Life

Saving lives at all costs

By Zhang Zixuan (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-07 08:31

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Li Jiasheng crosses the Nujiang River by sliding on a 400-meter-long zip line. Photos by Wang Wenlan / China Daily |

Once called 'barefoot doctors', China's rural doctors work in the most trying conditions to bring medical care to people living in the remotest of regions. Zhang Zixuan reports.

Just thinking about hanging on a 400-meter-long zip line, swaying 50 meters above the roaring Nujiang River is scary, admits Li Jiasheng. But the 33-year-old rural doctor in Fugong county of Nujiang Lisu autonomous prefecture, Yunnan province, knows the zip line is the fastest way reach Watuwa village, on the other bank of the Nujiang Great Canyons, for his house call.

Although he is from the Lisu ethnic group, Li, like most of the other locals, dreads it every time he has to ride the zip line.

|

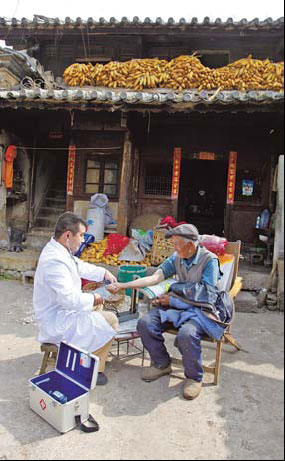

Rural doctor Yang Changlin checks the blood pressure of a farmer in Sanying village, Eyuan county, Dali Bai autonomous prefecture in Yunnan province. |

"You could become fish food as soon as you fall," says Li, who often has bruises on his legs and back from using the zip line.

Using a steel pulley and a hemp rope looped to the line, he puts his upper body through the loop and sits on it. He then hauls his medicine box over his right shoulder, steadies his trembling legs and takes a deep breath.

After pushing hard against the rock face, he is on the other side of the canyon in less than a minute.

For many villagers living in remote parts of Yunnan, a rural doctor's medicine box is all the access to healthcare they will ever have.

For the doctors themselves, it means working long hours in bad conditions and for low pay.

As the only doctor servicing 11 villages in Lumadeng township, Li has been working round-the-clock for the past eight years, ministering to more than 1,700 people.

"My work is my life," says Li, who lives next to his clinic, on call all day.

Li recalls how he once walked two days to take hepatitis B vaccine to a newborn baby in Ouludi village, on the top of a 1,800-meter-high mountain.

The mountain roads were treacherously slippery and the howl of wild beasts in the dark frightened him out of his wits.

"I cried then," says the man, almost cringing.

Unlike their counterparts in the cities, rural doctors are called upon to save lives with the most rudimentary of equipment and the most basic of knowledge acquired at "secondary medical schools", which are like vocational schools offering specialized training in basic healthcare.

To their patients, however, they are superheroes.

Once known as barefoot doctors, rural doctors are drawn from farmer families, and shoulder 40 percent of the country's basic public health services.

|

Doctor He Weizhang, of the Bai ethnic group, checks a newborn baby in Ronghua village, Lushui county, Nujiang. |

The number of rural doctors stood at 995,000, and rural clinics at 633,000, by 2009. In Yunnan, where 94 percent of the land is covered by mountains, there are 33,241 rural doctors spread over 13,375 rural clinics.

He Guangcai, 31, a rural doctor from the Bai ethnic group in Baodeng village, Luobenzhuo township, Lushui county, has more than 10,000 villagers from eight nearby villages under his care.

Fourteen years ago, after graduating from a three-year secondary medical school, the then 17-year-old took over from his father to become the family's third-generation of doctors.

He cannot recall how many pairs of shoes he has worn out going from house to house but does remember that in the past 14 years he has delivered 1,157 babies without any newborn or woman-in-labor dying.

He still cherishes what Qing Haiyu, a 19-year-old woman he saved from a difficult labor, told him: "The moment I saw you, I felt you would save me. So I entrusted myself and my baby's life to you."

Fellow villager Hu Sizhe, 36, recalls how she once accidentally took the wrong medicine and went into shock. He sucked out the medicine stuck in her throat and brought her back to life after a two-hour detoxification treatment.

"He is like my second parent," says Hu, who never fails to present He with home-made ham every year during Spring Festival.

Like most rural doctors in Yunnan, till recently, He's monthly subsidy was the same 60 yuan ($9) he got when he first started work.

His father too drew the same amount for more than 15 years.

|

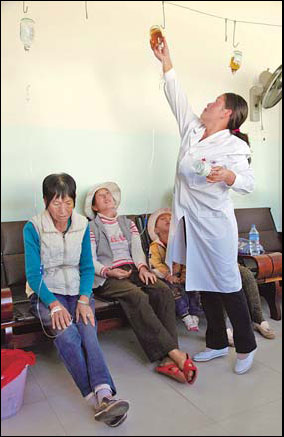

Doctor Li Yuping puts up a drip for a patient in Zhanggang village, Midu county, Dali prefecture. |

He says he and his family have never been able to afford anything expensive over the years. When he started out, there were five other rural doctors with him but they all quit.

On March 8, 2003, He's father, who had been working as a rural doctor for more than 30 years, died of high blood pressure and a stroke at 53. The family could not afford the 100,000 yuan ($15,000) for a cure at a big city hospital.

Even so, He decided to pursue the same career.

"I want to be like my father, who had won everyone's respect," says He, who made up his mind when he saw hundreds of villagers crying at his father's funeral.

In 1997 the Yunnan government specified the monthly subsidy for rural doctors in response to instructions from the Ministry of Health. Poor areas like Lumadeng and Luobenzhuo townships, where Li and He live, had to guarantee a no less than 200 yuan subsidy for each rural doctor every month.

In 2002 and 2010 the Yunnan government gave two further instructions to enforce the policy. After relying on the monthly 60 yuan for many years, He experienced the joy of a pay rise for the first time. Since January 2010, his salary has been increased to 400 yuan, including a 200 yuan subsidy for his work in family planning.

Meanwhile, the central government spent 450 million yuan constructing 11,250 rural clinics nationwide in 2010.

"I can feel the change now," Li says.

In 2008, Li's clinic was equipped with a fridge. He no longer needs to carry vaccines in an ice tray and run to villagers' homes as soon as he gets them from the county health station.

|

Lisu rural doctor Ni Douheng (left) talks with a mother who breast-feeds her newborn child in Lawu village, Fugong county, Nujiang Lisu autonomous prefecture. |

Often, by the time he reached their homes, the ice would have melted, rendering the vaccines useless.

At another rural clinic in Zhanggang village of the Dali Bai autonomous prefecture, since April 2010, Li Yuping and her colleagues have been able to weigh newborn babies with a professional infant scale. Before that they had to use a beam scale which, Li says, was "weighing babies like agricultural products".

Meanwhile, the professional skills of rural doctors is also being enhanced.

In Yunnan, the percentage of rural doctors who have attended a secondary medical school at least has risen from 13.33 percent in 2002 to 52.69 percent in 2009.

From 2005 to 2010 the central government has invested 421 million yuan on training rural doctors.

Li underwent a seven-month dentistry training co-hosted by Nujiang Health Bureau and Swedish experts in 2005. He has also participated in several short training exercises every year on first aid and Chinese herbal medicine.

Although medical and living conditions are still poor and the workload is always heavy, these rural doctors are holding on.

"The respect and moral support of our patients is what keeps us going," Li says.