Focus

Shantytowns face hard home truths

By Fu Lei (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-13 07:58

|

Large Medium Small |

|

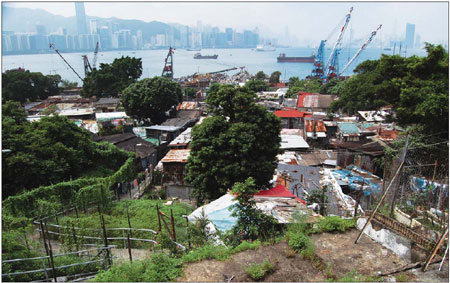

Cha Kwo Ling, one of the shantytowns in Hong Kong, overlooks the iconic Victoria Harbour. There are a total of 393,000 shanty structures in the SAR, most in the northern New Territories. Photos by Fu Lei / China Daily |

|

A corner of Cha Kwo Ling in eastern Kowloon that is home to 3,000 people. The area has long been a major settlement for the Hakka ethnic group and mainland migrants. |

Residents brace for uncertain future as development looms, reports Fu Lei from Hong Kong.

Lily Tse's dilapidated hillside home is in the middle of a labyrinth of straggling shacks rigged with corrugated metal, wooden planks and other scrap materials.

Here, roofs are often just thick tarps weighted down with bricks, while electrical wires dangle overhead, tangling outside homes with television cables and clotheslines.

Even the most detailed map of Hong Kong does not clearly trace the boundaries of Cha Kwo Ling in eastern Kowloon. Not because many of its houses are too small and scattered, but because its haphazard sprawl is almost impossible to delineate.

"My house could have stood for a hundred years. I'm not sure how much longer it will last, though," said 65-year-old Tse, one of about 3,000 people who still live in this village, flanked by glitzy skyscrapers.

Talk of redevelopment has circulated for several years, yet for many residents the future remains far from certain.

Although demolishing the village could help some escape the rough and unsanitary conditions, others could potentially be left homeless.

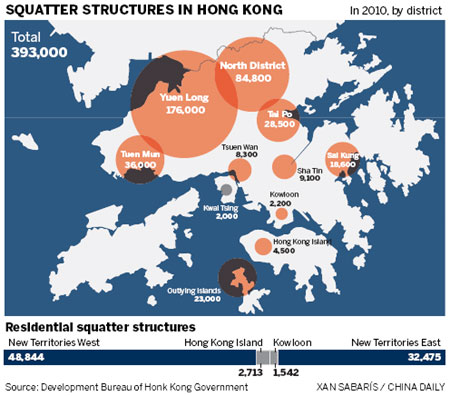

There are 393,000 shanty structures throughout Hong Kong, more than 85,000 of which are used as homes, according to the Special Administrative Region's (SAR) development bureau.

Under local law, the buildings are technically illegal. As they are neither private properties nor public housing, they are given special dispensation from the government to remain.

"The formal name is 'tolerated structure' but I give them another name: zinc-clad structure," said Kenneth Ip, 63, an amateur historian who grew up close to Cha Kwo Ling.

Tse runs a tiny cafe on the ground floor of her gable-roofed stone house, living with her husband in the attic above.

The building could date back to the early days of colonial rule, but all she knows for sure is that her father-in-law at some point managed to acquire it and open a cafe, which she took over in the 1980s.

The shantytown, which overlooks the iconic Victoria Harbour, sits between two busy subway stations and adjoins a vast estate of high-rise apartment blocks.

The area has long been a major settlement of the Hakka ethnic group, who established a quarry in the stone-rich area a century ago. Makeshift shacks started to mushroom in the 1940s, as refugees streamed in from the Chinese mainland to escape the civil war. At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, the community was home to more than 10,000 migrants.

Although the number of residents began to shrink in the 1980s, the shanties stayed standing. Plans to raze the area and build a new residential community have so far come to naught, although any such development could be a double-edged sword for residents.

As Tse's house is technically illegal, she and her husband are unlikely to receive any compensation from the government if officials chose to demolish it. The only benefit would be getting "priority status" for public rental housing, which would significantly cut the waiting time.

Waiting game

A watershed for Hong Kong's shanties came in 1982 when the regional government conducted a survey of all existing squatter structures, the materials that went into them and the surrounding neighborhoods.

