Focus

Injured laborers unaware of free rehab amid compensation fears

By Li Li (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-25 07:51

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Migrant worker Dai Zhengsheng displays the hand he injured on a Beijing construction site in November in this photo taken last week. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

Limited resources and lack of promotion blamed for underused centers as migrant workers left unattended. Li Li in Beijing reports.

Dai Zhengsheng lost his left forefinger in November when he slipped using an electric motor saw at a Beijing construction site.

"I used to lay the neatest brick floors," said the 56-year-old. "Now, I can barely put my own clothes on."

Like other migrant laborers who suffer injuries on the job, Dai is eligible for the State's free rehabilitation program. Yet, he rejected the offer for fear it will affect the process of getting compensation from his employer.

"I need money," said the bricklayer, whose wife and 1-year-old daughter live in Henan province. "I can't wait any longer. Spring Festival is coming and... I plan to go home and start an animal farm."

Although Dai refused rehab treatment, experts say the majority of people - particularly migrant workers - do not even know it is available.

In fact, so few have taken up the offer that the Industrial Injury Insurance Fund, which was set up in 2004 and can be used for rehab services, had a surplus of 44 billion yuan ($6.68 billion) as of September 2010.

China has 338 medical clinics that offer rehabilitation, including 35 experimental industrial injury centers certified by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. The network is made up of about 50,000 beds and 40,000 health professionals, according to 2010 figures from the Ministry of Health.

This means the system can provide two-month treatments to 300,000 people at any one time, said Tang Dan, president of Guangdong province's Work Injury Rehabilitation Center in Guangzhou.

However, with 1 million laborers suffering new injuries every year and many others affected by recurring ailments, Tang estimates more than 400,000 people are in need of rehab services. "The country's demand for industrial injury rehab greatly surpasses supply, but few are actually receiving it," he added.

Results of a survey published this month show almost all 73 laborers interviewed in Beijing suffered "minor injuries" that could be improved by rehabilitation. "None received any because they didn't know about it," said Shi Fumao, director of the Zhicheng Legal Support Center for Migrant Workers, which carried out the poll.

Back on two feet

Delivery driver Ban Jiyuan suffered fractures to his pelvis and thighs in a traffic accident on his way to work in Guangzhou last August. He feared he would never walk again.

"When I returned home from the hospital after the surgery, I didn't know how to walk properly," said the 38-year-old.

After filing a report on his injuries, his employers sent him to Guangdong's Work Injury Rehabilitation Center, where after a month of professional physiotherapy he was able to walk with the use of crutches. "The doctors told me I should be able to walk unaided in two to three months," he said.

On top of the physical help, Ban, who hails from Guizhou province, has also been able to learn computer skills to help boost his job prospects. (His boss has offered him work after he is discharged.)

Opened in 2001, the Guangzhou center is the first and largest facility of its kind on the Chinese mainland. It can treat up to 200 workers a time and offers a range of services, from physiotherapy and occupational therapy to speech therapy and psychological counseling.

Guangdong's authorities are leading the way in industrial injury rehabilitation. Unlike in other provinces, health professionals from the center regularly visit hospitals to evaluate potential claimants and actively promote rehabilitation services. (Some admitted that hospitals can be uncooperative as they "see us as thieves stealing their business".)

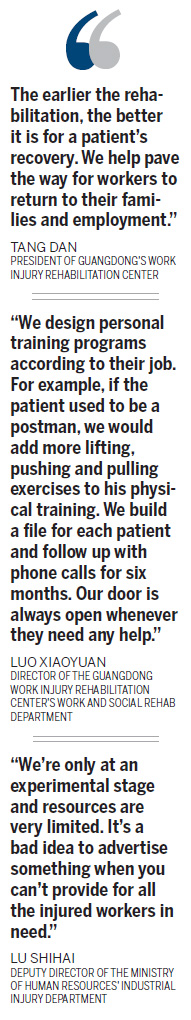

"Early rehabilitation is better for a patient's recovery," said Tang, president of the center. "We help pave the way for workers to return to their families and employment."

With 43 work stations built to simulate environments for various professions, such as drivers, waiters, electricians and cooks, patients are given practical training to cope with their injuries on a daily basis.

"We design training programs according to jobs," said Luo Xiaoyuan, director of work and social rehab at the center. "For example, if the patient is a postman, we will add more lifting, pushing and pulling exercises to his training."

Workers often return to companies for trials, with regular evaluations to ensure they are progressing well, while the center will also carry out home modifications for patients with long-term mobility problems.

"We build a file for each patient and follow up with phone calls for six months," said Luo. "Our door is always open whenever they need any help."

Roughly 78 percent of the clinic's patients have returned to work in the past three years. To replicate this success, Tang's staff members now provide technical support to bases in other cities and provinces.

