Life and Leisure

Unsung heroes

By Wen Chihua (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-17 07:59

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Chinese captives of the Korean War (1950-1953), fought fierce ideological battles to be returned to the mainland, only to be branded traitors for not fighting to the end - till they were rehabilitated in 1980. Wen Chihua from China Features reports

Zhong Junhua was kneeling on the riverbank, slurping water out of his cupped hands when he felt a gun jabbed into his back. He turned to see two American soldiers. "At that moment, I was scared, and wondered if I would make it home alive, if I would see my family again," he recalls. He would, but not before suffering horrendously in captivity. The story of Zhong's fall from grace starts before the war, when the then 17-year-old, a People's Liberation Army medic, fought bandits in his hometown of Chengdu, Sichuan province, in the summer of 1950. He was decorated for his bravery in saving wounded soldiers.

"I felt deeply honored and believed the Party treated me as a loyal fighter, even though I didn't know how to shoot," recalls the 77-year-old pensioner at his home in Chengdu.

It was a feeling that would change as the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950. The conflict quickly spread when the United States-led UN forces crossed the 38th parallel.

At this point, China entered the war on Oct 19. It would eventually send 780,000 soldiers of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army.

Zhong went to war in December as a medical corpsman of the 538th Regiment, the 180th Division of the 60th Army.

"I was ready to be decorated and bring more honor to my mother," he recalls.

Zhong joined the fighting during the first and second phases of the 5th Campaign, China's last major assault of the war.

Medical corpsmen like Zhong did not receive weapons, because they had to carry food and medicine.

"Our main task was giving first aid to the wounded and taking in soldiers who were sick and falling behind," he says.

During a retreat, they saw the silhouette of a man sitting on a ridge. Zhong went to check on him when he didn't respond to their calls.

"His head was missing. His two infantry packs kept him upright even though he was dead."

His medical unit took in more than 20 sick and wounded that night.

"We were highly praised by the regiment leaders, and I felt very happy indeed."

But neither praise nor happiness would follow a fateful retreat.

|

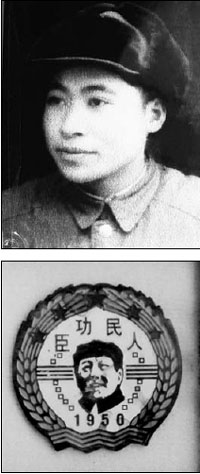

Upper: Zhong Junhua in his Chinese People's Volunteer Army uniform. Above: The medal Zhong won in 1950 for his bravery in saving wounded soldiers. |

"During the first phase (of the 5th Campaign), the Chinese army did very well, repelling the US-led troops past the 38th parallel to Seoul," says Shuang Shi, expert on the Korean War and author of The First War after the Founding of the People's Republic of China.

But, during the second phase, he says, the Americans had already learned the weakness of the Chinese military operations: Chinese soldiers carried food and ammunitions that only lasted a week.

"The Americans lured the Chinese army deep south. When we were about to run out of supplies, they waged a sudden counterattack. The Americans had mechanized forces, were well-equipped with jeeps and tanks, and moved very fast."

Zhong's division of 10,000 fighters was virtually destroyed, with many soldiers killed, and 5,000 captured in late May 1951.

After days of hard fighting, fragmented troops tried to break out of the siege.

Zhong followed his squad leader and about 100 other medical personnel for a few days.

One rainy day, he saw a jar of soybeans soaking in an empty house.

"I grabbed a handful and ate like crazy. I was hungry, cold and exhausted, and fell asleep in the rain," he recalls.

He woke up to find himself alone.

That was when he went to the river and was captured.

He was soon transferred to Geoje Island, where the US military was holding 170,000 prisoners of war (POWs), including 20,000 Chinese.

Prisoner exchange became the primary stumbling block of the Panmunjom Truce negotiations in 1951 and 1952. Under the Geneva Conventions of 1949, two warring parties must exchange all prisoners immediately when hostilities end.

While anti-mainland sentiment was high at that time, Americans insisted that Chinese POWs should choose "out of their free will" between going to Taiwan and the mainland.

