Bridge to more respect

Updated: 2011-11-18 07:58

By Shao Wei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

GONGLIU, Xinjiang - Cracks appeared in the walls of Inayat Sillam's two-bedroom bungalow just seconds after the magnitude-6 earthquake that struck northern Xinjiang on Nov 1.

The first thing the 81-year-old Uygur man did was not soothe the fears of his family but rush out to check whether the only bridge in the village was still standing.

|

|

|

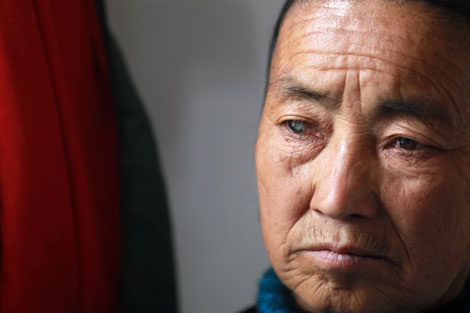

Inayat Sillam is a Uygur resident in Moyinguze village in Xinjinag. |

"This bridge is the most valuable treasure for me. I felt released after seeing it survive," Inayat told China Daily, pointing to a cement bridge behind his house.

He has spent 35 years, at his own expense, building and maintaining the bridge.

"Since 1976, I've built five bridges in the same place. The other ones were made of wood, which were washed away by the river," Inayat recalled.

The village of Moyinguze - a poor village with the largest population in Gongliu county of Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region - was one of the areas hardest-hit by the earthquake, with more than 90 percent of the houses collapsed and damaged.

The current bridge is by far the most expensive and the strongest, made of cement and a second-hand truck beam, he said.

Meanwhile, the four members of his family, who rely on a cornfield one-third of a hectare in size, can't make ends meet.

In his small, beat-up bungalow, a small television is the only electrical appliance, but "it has been broken for a long time", according to his wife, Tunishkez.

The family only earns about 5,000 yuan ($787) a year from the cornfield, and Inayat receives a minimum living subsidy of 430 yuan every quarter from the government.

"He sold two cows and three sheep to collect 8,000 yuan for building the cement bridge in 2008. I quarreled with him several times, but couldn't change his mind," Tunishkez said with a helpless smile. While complaining, the woman was preparing lunch for the family: cold naan bread and a vegetable dish with a little mutton fat.

"We seldom have meat. The mutton is for the Corban Festival (a major Islamic festival showing faith and obedience to Allah)," she said. "Whenever we had some savings, my husband will use them for the bridge. I'm already used to it."

Inayat's stubbornness comes from his kindness to fellow villagers.

The village, which has a population of about 8,000, mostly Uygurs, ploughed a two-meter-wide canal for farm irrigation in 1975. But the canal cut off the road to the primary school and the bazaar in the village.

"There are a total of 1,200 pupils in the school. They had to detour more than four km a day on their way to school. So I decided to build a bridge," he recalled.

Those living in the village were skeptical at what he did, until they walked across the bridge every day and realized that Inayat's "silly deeds" were meant to bring convenience to people.

Yakupujan recalled when Inayat built the first bridge.

"Uncle Inayat cut down 10 trees and spent five days building the bridge. We watched his 'silly activities' and no one offered him a hand. I feel regretful now," he said.

Inayat said he enjoys watching people and vehicles passing on the bridge.

"The bridge has become the key link to the school and nearby mountains. Lots of students and herders walk on it and say 'Thank you' to me. This makes all my efforts so worthwhile," he said.

Every morning, Inayat cleans the floor of the bridge and reminds students to keep away from the railings.

"These railings are low. I plan to save some money next year, and heighten the railings and post a notice to guarantee the students' safety," he said.

"I'd been called 'a bad guy' for nearly 10 years during the 'cultural revolution' (1966-1976), because my parents were landlords. But since I built the bridge, my life has changed. People treat me well and regard me as 'a good guy'. I'm quite satisfied with this," he said.