Children take a walk on nature's wild side

Updated: 2011-09-14 07:59

By Zhang Yuchen (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

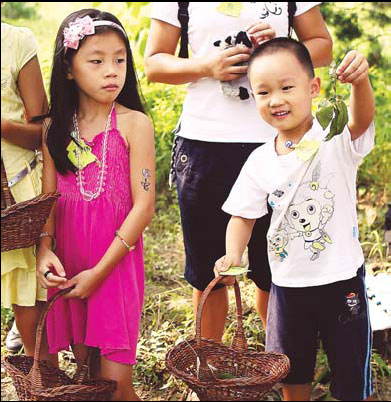

Liu Zhengtang and Annie collect leaves at Beijing's Olympic Forest Park on Aug 28 as they take part in "Looking for Autumn", a program to help children become more familiar with nature. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

The NGOs Friends of Nature and Beijing Brooks Education Center organize activities to help children bond with nature at Beijing's Olympic Forest Park on Aug 29. Experts fear that future work to protect the environment will be undermined if children do not become familiar with the great outdoors. Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

A girl plays games on an iPod touch in an Apple store in Ningbo, Zhejiang province, on July 10. Zhang Heping / for China Daily |

The great outdoors beckon for young explorers as they venture outside, Zhang Yuchen reports in Beijing.

Liu Zhengtang slowly approached a patch of grass as if he were a pioneer exploring a new world, curious and cautious.

It was the first time the 5-year-old had ventured into the woods.

Looking briefly at the ground, he bent down to pick up a fallen leaf, long and narrow in shape, near a row of underbrush. He then gingerly placed it into a little bamboo basket chosen especially for holding the "precious collection" he planned to obtain on his scavenging trip.

Liu and his family were taking part, along with others, in "Looking for Autumn", a program meant to help children become more familiar, or in some cases, acquainted with the great outdoors.

The program, which took Liu to the woods at Beijing's Olympic Forest Park, was designed in accordance with recommendations made in a book called I Love Dirt!: 52 Activities to Help You and Your Kids Discover the Wonders of Nature.

The boy's father, Liu Yingbo, said the opportunity to explore nature was welcome. He said his family lives near Purple Bamboo Park in Beijing but still finds little time to spend outdoors.

"Even in a park, my son's attention is easily drawn to electronic games rather than to bamboo or other green plants," said Liu Yingbo, who works as an information-technology engineer.

Rather than taking his son into the woods, he said he often finds himself paying 20 yuan ($3) or so to give him two or three minutes of entertainment on amusement-park rides.

Liu Yingbo's childhood was quite different. Born in 1981 in a rural part of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, he grew up looking upon the woods and fields as his playgrounds.

Formative experience

After the trip to Olympic Forest Park in late August, Liu Yingbo said his son had just undergone what will prove to be one of the most important encounters in his life: a first brush with the woods.

"We never found a good time to take him out and let him play in nature," said the father. "I feel very sorry for my son because he is ignorant of the outdoors."

At the park, the boy took instructions from an environmental trainer from Friends of Nature, one of the first environmental NGOs established in China. The trainer asked him to look for evidence that autumn was approaching. Shortly afterward, Liu trekked back on a footpath smiling proudly to his mother, who stood ready to help him.

He picked up a green pen and took a moment to draw the leaf he had collected, using his mother's back as his drafting table. The morning sunshine cast beams of gold onto his side.

Different childhood

"When I took him back to my hometown in Inner Mongolia, he showed that he knew nothing about the natural things I knew about when I was a little boy," Liu said.

Growing up mainly indoors, Liu Zhengtang's favorite form of entertainment came in playing games on his father's cell phone and iPad.

"He would open my iPad immediately when he went back home," the father said "He plays video games very well, and his mother and I have to place limits on the amount of time he can spend on them.

"It is a real pity that this generation always learns at a very early age to look to video games for enjoyment instead of to nature."

Why, though, is it so important that a person be familiar with the great outdoors?

Some experts say that a life spent mostly inside not only deprives a person of many joys but is not likely to be healthy. There is evidence to support that assertion.

In 2010, Chinese children between the ages of 3 and 6 performed worse on tests used to gauge how far they can jump and throw things, according to the State General Administration of Sport's third national condition survey, released this year. The same study, which culled data from 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions on the mainland, suggested that the health of teenagers in general has also declined in the past 20 years.

"More than just lacking a chance to run or play in outdoors, children, we find, are very estranged from the environment," said Hu Huizhe, director of the Friends of Nature's environmental education department.

Others fear the distant feelings will have long-lasting consequences.

"Their detachment from nature will not only harm them but also will threaten to undermine future work to protect the environment," said Huang Yu, a lecturer at Beijing Normal University's school of geography, who began to take part in environmental education programs in the late 1990s.

