Life and Leisure

Profiting from tradition

By Zhang Zixuan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-10-25 07:58

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Age-old needlework finds new life in the skilled hands of an embroiderer at the First China Intangible Cultural Heritage Exhibition in Jinan, Shandong province. Cui Pengsen / For China Daily |

|

Zhou Shuangxi, from Jiangsu province, demonstrates the working of the Dahualou Yunjin loom to produce the famed Yunjin brocade. Photos by Zhang Zixuan / China Daily |

|

Yang Zhi, from Henan province, even today uses a pottery wheel driven by a stick, to produce fine Jun porcelain. |

|

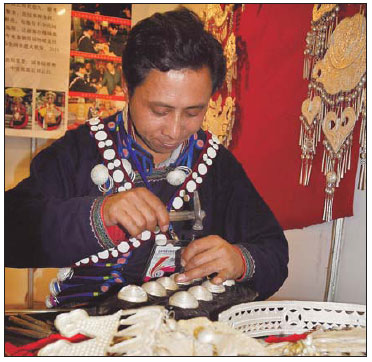

Naigu Shagui, from Sichuan province, works on silver accessories of the Yi ethnic group. |

Many handicrafts are disappearing even though they are part of the country's intangible cultural heritage, but help is at hand. Zhang Zixuan reports

Though they enjoy the title of intangible cultural heritage, many traditional Chinese handicrafts are disappearing. In response, the idea of "productive protection?has been suggested, which involves making intangible cultural heritage products a profitable business.

Guided by the concept, the First China Intangible Cultural Heritage Exhibition was held in Jinan, Shandong province. It ended Oct 18.

About 622 intangible cultural heritage items were sold for 11.96 million yuan ($1.8 million). More than 500 development projects were inked, with a trading volume of 43.2 billion yuan ($6.5 billion).

"Productive protection encourages intangible cultural heritage to be marketed without losing its character," says Zhou Heping, head of the National Library and former vice-minister of culture.

"It brings financial benefits to handicraft inheritors and promotes intangible cultural heritage to the public."

"Unlike over commercialization or destructive development, productive protection harmonizes traditional handicrafts and modern life," says Lu Pintian, a researcher at the Chinese National Academy of Arts and dean of China Arts and Crafts Museum.

Productive protection is mainly applied to traditional handicrafts such as needlework, woodcarving and paper cutting.

"Manual work is the core of productive protection," Lu says.

The Nanjing Yunjin, for example, one of the three major kinds of brocade in ancient China that goes back more than 1,500 years, is still made by the hand using Dahualou Yunjin loom (5.6 meters long, 4 meters high and 1.4 meters wide).

Favored by the royal family during the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties (1271-1911), Nanjing Yunjin is characterized by exquisite patterns and rich colors, and uses rare materials such as gold, silver, silk and peacock feathers.

Nanjing Yunjin patterns are designed and controlled through complicated compositions of knots of silk thread.

"It is like programming on the computer," says brocade-maker Zhou Shuangxi. "The quantity of knots depends on the complexity of the pattern. A dragon robe requires a knot composition many tens of meters' long."

Once the design is fixed, the luxurious brocade is then produced by two workers with the Dahualou Yunjin loom - a weaver weaves the satin and a jacquard worker sitting on top of the loom adds patterns on the satin.

Weaving methods called "swivel coiled weaving" and "varying color from flower to flower" are unique to Nanjing Yunjin and cannot be copied by modern weaving machines even today.

Productive protection, says Zhou Shuangxi, can help intangible cultural heritage items fit into contemporary society and bring profits to its inheritors.

"Traditional handicrafts were generated at first as a means of survival. Their existence was based on certain utilitarian purposes," researcher Lu explains. "A craftsman's enthusiasm is bolstered when his products are appreciated and consumed."

A good example is Fan Jimei, one of the successors of the Tancheng wooden toy makers.

Fan, a farmer from Fannian village, Tancheng county, Shandong province, says the Fan family's ancestors settled in the village when Chenghua was emperor (1465-1487) - and this is when Tancheng wooden toys were first made.

These wooden toys are vividly colored and have a simple but smart mechanical design that enables the toys to move and make noises.

On the first day of the exhibition, more than 300 of Fan's handmade toys were sold, which cost just 3 or 4 yuan each.

The toys used to be made in the off-season for farming but have now become a major source of income, bringing in about 10,000 yuan a year.

Fan teaches his son and daughter-in-law to make wooden toys, but he says it's not so much an art to him as a way of making a living.

"The exhibition made me realize the huge potential market of traditional handicrafts, which makes me want to carry on," Fan says.

On the other hand, however, some scholars warn that productive protection is not commercialization and industrialization of intangible cultural heritage.

"The priority of productive protection is to protect, not to produce. Balance between the two needs must be maintained," says Qi Qingfu, a member of the National Expert Committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection and professor of Central University of Nationalities.

Qi uses the Sama Festival of the Dong ethnic group as an example. Sama is a sacred festival in Guizhou province, which is supposed to be celebrated once a year by the Dong people. In order to promote tourism, however, the county government arranged residents to celebrate the festival four times a year.

Another case is thangka, the traditional handmade paintings of the Tibetan ethnic group. A good piece of thangka usually takes one year to finish and therefore costs about 100,000 to 200,000 yuan. Now, owing to demand, printed fakes are produced and sold for 20 yuan.

"Fakes are very destructive. When thangka becomes an instant product, the original one dies," Qi says.

Yang Zhi, representative inheritor of Jun porcelain, from Yuzhou, Henan province, tries to balance the demands of the market with heritage protection.

The 63-year-old master started learning Jun porcelain making at 14 and still uses traditional methods.

At the exhibition, he and his student demonstrated how to make Jun porcelain bodies on a pottery wheel, driven by a wood stick.

"Some people wonder why I still use the wood stick rather than electricity to drive the pottery wheel. The answer is very simple: That's the way the handicraft was born, and it's part of the core value needed to be passed on," Yang says.

Yang sticks to tradition when it comes to glazing and firing as well.

As one of the five most celebrated porcelain kilns - along with Ding, Guan, Ge and Ru - in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Jun kiln porcelain is most valued for its yaobian, or furnace transmutation.

Owing to the uncertainty of the reduction of copper glaze in kiln firing, the color tints of Jun porcelain can be unpredictable.

"The body is the basis of Jun porcelain, while the glaze is its spirit," says Yang.

In the past, the rarity of Jun porcelain was attributed to its high failure rate, which used to be up to 90 percent. It remains hard to produce to this day.

"Today's art will be tomorrow's antique," the Jun porcelain master says. "When we leave the mark of time on our work, we create history."

The market appreciates Yang's efforts. His Jun porcelain company makes more than 10 million yuan a year. At the exhibition site, six of his works fetched about 300,000 yuan, even before the exhibition opened.

"When you are true to tradition, the market recognizes it," Yang says.