The uncomfortable side of tradition

Updated: 2014-07-07 07:37

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

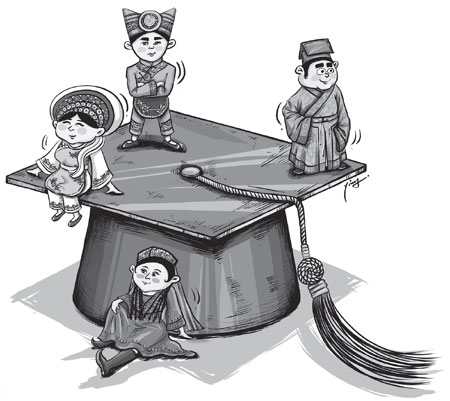

Clothes make the man and preserve tradition as well. When we use clothing to connect to the past, it is important not to let it divide us in the present.

A recent graduation ceremony made news not because of who made the speeches or what was said, but because of what everyone present wore.

The event at Jiangsu Normal University drew the nation's attention when photos surfaced online of the graduates, their teachers and even invited guests, including officials from the Ministry of Education, donning the traditional garb known as the Hanfu.

My first impression was that the Hanfu, which literally means Han clothing, bears a vague resemblance to the traditional Western graduation outfit, with its black gown and square academic bonnet.

I'm sure most Westerners would have viewed it as a Chinese variation of Western style.

But the Hanfu dates back a couple of thousand years. The "Han" in Hanfu refers to the Han people, the largest ethnic group in China, which accounts for around 92 percent of the country's population, and some 19 percent of the entire global population.

What the Han people wear today is not very different from clothing styles in most other parts of the world.

We tend to put on a Western-style suit on formal occasions.

A grassroots movement to revive the Hanfu, active in certain quarters, is an effort to assert Han people's ethnic identity.

So why can't we dress like our ancestors for weddings and funerals, and graduation ceremonies for that matter.

The envy is more poignant when you look at China's other ethnic groups and their colorful clothing, constantly on display in television galas.

I'm a Han but I've never worn Hanfu. I don't even have any, nor do any of my family members.

But I can totally understand the pride and the urgency of some of my fellow Han people who have jumped onto the Hanfu revival bandwagon.

Although the Hanfu is generally not as elaborate as most of the formal wear of our other ethnic groups, it is part of our legacy and it is an honorable thing to preserve it, especially in this age of globalization, when people in every corner of the world move in the same sartorial direction.

But as with any movement, any change to conformity, no matter how well-intentioned, inevitablely throws up different opinions.

What if one of the graduates is not a Han and refuses to be dressed as one.

Do they have the right to non-conformity? Should they be encouraged to wear the robes of their own ethnicity.

And what if there are members of different ethnicities in the student body? Would they stand out in a sea of black gowns, and how would that make them feel?

What started as a subtle resistance against global compliance could inadvertently spark a scintilla of racial discomfort.

I'm sure nobody in the revive-Hanfu movement has any intention of discriminating against our compatriots of other ethnicities. But as a majority we sometimes forget that traditions of the Han people may not be accepted in all parts of China.

I hate to call it "racial insensitivity" as it does not imply any malice or bigotry, but it could develop into a form of racial ignorance.

The irony is that the discontinued use of the Hanfu was imposed upon the Han people when the Manchus started to rule China in 1644 and forced their own ethnic clothing and even hair styles on the Chinese majority.

When the Qing Dynasty was toppled in 1911, Western influences flooded in, leaving little room for reverting to the old way of Han clothing.

The elegant women's dress known as qipao, or cheongsam, which Chinese women sometimes wear as a national version of the evening gown, was an invention of the Manchus.

For those bent on restoring the former glory of Han culture, it is all the more urgent to have something that is quintessentially Han for grand occasions.

If you study Chinese history, you'll find that there were times of ethnic harmony and times of ethnic discord, which is nothing unusual.

Just as the Qing Dynasty forced its sartorial taste onto the Han people, the Han had also coerced some ethnic minorities to abandon their own formal wear or informal wear during draconian periods of rule.

Thankfully we are now in an age of tolerance and even appreciation of other cultures.

The constant changes in fashion probably have an impact on such attitudes as people are exposed to diverse styles.

In this atmosphere, respect for old traditions comes to be appreciated as vintage chic if not as strictly abiding by the bygone ways of life.

Sometimes I wonder whether many in the revival movement are in it for the chic, rather than the heritage.

All is well if people take care not to equate the Hanfu with the clothing of the entire country and not to belittle clothing choices of other ethnicities, or frown upon those Han people who do not want to join in.

In the eras of limited mobility, China's ethnic minorities used to live in remote provinces outside the so-called Central Plains, and there was little mingling.

But nowadays when you say "Let's all don a Hanfu" you may have colleagues or schoolmates who look and act every bit like you do, but are not of the Han majority.

This will happen more and more often as our economy further helps our population to move around the country.

I didn't give much thought to lyrics of patriotic songs that rejoice in our having "yellow skin and black eyes and black hair" until I heard officials in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region had complained about it.

Some of our ethnic minorities do not look like that, and singing these songs in that area will make them feel they are being left out.

We often call ourselves "descendents of the Yan and Huang emperors", using the phrase as a catch-all for the Chinese nation.

But when I took my first trip to Guizhou, a mountainous province in southern China with many ethnic groups, I learned that locals call themselves "descendents of Chiyou", a half-mythical tribal leader of the ancient Nine Li tribe.

The history books tell us that Chiyou was defeated and driven into the mountains by the better-known Yan and Huang.

What would they feel when we proudly claim to be the offsprings of the winning team when our brethren came from the side that lost.

This kind of complication probably never dawns on most Han people simply because we rarely come into physical contact with those with a different origin story.

It may sound trivial to discuss such matters in the vast Han area, but if we assume the stand of someone who does not share our physical features, clothing style or gastronomical habits, we may understand that too much emphasis on such things can not only set ourselves apart, but also alienate others, albeit inadvertently.

After all, we are all part of the big Chinese family, and our regional and ethnic cultures should serve to influence and enrich each other.

We should cherish our traditions, including the different ways of doing things down in our small villages, but we should also realize that we have more in common than not.

We should never let our differences be stumbling blocks in our communication.

As for the future of the Hanfu, I'm afraid it will be consigned to a visible but not accessible place, a mental pantheon, so to speak.

This means you'll see highly publicized photos of people wearing it but you'll count yourself lucky to bump into someone actually wearing it in real life.

I happen to have a few friends from other ethnicities. When I asked them how often they don their colorful outfits, I expected an answer like "weddings and funerals".

But they replied: "I don't even have something like that, let alone wear it."

So, what did they wear at their own weddings? "A suit" was the most frequent answer.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Wang Xiaoying / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 07/07/2014 page8)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US south benefitting from China investment

Talks may help US soy exports

Product placement deal transforms into dispute

China approves Lenovo, IBM $2.3b server deal

Meet the new breed of migrant workers

NetJets awaits green light to start China operations

Unleashing the power of innovation

Beijing, Berlin getting closer despite distance

US Weekly

|

|