Life and Leisure

What lies beyond

By Chitralekha Basu and Guo Shuhan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-17 08:06

|

Large Medium Small |

|

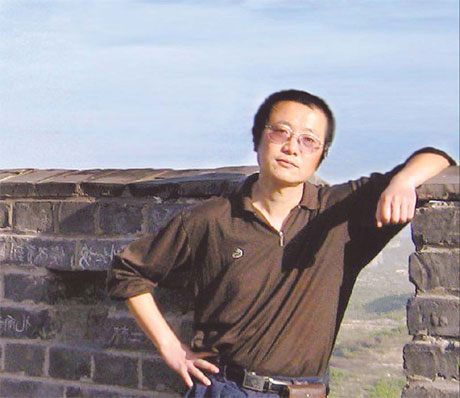

Liu Cixin, hailed as the face of China's sci-fi writing, at the Great Wall, during his trip to Beijing. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

Liu's Three Body trilogy - Earth Past, Dark Forest and Dead End - is acclaimed for its extraordinary artistic vision. |

Nation's most prolific and popular sci-fi writer says he writes for the masses and is simply driven by a never-ending curiosity. Chitralekha Basu and Guo Shuhan report

Liu Cixin is self-effacing to a fault. When we met him on a gloomy December morning in the Spartan offices of Science Fiction World in Chengdu, he spoke in a mild voice, hardly ever meeting the interviewer's eye.

His reserved demeanor is quite unlike that of some of the characters he creates - the vainglorious artist, the mercenary scientist or the astrophysicist Ye Wenjie in the first book of the trilogy Three Body: Earth Past who, on an impulse, connects with the aliens, daring them to attack the Earth (see sidebar "Liu Cixin: Career milestones").

Given that Liu is eight-time winner of the Galaxy Award for science-fiction writing and recently won the first Xingyun (Nebula) Awards given by the World Chinese Science Fiction Association, jointly with fellow writer-critic Han Song, a hint of vanity would not be out of place.

But Liu, widely acknowledged as the face of China's sci-fi writing, keeps trying to tone down the halo surrounding a much sought-after writer. He writes for the masses, he says, and is concerned, primarily, about popularizing science. His work is more in line with the racy sci-fi flicks, he says.

"I am not a literary writer," he reiterates. "If my writing seems invested with such elements I would give the credit to the translator (in this case, Joel Martinsen)."

Most of his peers engaged in writing, documenting and critiquing sci-fi in China at this moment disagree. They are saying it especially loudly since his latest book, the much-awaited final volume of the Three Body trilogy, was launched on Nov 27. Dead End, in which the aliens of Three Body stellar system and the humans who have been bracing themselves to resist the alien attack hurtle toward the inevitable clash, is being hailed as a stunning piece of work, powered by an extraordinary artistic vision.

"His stories provide readers with a scene of the whole universe. The imagination is splendid even as it incorporates touching details," says Yao Haijun, vice editor-in-chief of Science Fiction World magazine. Human beings are as much in focus as science in Liu's work, Yao adds.

"The third book of Three Body has surpassed the first two. And it has also crushed all our previous science fiction stories into powder," says fellow writer Han Song, marveling at the scale of the story in which the author flattens solar systems and makes universes disintegrate and vanish into thin air, reappear and multiply as if he were a magician, shuffling a pack of cards.

The Three Body trilogy is a humongous work of 880,000 Chinese characters, of which the third volume, which Liu took a year to write, accounts for 360,000. "That's not much," Liu says, dismissively, seeing our jaws drop. "I write from 11 pm to 2 am every night. Sometimes I have to allow it to be published even if I'm not too happy with my work," implying, but not stating, the perennial demand of the market on his time.

He has retained his day job as a computer engineer with a State-run power plant in a remote part of Shanxi province, although he probably does not need it any more to earn a living. Rather, it helps him to stay grounded, enabling him to "gaze at the unblemished sky" as many of his co-workers do. A lot of them are not too awed by his fame as a writer, and that helps. They talk to him freely, expressing their ideas about the future of the planet.

It is the commoners, and Liu, with characteristic modesty, counts himself as one of them - like the village schoolmaster who gets embroiled in a mission to save the Earth or the window cleaner who finds himself thrown into space in Chinese Sun (2002) - who figure in his fiction and it is people like them, he insists, who he writes for.

"Science fiction is, generically, a popular form," Liu says. It is the new generation of writers, born in the 1980s, who have introduced "elite concepts" to sci-fi, he says.

Born in the late 1950s, Liu, the child of a PLA soldier-turned-mine-worker and a primary schoolteacher, grew up during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) years, trying to get his hands on anything in print.

"Science fiction was pretty much all that I got to read in those times, most of these being translations from works by foreign authors," he says.

His favorites included Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, besides some Russian authors. When he published his first short story, in 1991, it was primarily about reaching popular science to a mass audience.

"There weren't that many writers writing in this genre in Chinese at that time."

He is still a voracious reader of sci-fi fiction from abroad. In fact, he is translating a work by the American writer Paul William Anderson, but denies getting "influenced or inspired" in any way. He is driven purely, he says, "by a curiosity toward nature, and his reading of science as part of his academic (he majored in water power engineering from North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power) and professional life".

His skepticism about military research - which is essentially about inventing ways to kill people precisely and professionally - came through in the novel Ball Lightning (see sidebar).

In a world that's getting too crowded for comfort, Liu has proposed rather radical alternative survival strategies. He feels it's worth exploring the possibility of finding/creating habitable spaces beyond Earth, that it's time for the present-day Christopher Columbuses (buoyed by their enthusiastic patrons and governments) to set off on a space hunt.

"The key to a wonderful life is a fascination with something," says the protagonist's father in Liu's novel Ball Lightning, minutes before he reaches out to touch a galloping ball of lightning and is reduced to a pile of ashes.

That's a maxim Liu Cixin swears by. The man who loves risky aviation sports like hang-gliding and floating in gas-propelled balloons - although his engineer wife and 10-year-old daughter do not particularly approve of these acts of derring-do - is captivated by the idea of what lies beyond the Earth as we know it.

For him, the worlds of miners, window cleaners, wage laborers and schoolteachers also have an enduring, even mysterious, charm.