Path to transition won't be an easy one

Updated: 2013-08-05 07:18

By Ed Zhang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Premier Li Keqiang has acknowledged that while he can tolerate slower growth, at least some capital investment is needed to prevent it from becoming too slow.

Two checks were signed late last month, one for modernizing the rail system in central-western China, and the other for investment in pollution controls in Chinese cities. The Chinese called them micro-stimulus.

This is a more targeted, more restrained kind of stimulus. It is small compared with the stimulus of 2008-09, which cost 4 trillion yuan ($590 billion based on the exchange rate at the time), but was followed by much more in spending projects initiated by local governments.

Since the new cabinet took office in mid-March it has shown no enthusiasm for a stimulus program of the 2008-09 kind. That is why one key component of so-called Likonomics is said to be no stimulus (the other two components being deleveraging and structural reform).

But on the practical side, "no stimulus" cannot be understood in the bookish way. Even though economists are right in saying that China's change of development model - from one driven largely by capital investment to one driven largely by domestic consumer spending - is long overdue, ultimately an economy is not simply a machine whose operation can be changed at the flick of a switch.

Nevertheless, a comprehensive change in the economy and the way it is managed is long overdue and has public backing, but it will take time to produce results.

This was how Deng Xiaoping managed reform in the early stages. The first attempt to abolish people's communes took place in the winter of 1978, at the hands of farmers in highly impoverished pockets of the country.

Then pilot projects quietly spread from one place to another, and rising output of farm output over the next couple of years proved that they were feasible. Nationwide, the people's commune system was not officially abolished until 1981, when the new system, allowing farmers more freedom to manage family plots and cottage businesses, was showing undoubted success.

If the transition of the economic model in the 1980s took at least three years, the present transition is likely to take a lot longer. In those days there was a ready replacement, because farmers knew how to manage a family plot but today a ready replacement is still not at hand. The more desirable new model still remains a skeletal theory that needs to be fleshed out by those who are to make the transition.

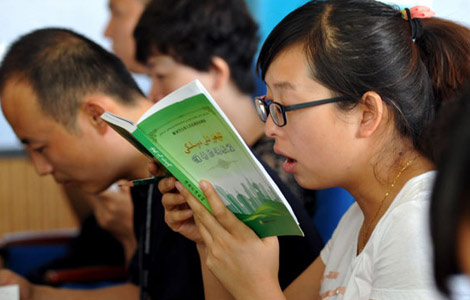

Many questions remain unanswered, such as how to create new jobs without building new factories and relying on private efforts in various services. Another is how to improve living standards by giving people more equal opportunities, decent services, free time and amenities, in addition to rising wages and financial support. Providing the answers to these questions will entail intensive learning.

Meanwhile, there is still room for the traditional type of development, such as building roads, railways and houses. China is a large, developing country. Its need for physical infrastructure is still undeniable.

The really hard part in all of this is how to implement the transition in a steady way - including gradually reducing the dependency on capital investment. To do so, Beijing will have to release some micro-stimulus, designed for particularly worthy projects, while strictly controlling government spending and cracking down on waste.

The author is editor-at-large of China Daily.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China's obesity rate on the increase

Washington Post sold to Amazon's founder

Fonterra says sorry for 'anxiety'

Detroit Symphony brings China to NYC

Service sector drives up growth

Globalization of Chinese culture becomes hot topic

Huawei expands in London

Web 'answer to export woes'

US Weekly

|

|