Life

Fired up for the day

By Chitralekha Basu and Guo Shuhan (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-13 08:09

|

Large Medium Small |

|

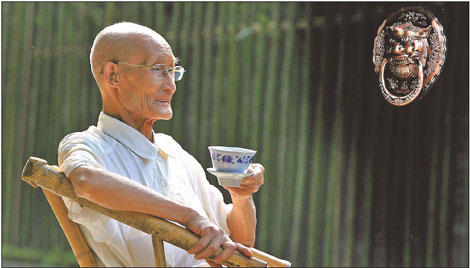

Chengdu is a city famed for its laid-back lifestyle, where people like to spend their days in parks or teahouses. Zhu Jianguo / China Photo Press |

Sichuan's damp air and overcast skies help explain this mountain-locked province's famed mind-blowing spicy cuisine. Chitralekha Basu and Guo Shuhan report.

In essence this is a love story. That's how Chengdu-native and food writer Shi Guanghua describes Sichuan cuisine, as we know it today. And like all classic romances, the union of Sichuan's native Chinese prickly ash and pepper, imported from South America around the end of the 17th century, via Europe, could be a challenge to anybody trying to sample it, especially the first-time round.

The taste-bud-tingling, gullet-numbing sensation has now become a metaphor for Sichuan cuisine - famed the world over for its sharp and furious kicks on the palate, threatening to set one's mouth on fire.

As for the people of mountain-locked Sichuan, where the air is damp and the skies overcast on most days, this fiery hotness in their food is a sure-shot turn-on, Shi says.

But that's only half the story. For the "hot" in Sichuan cuisine is not just the lethal punch that might send unaccustomed diners gasping and reaching for a jug of iced water. It can also be experienced in its array of subtly-defined, multi-layered, many-splendored varieties (see sidebar).

The tradition of adding spice to food to warm up Sichuan residents, negotiating degrees of dampness all year round, began at least two millennia ago.

|

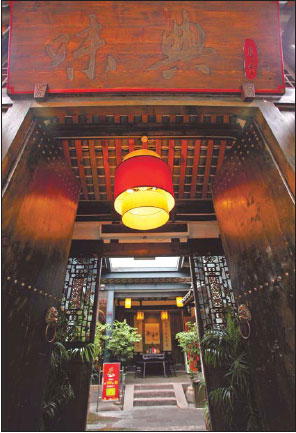

Kuanzhai Xiangzi is a popular hangout for food-lovers in Chengdu. Niu Shupei / For China Daily |

Li Shuren, who at 85 is something of a father figure to Chengdu's most-celebrated chefs and food experts, says that elements of Sichuan cuisine can be traced back to the Shang-Zhou era (c. 16th century-256 BC). The earliest evidence of spicy hot cuisine can be found during the Wei Dynasty (AD 220-265), which took a more developed form at the time of the Tang (AD 618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties, evolving even further in the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

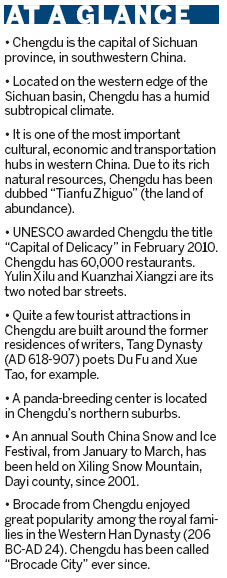

Legendary Tang Dynasty poets of Sichuan - Li Bai and Du Fu, for example - were seasoned gastronomes. The Sichuanese, as admiring of their men and women of letters as their cuisine, have named some of their native specialty dishes after them.

A dish of dried bean curd is named after the Tang Dynasty poetess Xue Tao, while her fellow writer Su Dongpo from the Song Dynasty lends his name to the braised Dongpo pork. Intellectuals like Guo Moruo have added value to Sichuan cuisine by writing about them, according to Li Shuren.

"Two thousand years ago, when pepper was unknown in Sichuan, people used ginger, garlic, mustard, cornel, locally grown vegetables chong cai and la cai to add spice," Shi says.

The entry of red-hot chili pepper toward the end of 1600s changed all that. The world of piquant flavors has since opened up for the spice-addict Sichuan residents, who believe in embracing anything that tickles their taste buds. Even the Indian curry is trying to make inroads into Sichuan kitchens, Shi says.

Sichuan cuisine has undergone a sea change, quite literally, since China's opening up in 1978. An abundance of seafood appeared after the ban on imports was lifted.

"Even domestic kitchens are using beef flown in from Australia," Shi adds.

|

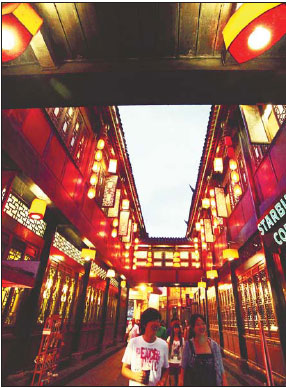

Visitors enjoy Chengdu's bustling night life in Jinli, a street known for a variety of souvenir stores and snacks. Niu Shupei / For China Daily |

"In the first years of China's economic reforms, Chengdu had about 30 decent restaurants, now there are 60,000 in a city with a population of 11 million," says Li, who presides over the Sichuan Gastronome Association. "In the past, high officials, eminent personalities and business people formed the clientele. Now, ordinary people with rising incomes like to explore the food scene as well."

