Focus

Benefits of country life back in fashion

By Wang Yan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-29 07:57

|

Large Medium Small |

|

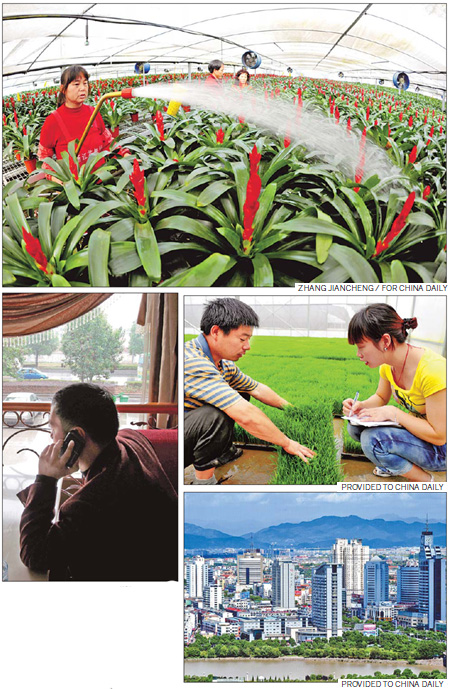

Clockwise from top: An employee of a nursery in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, waters flowers in expectation for good business during forthcoming Lunar New Year holidays; Wang Wenfeng (right) checks rice seedlings with a farmer in suburban Yiwu. After college graduation many young people in Zhejiang are choosing to go back to their villages; A bird's eye view of Yiwu, a prosperous city in East China's Zhejiang province; Ji Wengang, 29, is one of thousands of college graduates trying to swap urban hukou for their former rural status in Yiwu. The benefits of rural hukou are free house sites and yearly subsidies, while in cities the prices of housing and land continue to rise sharply. Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

As housing and land prices soar, villagers grow reluctant to surrender rural status. Wang Yan in Beijing reports.

As a child, Ji Wengang remembers most people in his village "going crazy" for the chance to become "real city folk".

It was 1992 and many farmers were spending from 4,000 yuan ($600) to as much as 20,000 yuan to swap their hukou (housing registration) from rural to urban. The nationwide frenzy was only ended by an urgent notice from the Ministry of Public Security.

Now 29, Ji is witnessing the complete opposite.

"Those who paid big money back in the 1990s must be regretting it now," said Ji at his home in Yiwu, a city in East China's Zhejiang province.

With rising house prices in urban centers, for many people, the benefits of having rural hukou - free land and yearly subsidies - now far outweigh anything cities have to offer.

New research shows that only a small fraction of villagers nationwide would be willing to swap their hukou, while many others, including Ji, are desperately trying to regain their countryside credentials.

A survey of 120,000 migrant workers in May found that just 25 percent would voluntarily give up their rural hukou.

The poll, which was conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' research center for labor and social security, included men and women aged 16 to 59 across 106 cities.

"Rural migrant workers want to work or do businesses in the cities but they don't want to transfer their registration any more," said Zhang Yi, deputy director of the research center. "The primary reason is land."

Switching to urban hukou strips residents of their rights to a "house site" - village land cleared for small-scale residential development - and annual subsidies.

More importantly, citizens with rural residency nationwide stand to receive millions of yuan in compensation from authorities when their properties are included in urbanization projects.

"As the economy develops, the value of land increases, meaning the biggest profits lie in turning agricultural land into construction sites," said He Xuefeng, director of the China Rural Governance Research Center in Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

"This can be a real benefit for (residents) in more developed rural areas."

Due to the varying rates of urbanization across China, he estimates only 20 percent of rural hukou holders can make real gains from the rising land prices right now.

"However, just because many villages are still impoverished, like in the Midwest, it doesn't mean people there would trade their land for urban hukou," said He, who predicted that the growing popularity of rural hukou will "become a national trend in the future".

Pilot for change

Like every other student in China, Ji Wengang's housing registration was transferred to his university - in his case, Southwest University in Chongqing - when he enrolled in 2000. However, as Zhejiang has been one of the fastest developing provinces, he feels the switch cost him a major windfall.

