Organic labeling can be food for thought

Updated: 2011-12-29 07:50

By Wu Wencong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Wang Xiaoying / China Daily |

|

People taste tomato and cucumber at the seventh China International Expo of Organic Food, held last month at the World Trade Center in Beijing. Although many vegetables sold at markets are labeled as organic, few have been certified. Chen Xiaogen / for China Daily |

Recipe for confusion as status is hard to define and controversial, Wu Wencong reports in Beijing.

The Beijing Organic Farmers Fair is reaping a harvest of popularity. Followers of its micro blog at sina.com grew to almost 22,000 in less than a year. The fair, held monthly last year, is now a weekly attraction.

Moreover, the location has shifted from the suburban Changping district to centers such as the capital's swanky Sanlitun area.

There is just one problem. Despite the fair bearing an "organic" stamp, few of the farmers participating have actually received any certification confirming organic status.

"How can you claim your products are organic when you don't have the certificate?" asked Sun Dewei, who runs a small farm in Shunyi district.

Sun said his farm operates in a way that's as close as possible to, but is still not completely, organic. "Whether it (the certificate) really works or not, it is the only legal way in China to carry the organic label," he said.

A number of food safety cases have erupted recently. As a result, consumers, especially the middle class who can afford and are willing to pay higher prices for healthier food, are enthusiastically chasing organic products because they believe them to be safer and healthier.

However, insiders and experts say that being safe is simply the bottom line for organic food. In China, not only is the term "organic" being abused, but the part it can play in promoting food security has also been overestimated as a result of the high-end nature of the food and the disorganized nature of the industry.

Abuse of concept

Sun refers to his farm as "continuous" rather than "organic", saying that "organic" should be used sparingly and only then with authorization. "They (the farmers at the fair) think the certification system for organic food is lame, yet they themselves are using the term to lure consumers, who lack basic knowledge about organic food."

Sun, who has been running his farm for 10 years, said "organic food" means much more than just produce that has been grown without chemical fertilizers and pesticides. He said there are other technical criteria, such as the use of seeds without a chemical coating to help growth.

Another is an isolation belt of a certain width, within which crops such as corn are planted to prevent contamination from outside chemicals but which will be abandoned later, not sold.

"This criterion alone shuts the door on the term 'organic' for many small farms around Beijing," Sun said. "The land they have is already limited enough for planting produce, so how can they shoulder the cost of growing hectares of crops that they can't sell later?"

He suggested that fairs such as the one in Beijing could use labels such as "safe products" or "natural", instead of "organic". Meanwhile, there have been complaints about products sold at the fair that are not fertilizer-free.

Luzhimeng, which translates to Green Union, is a small shop in Beijing's Changping district that was among the first retailers to join the Beijing Organic Farmers' Market when it started last year. In October the owner decided to quit.

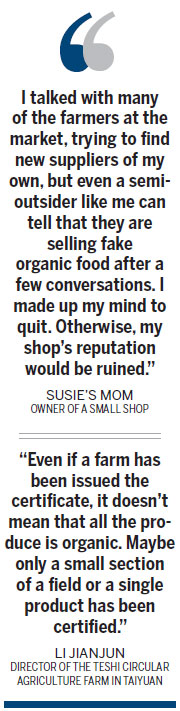

"I talked with many of the farmers at the market, trying to find new suppliers of my own, but even a semi-outsider like me can tell that they are selling fake organic food after a few conversations," said the owner, a 36-year-old former housewife who prefers to be called Susie's mom. "So I made up my mind to quit. Otherwise, my shop's reputation would be ruined."

The shop sells safe and organic food, mainly in its own neighborhood, and was launched by six mothers who wanted their children to have safe food.

Certificate of what?

One of the organizers of the fair is Chang Tianle, a project officer from the Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy. She said they never claimed to be selling organic food there, that the term is used only to describe how the farmers adhere to organic standards and core ideas.

The fair is very careful in selecting farms to participate, she said. The food not only has to be free from chemical fertilizers, but also must be produced locally. "The certification bodies only conduct two supervisory visits every year," she said, so she doesn't place much stock in their evaluation.

As for complaints on the market's micro blog, Chang said the fair treats every customer complaint seriously and carefully: "So far, no suppliers have been discovered cheating."

As both a vendor and a consumer, Susie's mom also looks down her nose at the certificate. "I trust my own eyes more."