Li Hongwei, 35, who is the executive chef with Shangxi restaurant on Chengdu's posh Kuanzhai Xiangzi, says chefs today "are required to keep a keener eye on quality control than before even as they enhance their professional abilities and cultural understanding of food". As clients become more aware and discerning, one has to be more cautious about "the authenticity of the ingredients used".

Li Hongwei spends lots of time reading related books and watching videos and makes it a point to look for the cultural context leading to the evolution of a dish he might be preparing in its present form.

Both Li Shuren and master chef-turned-food writer Peng Ziyu, 65, who prepared a banquet menu for former French president Jacque Chirac and former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd, believe innovation is the key for any cuisine tradition to sustain itself.

When Peng served Chirac in 2004, he toned down the spiciness of mapo tofu, having been informed of the French president's tastes. Peng was awarded the Masters of Sichuan Cuisine accolade when he shredded and fried a Chinese watermelon worth 2 yuan (30 cents) to resemble 12 chrysanthemums. "Nobody could tell what went into the making of a dish that looked so classy and sophisticated," Peng chuckles.

He is totally in favor of incorporating Western methods that change the molecular composition of foods by using chemical or physical methods.

"This method has the advantage of sustaining the nutrients, and is an effective way of coming up with substitute food for people with special requirements. A patient forbidden to have egg yolk can have a substitute made from mango, for instance," he says.

"Sichuan cuisine is the most widely-consumed among the Chinese cooking styles worldwide, with 3,000 basic dish types and 20 basic flavors. Most Chinese restaurants, the world over, serve Sichuan-style food," Shi Guanghua says. "No matter where you come from and whatever your age and gender, you will find a dish of Sichuan cuisine that matches your tastes."

A 2006 statistic shows there are some 9,000 restaurants serving Chinese cuisine in Britain, 2,200 in Holland and more than 7,000 across Germany. A program co-produced by Love Radio of Chengdu Broadcasting Station and the BBC, first aired in 2004, with the aim of introducing cuisine to a Western audience by engaging in light chitchat, and is still a favorite.

What's probably needed is a more concerted effort to further the cause of Sichuan food. There are still a few stumbling blocks between this widely admired cuisine style and it making a big splash in the international arena, feels Mai Jianling, vice-president of Sichuan Gastronome Association, which is dedicated to popularizing Sichuan cuisine across China and beyond.

While food and wine companies with substantial credentials are trying to get into the business of running Chinese restaurants abroad, their efforts are often thwarted by local regulations on food safety, the nitty-gritty of the legal procedures involved in setting up a restaurant and inadequate market research.

The Sichuan Gastronome Association, which has a tie-up with the Overseas Chinese Union, sent four chefs to Brazil and Venezuela in 2009 to help Chinese-origin residents wishing to start a restaurant business get a grasp on Sichuan cuisine.

"Besides having a dedicated organization which helps connect people wishing to take Sichuan cuisine abroad and the corporate and catering associations there, we also need a comprehensive market survey in order to form a business strategy," Mai says.

To catch on in Western cultures Sichuan cuisine also needs to achieve standardization in terms of the presentation of a particular dish. "But the chefs here want to retain their individual touch and are constantly innovating," Mai says.

Apparently, innovation is not always a blessing.

Shi Guanghua picks his top 3

You can't leave Sichuan without sampling:

Mapo tofu: "This best represents the ma la style. There are at least 5,000-odd dishes prepared from beans in Chinese cuisine and one could write a whole book on this subject."

Twice-cooked-pork (Huiguorou): "This is the best among the so-called 12 gold hairpins (adornments) of home cooking in China."

Napa cabbage in consomme: Preparing the soup involves a rather intricate procedure conducted over four or five hours. At the end of it, the cabbage opens up like a blooming lotus in the consomme.

"It's regarded as the masterpiece of Sichuan cuisine and is hardly ever cooked nowadays. The simplest of ingredients are used to cook this deluxe delicacy."

In 1963, when Shi's monthly income was 31 yuan, the dish cost 2.8 yuan. In the 1980s, it cost 88 yuan.

Just how hot does it get?

While spicy Sichuan food is often referred to by the generic term ma la (tingling spicy), here are some of the subtler variations, with examples of preparations in which one might find them.

The Chinese-English Dictionary of Sichuan Cuisine lists the following:

Hot and sour / Hot-and-sour noodle

Jiao (Chinese prickly ash) ma flavor/ Jiaoma-flavored chicken

Hot-and-spicy/ Hot-and-spicy crab

Hu la flavor/ Hu la-flavored chicken powder (this is the strongest)

Ma la / Mapo tofu (the perfect dish should combine the following properties: tingling, hot, fresh, savory, warm, tender and crisp)

Food writer Shi Guanghua adds to the variations:

Dry hot/ Sliced chicken with chili sauce

Fresh hot/ Any dish with a sprinkling of green pepper

Multi-flavored with hot as the predominant taste/ Fuqi Feipian (sliced beef and offal in chili sauce)

|

Sichuan opera masks are popular souvenirs. Jiang Xiaoming / For China Daily |

|

The bronze statue of Du Fu in the Tang Dynasty poet's former residence. Lu Xizheng / For China Daily |