"My two brothers and I all moved out (of the village) around the same time, so my family has already lost out on several million yuan," said Ji, a marketing worker at a commodities firm.

He is now among thousands of graduates trying to make the switch back during a pilot project run by the city.

Launched in October, only students who graduated college after 1995 are eligible to apply, excluding those employed by administrative bodies, academic institutions or State-owned companies, or those involved in the Yiwu's housing reform.

Ji, who submitted his application in November, is now awaiting approval from both the city government and his designated village.

"There have been almost no regulations that allow urban to rural hukou transfers in China," said Chen Huiyu, director of Yiwu's information office. "Like other pilot areas, we have issued the regulation to meet people's demands."

Other than graduates, experts say trained teachers working in rural schools are also fueling the demand.

"We established some trial areas in October and received about 200 applications. That number increased sharply as we expanded the trial areas," added Chen.

Taizhou, a neighboring city to the southeast of Zhejiang, has been running a similar pilot project since July 2005.

According to official data, authorities helped 5,000 graduates regain rural status within the first 12 months. (Calls to the Taizhou government by China Daily this week went unanswered.)

"People in Yiwu saw how successful that was in Taizhou, so in the recent years we've continuously petitioned our city government (to do the same)," said Ji.

Status stasis

So how did urban hukou lose its luster?

For Zhang at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, it is simply a matter of economics. While land in the countryside continues to guarantee a living for millions, the cost of living in the city only continues to rise.

"The sky-high housing and rental prices alone are enough to put off migrant workers (from getting urban hukou). They're hesitant to hand over their land," he said.

Rural research director He Xuefeng agreed, adding that there is no rule against people taking the land that comes with rural hukou but living and working in the city.

"Even college graduates are struggling with life in the cities, let alone uneducated farmers and migrant workers," he said. "Policymakers should ensure that the way back to the farms and fields is not blocked to rural residents, in case they fail to settle down in cities."

Being unable to settle is a problem Zhou Shengzhe is all too familiar with.

The 28-year-old electrical engineer lost his rural hukou when he enrolled at Zhejiang Institute of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering in Hangzhou in 2002 and has struggled with accommodation costs ever since graduating.

"I pay 500-yuan a month in rent and my salary (before tax) is only 2,500 yuan," he said. "Buying a house is out of the question."

Zhou's workplace in Jinhua, Zhejiang, is just a 15-minute drive from the village where he grew up. Unfortunately for him, the city does not allow urban to rural hukou transfers.

"If I had a rural identity, I could at least get a house site, which means my wife and I would have somewhere to live," he said. "If the government can't guarantee graduates a place to live and a job like in the 1990s, why can't they let us go back to home?"

The situation can be compounded for those with "collective" status, which is when a person's hukou is in the process of transferring from rural to urban (all university students from rural areas keep this status until they buy a home or, if the option is available, transfer back home).

As these people are effectively "between hukou", this can have a major impact, especially for parents.

Gong Yuexiang, also from Jinhua, and his wife, have had collective hukou since attending further education. They now run a store at Tianyi Wholesale Market in Beijing.

"My son is already 4 years old and still has no hukou," said Gong. Without the proper registration, his child will not be eligible for the State's free compulsory education. "I don't know what we'll do when he is old enough to enter primary school in three years," he added.

The central government finally announced plans to reform China's hukou policy in June. Specifically, it aims at replacing the rural-urban system with a nationwide residential permit system.

Switching the policy from a "resource allocation function" to simply using it to measure population information "is a must", insists research director Zhang.

"Cities are under increasing pressure from the rapidly ageing population," he said. "If the country wants to (keep hitting) its annual GDP target, then cities in five years will have to rely on migrant workers to boost development."

Old ideas of "luring rural laborers to cities by giving them hukou" will no longer be effective, he explained.

"In the event of labor shortages, the key will be how successful cities are at attracting migrant workers," said Zhang. "The solution lies in setting up a fair, nationwide social welfare system that ensures freedom of migration."