Luzhimeng has about 10 suppliers. Some are authorized farms, but most are not. Every week, the shop buys about 400 kg of vegetables, selling them at 16 yuan ($2.50) a kilogram to its 100 or so members.

There are some "open secrets" in the industry about which farms fake organic food that Susie's mom learned after becoming friends with a number of insiders. "Some non-governmental organizations also helped me to distinguish the real organic produce from the fake," she said. "I value the trust that exists between the suppliers and me more than the certificate."

Speaking at the first international summit related to the organic industry, Li Jianjun, director of the Teshi Circular Agriculture Farm in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, said the process lacks efficient supervision. "Even if a farm has been issued the certificate, it doesn't mean that all the produce is organic," Li said. "Maybe only a small section of a field or a single product has been certified."

Some farmers mix organic products with non-organic to ensure their income through greater yields, Li said. "Currently, we can only count on their consciences."

New standards

A senior staff member from one of China's 23 official certification bodies, who spoke on condition of anonymity, disclosed that a new national standard will be unveiled in March to ease the chaos. The standard will include four important changes from the original, in 2005. This staff member has been working in organic food certification for about eight years.

He said the first two changes will concern the transition period, akin to probation, when a farm applies for the certification of land. It lasts for 24 or 36 months, depending on the crops grown there, and farms must begin following organic practices three or four months before the transition period.

Under the current standard, as soon as farms enter the transition, they can obtain yellow certification, indicating their products are moving toward organic. Green certification is granted only if the farm passes probation.

"The problem with this stage is that, under the current standard, a farm can get a transition period certificate, even if it only stopped applying chemicals on the crops three or four months earlier," the senior staff member said.

Under revised procedures, no certificates will be issued in the first 12 months of transition. "That is to say, the farm will have to stop using chemicals for at least 15 months before it can receive a yellow certificate," he said.

Also, farmers will not be allowed to label their products "organic transition food", which has been used to denote food that was better than ordinary but not as good as organic. The staff member also said the new regulations will set the acceptable level of pesticide residue at zero. The current standard allows "one-20th of that found in ordinary food".

In addition, serial numbers will be introduced for each product. Consumers will be able to check with the body that authorized the product on the website of China's Certification and Accreditation Administration.

'The price of faking'

The staff member said the administration of organic food has been getting tighter since a number of problems arose in 2003. Typical problems then, he said, were the sale of different certificates in bundles and charging fees for one certificate several years in advance, even though there's no guarantee the farm could pass the test in those years.

Issuing certificates is the only method for the bodies to gain income, he said, so there are incentives to issue them outside the rules. "I can't say that the new standard will solve all the problems with the certification of organic food right now," he said, "but the price of faking will be much higher."

He acknowledged that many customers are ignoring national certificates and relying on personal relationships with small farms so they can distinguish real organic food from fake.

"Unauthorized small farms are actually a good thing in this industry," he said. "Their products may not be 100 percent organic, but at least they are free of chemicals and pesticides."

Ways out

Food safety issues have driven many large State-owned enterprises into the organic food industry. Xia Hongzhi, general manager of Beijing Fuhaihuakang Organic Food, said China Minsheng Banking and China Petroleum & Chemical are among his clients.

"They rent a piece of land from our farm, and we are responsible for the growing and quality control," Xia said. "They can send their people to monitor us during the entire process."

Sun, the small farmer in Shunyi, said he thinks that both government and customers pay too much attention to the industry. "Organic is high-end, even in Western countries," he said. "Counting on it to solve the food issues of hundreds of millions of people is unrealistic."

Sun's claims were supported by the senior certification staffer. "Unlike domestic (Chinese) consumers, Western buyers don't go after organic food for safety, because most of the food they can get is safe anyway. They are buying it with the intention of contributing to environmental protection, which is also the original intention of the term."

He said organic food is simply the bottom line at the technical level. The core ideas - sustainable land use and reduced use of outside energy - are the important factors.

Sun thinks there is no reason to be afraid of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, as long as they are used within prescribed limits. Leaving land fallow on a regular basis, allowing it to recover from use, is also crucial.

"If ordinary vegetables, which occupy most of the market share, could be guaranteed as safe - not necessarily organic, but safe - without the excessive use of pesticides, for example, that would prove a real resolution of the food safety issue," he said.

Li Xinzhu contributed. Write to the reporter at wuwencong@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 12/29/2011 page1)