Life

A long way to go

By Gao Qihui (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-17 08:04

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Millions of migrant workers rely on the nation's slow trains to return to families for the Spring Festival. But will these trains survive the rapid upgrading of the rail network? Gao Qihui reports.

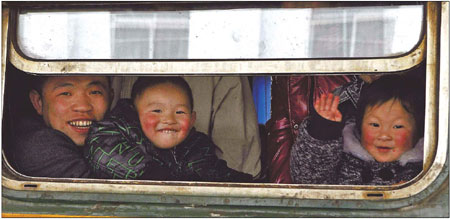

With the Spring Festival nearing, Yang Yongfen joined millions of others across the nation to return home, in what is seen as the world's biggest annual human migration, to usher in the New Year. Yang spend at least 30 hours to travel 1,946 km from Hangzhou, capital of East China's Zhejiang province, to Anshun of Guizhou province in Southwest China, by slow train.

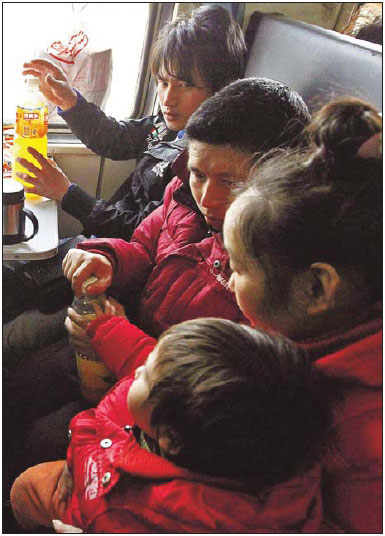

Yang and her 7-year-old son, along with her younger sister and her brother's little daughter, crammed into a 1-square-meter space at the entrance to the carriage, sharing two small foldable travel stools between them.

Yang took the train on Dec 31, 2010, 20 days before the peak travel season, but still found it difficult to find space inside the carriage.

Even as the train started moving, several passengers carrying big suitcases high above their heads, tried to snake through the crowd squashed up against the side of the carriage, looking for any space to put down their luggage.

Almost all the passengers spoke in the dialects popular in Southwest China, including Sichuan and Guizhou provinces, the source of the nation's millions of migrant workers.

For these low-income earners, the cost of travel is an overriding consideration. Yang, the plainly dressed 37-year-old mother, who works as a migrant worker in Hangzhou, chose the slow train No 1271, for it offered the cheapest way to get to her hometown, with a standing-room-only ticket costing only 107 yuan ($16.24).

Yang would have had to pay an additional 210 yuan for berths but "we wanted to save that money", she says.

The fares on China's slow trains, marked by their distinct green color, are the lowest but lack heating and take longer to cover the same distance as others.

"I don't mind the time it takes," said Jiang Bo, a 23-year-old man who sat on the train for at least 44 hours before arriving at his home in Sichuan's Zigong city.

He would have had to pay about 200 yuan more for a fast train and a transfer to a bus to get home. He said that was not an economical choice, pointing out his garment factory job earns him less than 100 yuan a day. Jiang Long, a 21-year-old with barely enough room to stand, said cheerfully: "Last year when I took this train, it was more crowded. I couldn't even bend. It is much better today."

Slow trains are so-called not because they run slowly but because they take longer to reach their destination. They have to make more stops - at small cities and towns that fast trains do not pass or pass through without stopping.

Without the slow train, these passengers would have to first travel to the big cities and then take the fast train, a time-consuming and costly option.

But with China upgrading its railway network, these slow trains are slowly being phased out.

Seven such trains starting from Beijing were cancelled in July, 2010.

A report in the Beijing Times on June 29, 2010, quoted the Deputy Director General of Beijing Railway Bureau Liu Ruiyang as saying that from July 1, 2010, all slow trains entering Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou of Guangdong province would be replaced.

According to the latest railway map, the No 1271 has already been replaced by the faster and better K1271.

China's high-speed railway network now stretches 8,358 km, and will be extended by nearly 5,000 km more in 2011.

At present, there are nearly 1,200 China Railway High-speed trains - with speeds higher than 200 km/h - running on the nation's railways every day.

But the upgrade also means higher fares. The priciest tickets on a high-speed train, that began operating on Jan 11 between Shanghai and Chengdu, will cost as much as 2,330 yuan ($353.64), with the cheapest going for 501 yuan.

Reacting with incredulity at the fare, Luo Yinguo, a 53-year-old working in a leather factory in Wenzhou city of Zhejiang province, asks: "Is that a five-star train?"

Luo says he dare not think about it, as the priciest ticket equals his monthly earnings.

But faster railway transportation "is a national strategy, aimed at meeting the demands of economic and social development", says Xia Xueluan, sociology professor at Peking University.

According to Ji Jialun at Beijing Jiaotong University, "China's development of high-speed railways will leave more room on the track for freight trains.

"Currently, the railways' freight transportation capacity meets only 35 percent of national demand," Ji says.

"To allow one passenger train to run, we have to cancel two freight trains," he says.

At present all rail lines, except the newly built high-speed-train-only lines, are open to both passenger and freight trains, which restricts the development of freight transportation.

The phasing-out of slow passenger trains will leave more room for freight trains, Ji says.

Professor Hu Xingdou, at the Beijing Institute of Technology, feels both freight and passenger transportation need to be expanded. Hu told China Daily that the construction of the rail network in mid-western China is already insufficient to meet demand.

The problem will worsen if more passenger trains are taken off the tracks in this region, he adds.

In fact, it is this region that is home to most of China's low-income groups and the one that generates the most demand for slow trains.

Some experts have suggested the use of buses over trains.

But Luo Yinguo, the leather factory worker in Wenzhou, dismisses this saying, "It is too expensive".

A coach bus to his home in Zhaotong city, Yunnan province, will cost more than 350 yuan.

And during peak travel periods, such as the Spring Festival holiday, prices could rise to as much as 800 yuan, according to Luo. In contrast, a slow train such as the old No 1271, costs less than 200 yuan.

Even the hard-seat ticket on its replacement, the K1271, is not likely to surpass 400 yuan.

Bus travel is also seen as less safe than travel by train, Luo says.

However, Xia of Peking University believes that as living standards rise, more people will gradually accept the price of fast high-speed trains.

"It is just a matter of time," he says.

But besides cost, another concern for Luo is whether the new train will still stop at Zhaotong.

On the line between Wuhan, in Central China's Hubei province, and Guangzhou of South China's Guangdong province, the normal fast train K769 stops at 26 stations but the new high-speed train G1021 has only four stops.

The many county-level stations is one reason Hu at the Beijing Institute of Technology cites for keeping the slow trains.

Agreeing with him, Ji, of Beijing Jiaotong University, says some short-distance branch lines, without much freight traffic, should be kept open for the slow trains.

Meanwhile, despite the expansion of the high-speed rail network, migrant workers can still take their preferred cheaper slow trains.

During the Spring Festival travel rush, the Ministry of Railways always adds more train services in the main migrant labor hubs such as Sichuan, Henan and Anhui provinces.

For the 2011 Spring Festival travel season, for example, 123 more trains will be put into service by Beijing Railway Bureau, according to its transport plan released on Jan 5.