Life and Leisure

Face of hope

By Liu Xiangrui (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-03 07:50

|

Large Medium Small |

|

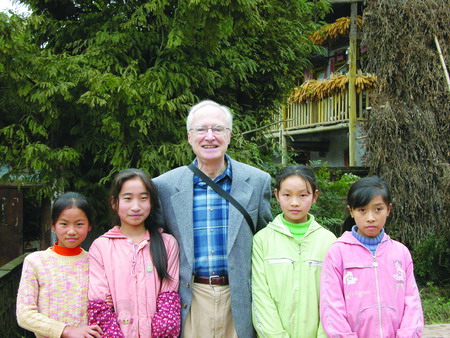

Julian Taplin poses with students at the school he and a Hong Kong businessman rebuilt in the mountains of Tianquan county, Sichuan province. Provided to China Daily |

A school whose roof was once patched up with cardboard is now a three-story building outfitted with Internet-enabled computers, a canteen and dormitories. Liu Xiangrui reports

The moment you evince the slightest interest in his school, Julian Taplin will whip out his self-made DVD and play it. And then, the 74-year-old psychologist and educator from the United States will patiently take you through each of his students, recounting their names, grades and their family backgrounds. The school Taplin is so passionate about is hidden deep in the mountains of Tianquan county, Southwest China's Sichuan province. When Taplin first saw the school in 2005 during his annual trips to China to promote the mental-health education of children, the school was in dire straits. Refitted from a dilapidated old temple, it had only five part-time teachers for 95 students.

With a monthly income of no more than 300 yuan ($45), the teachers had to double as farmers to make a living. They lived in the attic of the old temple, whose roofs and walls had been patched up with cardboard to keep out the rain and wind.

Its students trudged through treacherous mountain roads for hours everyday to reach the school. Many of those who could not afford even its meager fees, simply dropped out.

"I was touched by their innocent smiles and became determined to improve their schooling," Taplin recalls.

In 2006, he met a Hong Kong businessman, Wang Bin, through one of his students, Zhang Xiangrong. Moved by Taplin's plans, Wang joined hands to rebuild the school.

"I built the dormitories and the cafeteria while Wang helped with half the classrooms," Taplin says, giving much of the credit to his partner.

Put into use in 2007, the new school has a three-story teaching building with multimedia equipment in every classroom, a lab with 22 computers connected to the Internet, dormitories for both students and teachers, and a canteen. Taplin donated several thousand books to its library, and a camera for children to learn photography.

Hosting more than 200 students and 12 teachers, the school is a big attraction for parents far and near. They are drawn by its quality of education, facilities, and the stories of what the "laowai" (foreigner) has done for the children there, according to one of its teachers, Li Chenglin.

In August, Taplin published his 18th book in China, titled In My Previous Life, I Was a Chinese, a biography focusing on his experiences in the country. Taplin first visited China in 1982 and in the 1990s joined the Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences as a guest lecturer.

"It is not a recent saying," Taplin says, referring to the book's title. "I have said it for at least six years, and it has no religious connotations. It's simply a statement of being amazed at how well I seem to fit in with Chinese culture and, above all, with so many friends and young students.

"For years I have been happy in China. A lasting joy for me is that I have been a personal partner of countless Chinese children, adolescents and families as they climb upwards, and it's time I do something to say 'thanks'."

When the 2008 earthquake hit Sichuan and nearby regions, Taplin's health did not permit him to come immediately.

"I understood that many places where I had taught suffered grievously - it was probable that students I had talked to, shaken hands with, and waved to, had been crushed to death," Taplin recalls.

Slowly, word came through that his school was unhurt, but Shiyang middle school, where he had lectured before, had lost most of its classrooms and hundreds of students.

Right after an operation in July 2008, Taplin traveled through towns and villages to help with the psychological rehabilitation of the students. "I was impressed that there was so little open shock or psychological disability," Taplin says.

"For me, the most poignant moments were when I got a question such as, 'When, and how, should we tell our child that her precious auntie is really dead and will never come back?'" Taplin says.

"I could feel the cold rock of grief about to fall on the little ones, and I worked hard to hold my tears and give practical suggestions that they could understand."

On hearing that one young girl needed urgent treatment for a bone tumor in 2009, Taplin stepped in with 7,000 yuan ($1,050).

"He's not rich, but he has saved his earnings from lectures and book royalties to buy equipment for our school and clothes and presents for our children," teacher Li Chenglin says.

Taplin's dozen books for children includes Three Skills for Success, which won the prestigious Bing Xin Prize for Children's Books in 2007.

"His books are specially tailored for Chinese students," says Hou Shuiping, dean of the Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences. "They are very practical, interesting and rich in content."

Taplin says the growing interest among Chinese in overseas education reflects the widespread idea that China's education system cannot build creative leaders with its excessive homework load, and focus on cramming and examinations.

He, however, cautions against copying the West blindly, saying the costs could far outweigh the benefits.

"The current Chinese education system has some strengths," Taplin says, citing what he calls its "orderliness and seriousness".

"But the system drives out the training and experiences that can advance leadership skills and creativity; it wastes 'late bloomers', by keeping them out of key pathways."

Taplin says his efforts to help children in China has not ended yet. When doctors told him he had chronic leukemia in 1995, he thought deeply about his remaining years.

"My goal is to be a ladder so that other people can climb higher. I don't care if the ladder has my name on it or not," he says.