Life

Finest Cuts: The emperor’s old clothes

By Wu Yiyao (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-16 08:54

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Sons traditionally inherited the secret skills of kesi weaving, but times are changing and the Wang family is breaking tradition. Yong Kai / China Daily |

|

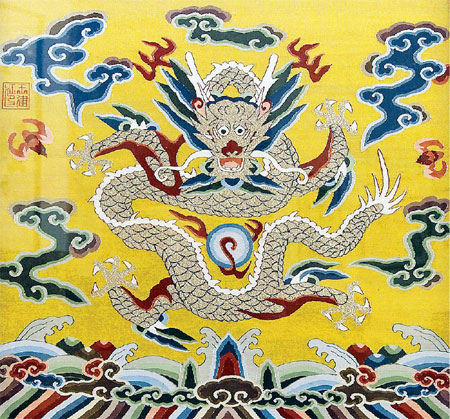

The imperial robes may have glittered in their time, but centuries of wear and tear will diminish their glory. Provided to China Daily |

When it comes to the intricate imperial robes of ancient royalty, only one family can do a makeover. Wu Yiyao visits a clan of specialists in Suzhou that has been doing that for six generations, and counting.

Even the emperor's best clothes are subjected to wear and tear, especially after hundreds of years. So it did not surprise Wang Jialiang when officials from Beijing's Palace Museum turned up at the doorsteps of his suburban Suzhou workshop bearing the imperial jacket of the Emperor Qianlong (1735-1796). They wanted repairs done for the centuries-old robe, and Wang and his family of kesi craftsmen were the only people who can do the job. Kesi is an intricate weaving process and the word literally means "carving with silk?

"We are among the few who can do it right, so we are obliged to do the job well," said Wang, 70, the fifth generation descendent of a family who specialized in weaving kesi imperial suits, using an ancient art that dates back thousands of years to the Han Dynasty (206 to 220 BC).

Another name for this almost lost art of weaving is "cut silk", which refers to the raised pattern the weave produces, almost like an appliqu.

It lost favor through the ages and was revived during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The Manchurian Qing rulers, with their love for Han arts and culture, made kesi popular again, and Suzhou became the center for kesi weavers.

It was during this revival that Wang Jinting, the current master craftsman's great-great-grandfather, was appointed to the Royal Court as its supplier of kesi robes for the royal family and top court officials.

The emperor's dragon robes were the ultimate symbol of power, its five-clawed dragons woven in intricate gold, silver and silk, and worn at court in dazzling display. These days, the robes are more likely protected in dimly lit museum vaults and occasionally displayed in light, heat and humidity-controlled cases.

Even the occasional kesi robes still in circulation outside of the museums are priceless - almost. At an auction in 2008, a kesi quilt with Buddhist scripts from the Qianlong period sold for 65 million yuan ($9.9 million).

Even when new and not inflated by the antiquity of age, kesi works are extremely expensive and have always been an exclusive luxury for royalty and aristocracy. Part of their value is in the time it takes to produce one perfect piece of tapestry, sometimes a whole year.

There is also no room for mistake. Because it is woven, it cannot be undone, and a mistake may mean that the craftsman starts all over again, from scratch.

For Wang, handling fragile national treasures is just part of everyday work. The specialized weaving is what his family is all about. They are the rare ones still practicing the craft, proud of the heritage and very protective of it.

With eight looms inherited from his father, Wang and four of his descendents worked eight hours every day for 10 months to complete the repair of Qianlong's robe, a job that is even more tedious than making a new one.

"A normal kesi piece uses 40 horizontal threads on one centimeter of warp, but the imperial robes use 100 threads on the weft, so we have to pull the new silk threads very taut while making sure the original threads do not break," says Wang Jianjiang, Wang's eldest son, and the next generation kesi master.

And in order to make the repair invisible, the new silk treads must be aged before they are attached to the original, which means extra effort and an extra process.

"Scholars with the Palace Museum were impressed with our work, and they sent an expert on antique restoration to our studio to learn the art of kesi after we completed the project," says Wang.

The family also spent three years working on a replica of the imperial robes of the Ming Emperor Wanli (1563-1620) for the Capital Museum.

The original had been worn down by the years and was not suitable for display. The replica was to showcase the Ming-style of kesi weaving exactly as the original was intended to do.

It took 3,000 meters of peacock-feather fabric, three kilograms of silk threads and 10 spools of gold threads imported from Japan to complete the job.

Now, the family's current project is to create a replica of another robe of the Emperor Qianlong's.

Being the custodian of a dying art presents a mixed platter of blessings and worries.

"People say the art of kesi is dying, and I am afraid no one will do the job in the future as few young people want to learn the craft," says Wang Jianjiang. "For the young, it is really tedious work, and it doesn't make enough money."

There are also the limits of the line of heritage. Traditionally, master craftsmen only pass down their skills through the male heirs, usually the firstborns, so the secrets of the craft stay within the family. Wang Jialiang decided to break with tradition, and he has passed on his skills to all his daughters and daughters-in-law to keep the craft from disappearing.

Xu Peiying, wife of his second son Wang Changjiang, is one of his female disciples.

She started learning the art at the age of 14 and has been working the loom for three decades. An experienced kesi artist now, Xu was part of the team that repaired the imperial robes, but she has paid a price for the years of intricate work with failing eyesight.

Xu is nostalgic for what she called the golden age of kesi about 20 years ago, when the demand for kesi kimono sashes, or obi, was at its height. An experienced kesi craftsman could earn 10,000 yuan a year, which was a large sum of money then.

"We could trade a Japanese car with a completed kesi kimono sash," Wang Changjiang says.

However, that bubble broke when the financial crisis swept Asia and the demand atrophied, almost overnight.

With that came inflation and the price of silk threads more than doubled from 210,000 yuan per ton to 580,000 yuan per ton. The rising cost proved too much for customers.

Workmanship is also expensive.

"Some say we charge too much when they find out that a handkerchief-sized piece of work cost at least 5,000 yuan, but it is not easy money," says Wang Changjiang.

His father agrees. He spent half a year working on a patterned quilt with cranes and priced it at 20,000 yuan.

Even at these prices, it is hard to make ends meets where there are no commissions.

Things may change for the better in future, especially since the art of kesi has been listed as a national intangible cultural heritage since 2009.

The family's three-room studio, together with the cultural heritage protection research center of the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, is part of a kesi craft protection and research base set up in 2010. Here, they will research techniques from past dynasties and try to restore some extremely challenging techniques that have not been attempted before.

The Wang family also has a shop in Fengqiao, a scenic spot in Suzhou, to try to develop a business outlet for their art.

Finally, another generation of kesi craftsmen is already being groomed. The 21-year-old daughter of Wang Changjiang and Xu Peiying has been learning the craft for the last three years.

"Now I know my daughter will carry on the family business, but I am still hazy about what will happen after she retires," says Wang Changjiang.

For this family of artists, the continuity of the craft is their main worry, and they are challenged by the march of time, which none can stop.