Other families find themselves contending with the same issues. In late August, Lin Yinjie took her two young daughters into the woods for the first time since they had settled down in Beijing a few years ago.

The girls were then attending an elementary school affiliated with Peking University, where the school's curriculum prescribed that they take outdoor exercise once a quarter. Lin at times would also bring them on weekends to a nearby park that had a large lawn and an artificial lake.

"That place is good but I can't help noticing that people are asked to stay away from grassy areas in Chinese cities," Lin said. "That confused me, especially when I wanted my girls to play freely outdoors."

Roots of alienation

In China, a rapid pace of urban construction and the consequent loss of unaltered places in nature has contributed greatly to city dwellers' estrangement from the great outdoors.

By 2003, a third of all grasslands in China had been degraded in some way and a fifth of the wild animals and plants in the country were endangered.

"Cities are becoming more and more separate from the natural world," Hu said. "It is getting harder and harder to restore a sense of there being a cooperative relationship between nature and human beings."

Experts concede they lack statistics or reports showing the effect of the public's increasing alienation from nature but believe it can hardly be good.

"Some children who lead 'caged in' lives in their homes in cities, surrounded by man-made things, are probably more prone to diseases, disorders or depression," said Mu Danfeng, the environmental education instructor for Friends of Nature. "As soon as they step out into the natural world, they can quickly recover."

She said taking part in simple outdoor games can prove a powerful remedy. Just take, for example, what can be done with playing with mud, Mu said.

Mud, she pointed out, can be formed in all sorts of ways to produce various shapes. A child who is asked to make something recognizable out of it must make use of several of his senses and freely exercise his imagination to accomplish that task.

Toy robots, in contrast, usually can only be played with in a few predetermined ways, robbing children of a chance to put their native ingenuity into practice, Hu said.

"Nature benefits children as well as adults by reducing the stress they feel and giving them a greater sense of joy," Hu said.

Not everyone appreciates that. Every year, about 1,500 school children visit the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Xishuangbanna tropical botanical garden, the largest botanical garden in China.

"Most parents and group organizers take a narrow view of nature studies," said Wang Ximin, the director of the garden's public science education department. "They always tend to abstract knowledge from the whole process and pay little attention to how the students feel or how they touch things in nature."

Study regimen

Hu said environmental education, in general, should proceed according to this sequence:

First, students should be taught in the classroom about the environment mankind lives in. What they learn in this stage will be imparted to them through the use of conventional teaching methods.

Second, they should be taught in the environment. This stage will be the most different from more common forms of instruction, such as how math is taught in classrooms. It requires students to go out and see the great outdoors for themselves, enabling them to gain a better understanding of a woods or other natural object than they can in any other way.

Finally, they should be taught to do work for the environment. The aims of this stage are to define the proper relationship between human beings and nature and to ensure that people act in a way that won't upset that relationship. This stage is meant to result in a change in behavior.

Yet, no matter how well students are taught, environmental advocates can't expect these changes in attitude to come about immediately, Wang said. "If we give up on imparting knowledge about nature to these children, they may not show any love for the environment when they grow up."

"The less time they spend outdoors, the less they will be fond of the outdoors," Mu said. "How can we expect a person with no relationship to a particular lake to care about whether it is polluted? "

A 2009 survey sponsored by the US-based Nature Conservancy showed that a person who has spent time hiking or backpacking is more likely to give money to environmental organizations 11 to 12 years in the future.

The push to have children go outdoors to learn about nature by no means contradicts what is happening in conventional instruction. In the past, many schools and other educational organizations had imparted subject matter using indoor lectures or slides shows.

The central government, though, began to call for a divergence from that system as early as the 1970s, even before concerns about children's lack of familiarity with nature began to become prevalent.

In 2003, primary and middle schools first listed nature studies as part of their curricula, according to the Ministry of Education's environmental education implementation guide that was released the same year.

The guide calls for all students to be given a means to know nature better. Primary school students, it says, should start on that path by watching stars in the night sky or reading beautiful prose about rivers or woods. Students in higher grades are meanwhile to dive into environmental research by learning about recycling rates in their neighborhoods and gathering similar information.

"They (the government) have a great plan," Huang said. "The trouble is that there is no enforcement of it. The way the plan is being put into effect is just too lax."

Experts said some might consider nature studies to be insignificant because it is a subject that overlaps many others and that has no specific curriculum.

Huang said 21 nature study centers in universities across the country and about 100 professors are working to improve the ways nature studies are taught.

And about 2,000 teachers or principals in 100 elementary or middle schools are being trained to give classes in nature studies.

"We can see the whole teaching staff is becoming more aware and accepting," Hu said. "But teaching the subject effectively and helping children bond with the natural world draws on teachers' abilities, which need to be honed by more professional training. Some teachers who are good indoors may not be qualified to teach about the environment."