Organic labeling can be food for thought

Updated: 2011-12-29 07:50

By Wu Wencong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Wang Xiaoying / China Daily |

Recipe for confusion as status is hard to define and controversial, Wu Wencong reports in Beijing.

The Beijing Organic Farmers Fair is reaping a harvest of popularity. Followers of its micro blog at sina.com grew to almost 22,000 in less than a year. The fair, held monthly last year, is now a weekly attraction.

Moreover, the location has shifted from the suburban Changping district to centers such as the capital's swanky Sanlitun area.

There is just one problem. Despite the fair bearing an "organic" stamp, few of the farmers participating have actually received any certification confirming organic status.

"How can you claim your products are organic when you don't have the certificate?" asked Sun Dewei, who runs a small farm in Shunyi district.

Sun said his farm operates in a way that's as close as possible to, but is still not completely, organic. "Whether it (the certificate) really works or not, it is the only legal way in China to carry the organic label," he said.

A number of food safety cases have erupted recently. As a result, consumers, especially the middle class who can afford and are willing to pay higher prices for healthier food, are enthusiastically chasing organic products because they believe them to be safer and healthier.

However, insiders and experts say that being safe is simply the bottom line for organic food. In China, not only is the term "organic" being abused, but the part it can play in promoting food security has also been overestimated as a result of the high-end nature of the food and the disorganized nature of the industry.

Abuse of concept

Sun refers to his farm as "continuous" rather than "organic", saying that "organic" should be used sparingly and only then with authorization. "They (the farmers at the fair) think the certification system for organic food is lame, yet they themselves are using the term to lure consumers, who lack basic knowledge about organic food."

Sun, who has been running his farm for 10 years, said "organic food" means much more than just produce that has been grown without chemical fertilizers and pesticides. He said there are other technical criteria, such as the use of seeds without a chemical coating to help growth.

Another is an isolation belt of a certain width, within which crops such as corn are planted to prevent contamination from outside chemicals but which will be abandoned later, not sold.

"This criterion alone shuts the door on the term 'organic' for many small farms around Beijing," Sun said. "The land they have is already limited enough for planting produce, so how can they shoulder the cost of growing hectares of crops that they can't sell later?"

He suggested that fairs such as the one in Beijing could use labels such as "safe products" or "natural", instead of "organic". Meanwhile, there have been complaints about products sold at the fair that are not fertilizer-free.

Luzhimeng, which translates to Green Union, is a small shop in Beijing's Changping district that was among the first retailers to join the Beijing Organic Farmers' Market when it started last year. In October the owner decided to quit.

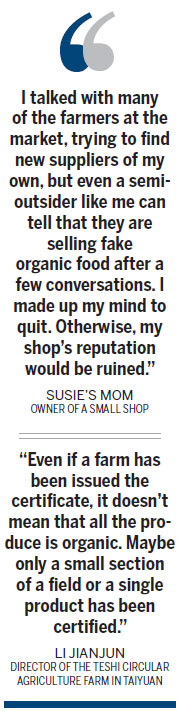

"I talked with many of the farmers at the market, trying to find new suppliers of my own, but even a semi-outsider like me can tell that they are selling fake organic food after a few conversations," said the owner, a 36-year-old former housewife who prefers to be called Susie's mom. "So I made up my mind to quit. Otherwise, my shop's reputation would be ruined."

The shop sells safe and organic food, mainly in its own neighborhood, and was launched by six mothers who wanted their children to have safe food.