In the island's four camps - numbers 71, 72, 86 and 602 - camps 72 and 86 were controlled by Kuomintang (KMT) supporters. No 71, where Zhong was held, was under communist influence, recalls Chen Zhilong, a low-ranking officer of the 34th Division of the 12th Army, who was also captured in May 1951. Ideological conflicts raged among the POWs.

"The fighting was really fierce," says Chen, now 80. "What we went through was horrific."

"The Americans convinced some turncoats by offering to send them to Taiwan after the war. We patriots had to stand up and be counted, and prove our desire to return to the communist-run mainland," Chen recalls.

KMT supporters tortured and murdered those who persisted in returning to the communist mainland, he says. Some POWs were tattooed with "anti-revolutionary slogans" on their arms, anti-communist statements on their backs and KMT flags on their chests.

Chen's comrade in Camp 72, Lin Xuebu, was 22 when he was murdered on April 8, 1952.

"They cut open his chest and kicked his belly. His heart burst out. He was yelling, 'Send me back to the motherland!' before he died a martyr's death," Chen says.

Zhong recalls that his comrades in Camp 71 fought back by raising the first Chinese national flag on Geoje Island. It was considered such a triumphant event by desperate Chinese POWs that its details were recorded in the several memoirs written by captives and researchers. Award-winning writer Ha Jin also describes the event in his book, War Trash.

They managed to get some US military trench coats and obtained the white nylon by baking the trench coats on a barrel, then scratching off the green rubber surface.

"We tried to dye the cloth with our blood. But it turned reddish black when the blood dried," Zhong recalls.

The Korean comrades working in the camp clinic smuggled some mercurochrome (a brand of merbromin, a topical antiseptic that leaves a red stain), so the cloth could be dyed red, and some quinine to color the five yellow stars on the flag.

As the youngest, Zhong and He Pinggu were selected for the flag-raising honor. Zhong says he told his comrades that should the mission fail, his only wish was for his body to be wrapped in the flag and send back to the motherland.

On April 8, they rushed out to hoist the flag on an iron wire strung across several petroleum barrels. As the Chinese sang the national anthem, the guards fired and three Chinese were wounded. On that day, Camp 71 became known as "Little Yan'an on Geoje Island". Yan'an, Shaanxi province, had been China's revolution base before 1949.

More than 6,000 Chinese prisoners followed by raising nine national flags in other camps.

"The enemy drove 11 tanks into the camps, killing 65 and severely wounding 102," Zhong recalls. "It shook the world."

After the armistice was signed in July 1953, some 7,000 Chinese POWs returned to the mainland. Zhong was released on Aug 6 and sent to the Panmunjom POW exchange point.

"We burst out crying when we saw the arch printed with 'Entrance to the motherland'," Zhong recalls. "We took off our prison uniforms and ran through."

But once home, the POWs were considered traitors for not fighting to the death. About 90 percent were expelled from the Party or dishonorably discharged.

As a medic, Zhong had not learnt to use weapons or how to react if he was captured. He had taken two grenades from dead comrades, but couldn't detonate them before the Americans took them.

"We wanted to be a hero or die in war," Chen Zhilong says. "I didn't become a hero, nor did I die. How awful it was to be a POW."

Chen and Zhong were expelled from the Communist Youth League, and their service during the Korean War was deleted from their records. Chen was denounced as a suspected KMT spy, his work and home were monitored.

In 1980, the central government issued a document rescinding verdicts against Korean War POWs. Chen's and Zhong's expulsions from the Communist Youth League were stricken from their records and their service in Korea added.

Chen, who retired as deputy director of the general service section of Sichuan Cotton & Linen Co in 1998, now lives with his wife on their 4,000-yuan ($603) monthly pension.

His son and daughter work in the construction, and storage and transport businesses. "They buy us nutritious food and anything we need, so I'm quite satisfied with life now," Chen says.

"I don't regret volunteering for the war" Chen says, fighting back tears.

Zhong, who retired as Party Secretary of a Chengdu department store in the early 1990s, puts it this way: "Getting captured doesn't mean one is not a true soldier."