If I fail to make an effigy that looks like the real thing, I'd be in trouble," said the craftsman, who eventually sold the paper spicy noodles for about HK$400 ($50).

"I not only need to please the customer but also the person who is receiving the gift in the afterlife," he added.

|

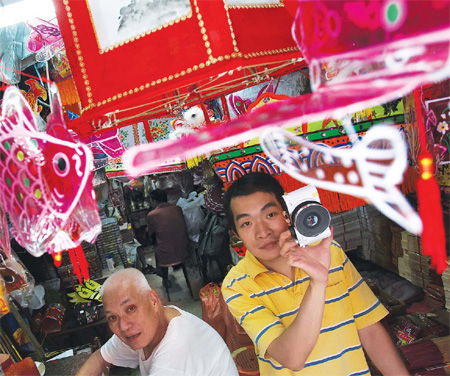

Au Yeung Ping-chi, right, and his father at their family's ming zhi pu, or ghost money shop, in Hong Kong. The 33-year-old makes modern paper offerings to be used during traditional rituals. Photos by Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

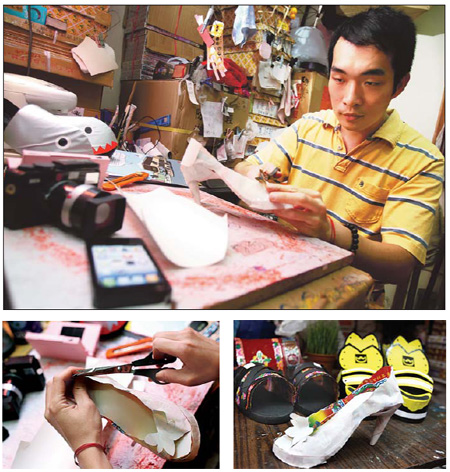

Au Yeung Ping-chi makes a pair of "high heel shoes", just one of a range of modern paper effigies he has been commissioned to make by customers. Chinese burn paper offerings for deceased loved ones. |