No new shanties have been permitted since then but dwellings built prior to that are tolerated until redevelopment begins.

Qualified residents of shantytowns have been told they will be re-housed in public rental apartments; however, such properties are in short supply.

Almost one-third of Hong Kong's 7 million residents live in its 710,000 public rental homes, according to official statistics.

In his annual policy address last month, Donald Tsang, chief executive of the SAR, vowed that the government will shorten the average waiting time for a public accommodation to three years by allocating enough land for 15,000 new apartments every year.

Ip said the government has so far "ceased its large-scale eastbound development in New Kowloon, which started in the 1930s and lasted for half a century". (Cha Kwo Ling lies to the far east of New Kowloon.)

If the government does redevelop Tse's village, residents would be given two years' credit by the housing authority, which would theoretically slash the waiting time to about 12 months. However, not everyone will be eligible.

"To qualify, at least half of an applicant's family must have lived in Hong Kong for seven years," said Ng Yin-cham of the Neighborhood Advice Action Council, a government-backed organization offering consultancy services to the "most helpless people".

"A considerable number of dwellers are migrants from the Chinese mainland," he said. "Their wives and children may have come to Hong Kong later and have not been here for seven years."

Tse has lived in Hong Kong for decades but most of her children and grandchildren are now in Guangzhou, capital of South China's Guangdong province.

In fact, the 65-year-old said that, despite the hardships, she does not want to move from the community she has laid down her roots.

"My house is cozy, and I pass the time of day with my neighbors," she said, smiling. "In a public housing estate, the doors are all shut. People don't even know each other."

Every afternoon, locals flow into Tse's cafe for snacks, drinks and conversation. Inside are six wooden tables fixed to the floors, while among the decoration is an old, yellowed advertisement poster.

The shantytown offers more than just a relaxed ambience, though. "The location is ideal: sitting on a hill and facing the sea," said Tse. "Transportation is also convenient."

Good with the bad

Yet, for every pro there is a con. Although the four-lane highway running in front of Cha Kwo Ling has several minibuses carrying commuters to the two nearby subway stations, the majority of vehicles using the route are heavy-duty trucks carrying concrete and steel containers.

A lot of the traffic is heading to the metal recycling plant at a walled quay on the other side of the road or a small paper recycling center in the shantytown.

The proximity to the harbour, while providing a costal vista and balmy breezes, also exposes the fragile shanties to the gales that hit Hong Kong every summer and autumn.

Like most shantytowns, the village does not have even basic facilities, such as a gas supply, which means residents have to use liquefied petroleum gas cylinders for cooking and bathing.

Arguably the worst problem is the lack of private toilets. The underground drainage pipes beneath Cha Kwo Ling are too narrow for human waste, so locals use public toilets on the outskirts.

"Only those who ignore the interest in public health would build indoor toilets (here)," said a 72-year-old woman who declined to give her name. "The hygiene (in the village) is not good in general. My tin house gets stifling in the summer."

The woman, who settled in the area after moving from the Chinese mainland in 1962, said she and her 80-year-old husband have recently applied for public rental housing.

With densely packed buildings, narrow passages and highly flammable building materials, fire hazards abound in Cha Kwo Ling.

"We have fire accidents almost every year," said Tse, whose village witnessed three fires in just one month in 2006, leaving hundreds of residents homeless.

It was a sweeping fire at a settlement in Shek Kip Mei in late 1953 that displaced some 53,000 people that prompted the then-colonial government in Hong Kong to introduce the public housing system.

Despite the danger, Tse insists the only thing that will make her abandon her house is "if it is demolished".

Like most others in the village, she and her husband would be unable to afford the cost of living in other areas of the SAR, let alone afford the rent on another cafe.

"Even public rental flats will charge us," said Wu Wai-yuk, a mainlander who arrived in Cha Kwo Ling in the 1980s. "I'd rather save the money."

"Zi li geng sheng", she said, a slogan widely known among those born in the era of former leader Mao Zedong that roughly translates as "rely on yourself to change your own life".

"I don't pin my hope on others," added Wu.

(China Daily 12/13/2010 page1)