Life and Leisure

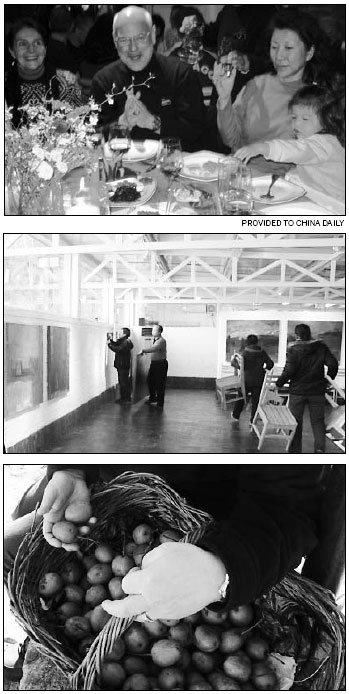

A Ming Dynasty Thanksgiving

(China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-29 14:06

|

Large Medium Small |

Spear, fed up with corporate life, had just quit his job, cashed in his stock options and was casting about for something new to do, so he gladly took up his friends' requests.

As the number of expatriate country homes in Mutianyu grew, the local government took notice. The village head asked for a meeting with Spear.

"I was a little scared," says Spear.

But the head just wanted to see if there was anything Spear could do to help the village, which had no good long-term jobs and was losing most of its young people to urban Beijing.

Spear hit upon the idea of a Western restaurant combined with an arts room and sold his wife, Upton-Wang and others on it.

Upton-Wang readily admits her first look at Mutianyu's old, unused elementary school didn't inspire her with the same vision as Spear.

"I was struck by what a mess it was," she says.

But they carried on and The Schoolhouse proved such as success that five years later, the operation has expanded to include two other restaurants (the Roadhouse and Xiaolumian), a hotel and conference center (the Brickhouse) and homes to rent by the night in Mutianyu and the surrounding villages.

The whole operation aims to be as sustainable as possible and has already won several accolades for its efforts.

Forty percent of management staff and almost 100 percent of other employees are from the local township. Food is grown, bought and sourced as locally as possible (the only imported foods the kitchen uses are canned tuna, prepared mustard, olive oil and some dairy products). Old buildings are refitted rather than knocked down. All the rental houses and restaurants have a filtration system built-in so that tap water is drinkable, helping cut back on plastic-bottle use.

Spear admits that even with the awards, the operation still isn't perfectly sustainable, but he adds that it is constantly improving small things, which over time adds up to a big difference.

Some people have criticized The Schoolhouse for being a for-profit business, Spear says, but he believes long-term economic viability is part of being sustainable and makes no bones about earning money.

"We pay fair wages. I have no shame in making a buck. I don't think there's anything wrong with it," says Spear.

The Schoolhouse and related ventures have brought about $10 million of outside investment into Mutianyu, he says.

"Does that mean everybody around the village loves us? I'm sure not. No. There's friction and there are differences, but I think there's mutual respect," he says.

The Schoolhouse also promotes "slow food": Spear had 500 people come out for a Slow Food Saturday this summer, and they went around to different restaurants in nearby villages sampling local food.

Some people complained that there was a lot of fried food, but Spear says that's part of Chinese cooking tradition and that "slow food" doesn't involve a specific means of preparation, it simply means that food is harvested, produced and enjoyed locally.

"There's nothing wrong with fried food, for heaven's sakes," he says.

The slow food concept is about sitting down with friends and family, enjoying food, knowing where that food came from and knowing what's in it, adds Spear.

It's a concept that dovetails well with Thanksgiving dinner, which was once again last week enjoyed at Mutianyu by a large group of family, friends and guests in a warm, welcoming atmosphere.

"I just love that vibe," says Saint Cyr.

The family feeling at The Schoolhouse make it the next best place besides home for expatriates to be at Thanksgiving, adds Saint Cyr.

And of those happy to be around the Spears' Thanksgiving table, Spear says it's he who feels luckiest.

"I sure have a lot to be thankful for," he says.