"Every year we receive different experts from Guangdong to instruct our work," said rehab executive Zhan Lifang at Boai Hospital, the only dedicated industrial injury rehab facility in Hunan province. "In 2009, we had a re-employment rate of more than 50 percent."

Poor coverage

Zhicheng Legal Support Center, founded in 2009, has 25 professionals in 31 branches nationwide offering free advice to migrant workers (funds come from China Legal Aid Foundation). Lawyers here mainly deal with pay disputes, which take about five to six months, and injury claims that often last more than a year.

"So far, none of my migrant worker clients have demanded anything related to rehabilitation," said attorney Wang Fang. "Their focus is always on compensation."

Rehabilitation is not compulsory under either the Industrial Injury Insurance Regulation or any labor laws, nor do local governments advertise the services. Therefore, few migrant workers even know about it.

Lu Shihai, deputy director of the Ministry of Human Resources' industrial injury department, said the lack of promotion is due to the fact existing facilities would not cope with potential demand. "We're only at an experimental stage and resources are very limited," he said. "It's a bad idea to advertise something when you can't provide for all the injured workers in need."

Judging by the reaction from migrant workers China Daily talked to, there is unlikely to be a rush for rehabilitation services even if it is advertised. Like Dai, who lost a thumb, many of them believe that going into rehab will delay or even reduce the amount of compensation they receive from employers.

Evaluations to determine the severity of an industrial injury are done after treatment and workers "are afraid they will get less if they recover too well", said Tang in Guangzhou.

Yu Youcheng, 40, said anyone who chooses money over health is short sighted, yet even he refused rehab when he fractured his fingers in 2009.

His employer - a machine factory in Beijing - had not paid for his industrial injury insurance and "they were also holding back a few months' salary", said the worker from Sichuan province. "I wanted to try rehabilitation but I didn't want to upset my boss by asking for (rehab and compensation)."

As with most labor disputes, migrant workers are in an extremely weak position, not least because they have little knowledge about the law.

When Fu Jiarong injured his back in a Chongqing mine accident, his boss spent a year paying his hospital bills. Then, suddenly, he disappeared. The 40-year-old only realized he had been cheated when he contacted an attorney and was told he had missed the deadline for declaring an industrial injury.

"The employer deliberately took advantage," said Li Kezhong, a lawyer who later represented Fu. "The law promises a lot of rights to migrant workers but few enjoy them."

Changing course

An update to the Industrial Injury Insurance Regulation that came into effect on Jan 1 this year has prompted some authorities to be more proactive about rehabilitation. In Shanghai, for example, bureaus responsible for social security, health and commodity pricing joined forces to make its services more efficient.

However, Beijing attorney Shi, who is also secretary-general of the All-China Lawyers' Association's public welfare law committee, said he feels the latest move will do "little" to get more injured workers into rehab.

For a start, the regulation was released by the State Council, the country's cabinet, and not by the National People's Congress, the top legislative body. From a legal point of view, said Shi, this makes it easier for employers to ignore.

Under the rules, companies should pay industrial injury insurance for every employee. Yet, official statistics show just 24 percent of migrant workers are covered, meaning bosses are responsible for any expenses incurred as a result of a work-related accident. It is a responsibility many attempt to shirk.

"About 97 percent of cases we've dealt with involve small and private enterprises who are incorporative and irresponsible," said Shi. "Most enterprises don't even want to pay the basic insurance and compensation, let alone rehabilitation fees."

Carpenter Li Pingjun, 39, worked a year for a Beijing decoration company in 2008 but never once met a manager. "It was always the labor contractor who dealt with us," he said. The first time he visited the company's office was after he broke his left hand in an accident. They told him to go away "as they didn't know me".

On the plus side, the updated regulation clearly states that the Industrial Injury Insurance Fund can be used for rehabilitation services. So far, Guangdong is the only province tapping this resource.

Funding is one reason why the rehab facility at the Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital in Liaoning province is yet to receive one industrial injury patient since it opened last month. "Without clear financial grounds, we can't receive workers," said public relations officer Zhao Lubing.

Lu at the labor ministry agreed that communication between the central government and local commodity pricing bureaus on industrial injuries needs improvement.

"One day, rehabilitation will become a forceful law," he said. "China has just started its work on industrial injury rehabilitation (the first regulation was in 2004), and the current focus is still compensation. Rehabilitation is our next direction."

|

A patient undergoes physiotherapy treatment at the Work Injury Rehabilitation Center in Guangzhou, Guangdong province. The center was the first of its kind on the Chinese mainland and can treat 200 patients at a time. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

A patient suffering from facial burns receives treatment from an experienced medic at the rehab center in Guangzhou. |